Philippe de Montebello holding the Madonna and Child, c. 12901300, by Duccio di Buoninsegna (2004.442), bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2004.

Contents

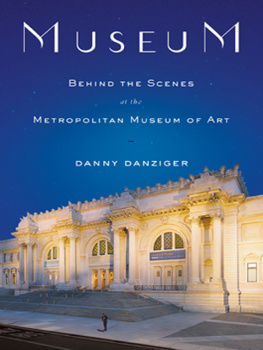

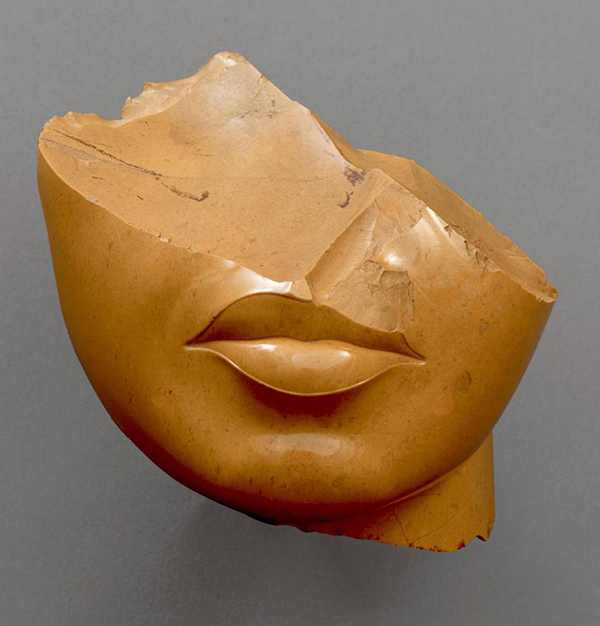

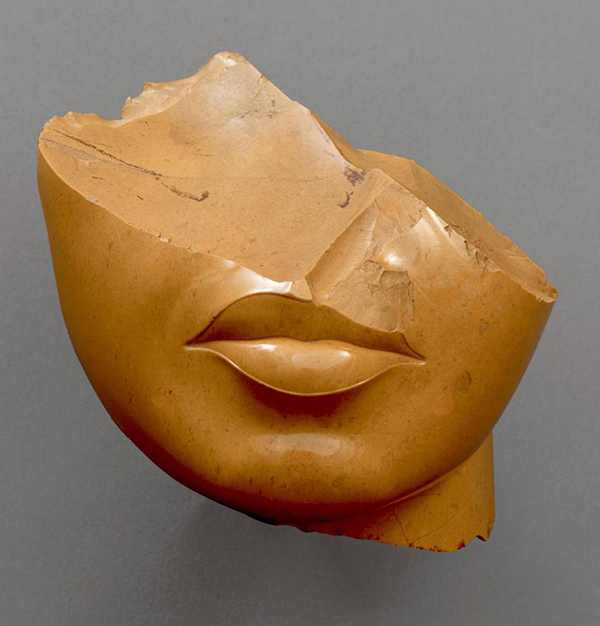

Philippe de Montebello pauses in front of a piece of shattered yellow stone. This, he exclaims, is one of the greatest works of art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, indeed in the world, of any civilization! The object we are looking at is part of a face, the lower section. Of the upper portions the brow, the nose, the eyes nothing remains.

Those sheared off long ago, in one of the innumerable accidents that occurred during the approximately 3,500 years since the sculptor finished carving it. What is left is just the chin, fractions of cheek and neck, and the mouth. Essentially, the sculpture is a pair of lips as full and sensual as those of Mae West, which were once recycled by Salvador Dal in the form of a surrealist sofa. In its way it is every bit as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa; there is no smile, only an expression of the mouth, as if the lips were about to part.

This splintered remnant portrays the face of an Egyptian woman who lived in a palace on the Middle Nile in the 14th century BC. She might have been Nefertiti, or she might not. We do not know, and it is extraordinarily unlikely that anyone will ever find out. The only way would be to discover the rest of the carving, broken and discarded probably thousands of years ago.

Fragment of a Queens Face, New Kingdom Period, Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, c. 13531336 BC, Middle Egypt, probably el-Amarna (Akhetaten), yellow jasper, 13 12.5 12.5 (5 4 4). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926 (26.7.1396). Photograph by Bruce White. Image Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If you told me youd found the top of the head, Philippe continues, Im not sure I would be thrilled because I am so focused, so absorbed and captivated by the perfection of what is there; that my pleasure and it is intense pleasure is marvelling at what my eye sees, not some abstraction that, in a more art historical mode, I might conjure up. Its like a book that you love, and you simply dont want to see the movie. Youve already imagined the hero or the heroine in a certain way. In truth, with the yellow jasper lips, I have never really tried to imagine the missing parts.

The point about the mouth of the anonymous Egyptian queen (or, perhaps, princess), is that it is a fragment. That is its fascination. In a way, however, everything around us in the Met is a fragment: as well as the yellow jasper carving, there are bits of buildings, parts of sculptural ensembles, rooms from houses, and paintings that have been removed from the walls of villas and palaces.

What we see in the Met or any other museum or collection are elements detached from a greater whole. The Egyptian womans lips are part of her face, but they have also been broken off from some context, quite what we do not know, that made sense during the reign of the Pharaoh Akhenaten. And that epoch, with its distinctive styles and beliefs, was only a passing moment in the period of the New Kingdom, which forms a subsection of the long, long history of Egyptian art and civilization, and in turn takes its place in the wider chronicle of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean. So it goes on, like a set of Russian dolls, each fitting into something larger.

MG One day, while I was sitting for a portrait to Lucian Freud, I asked him what, for him, was the most difficult aspect of painting such a picture. His answer was a surprise: that he changed all the time. I just feel so different every day that it is a wonder that any of my pictures ever work out at all. A few days later, it emerged that I the subject constantly altered too. Therefore, his attempt to make an enduring image was also an effort to track two moving targets: artist and model.

What was true of Lucian in 2004 surely applies to some extent to all of art and life. If we stand in front of a work of art twice, at least one party the viewer or the object will be somewhat transformed on the second occasion. Works of art mutate through time, albeit slowly, as they are cleaned or conserved, or as their constituent materials age. Even if they remain visually identical, they may make a different impression according to the company they keep. Next to a Salvador Dal, the Egyptian queen would not seem the same at all.

We, the viewers, however, are yet more fluctuating. Had I not been walking through the Met in Philippes company on that bright autumn day, I would probably not have paused in front of the yellow jasper lips; certainly I would not have seen them as I did, because I looked at them in his company. The next time I saw them would be inflected, together with many other factors, by the memory of the first time. For his part, Philippe had seen this fragment hundreds of times before which doubtless coloured his reaction, as did the fact that on this occasion he was looking at them with me, listening to my reaction to his response. Everything is like that.

Inevitably, we all inhabit a world of dissolving perspectives and ever-shifting views. The present is always moving, so from that vantage point the past constantly changes in appearance. That is on the grand, historical scale; but the same is true of our personal encounters with art, from day to day. You can stand in front of Velzquezs Las Meninas a thousand times, and every time it will be different because you will be altered: tired or full of energy, or dissimilar from your previous self in a multitude of ways.

Philippe and I had embarked on a joint project: to meet in various places as opportunities presented themselves in the course of our travels. Our idea was to make a book that was neither art history nor art criticism but an experiment in shared appreciation. It is, in other words, an attempt to get at not history or theory but the actual experience of looking at art: what it feels like on a particular occasion, which is of course the only way any of us can ever look at anything.

The result is affected by random factors aching backs, closing hours, passing whims as such experiences always are. It is also permeated by an emotion that is generally filtered out of writing on art, or reduced to a clich: love.

The old French word amateur has acquired many meanings. Originally, it signified one who loves something. In modern English it implies non-professional. Both Philippe and I spend our working lives engaged in art in one way or another, but in the original sense we are both amateurs of art: we love it. Igor Stravinsky once wrote that his first destination, on arriving in a new city, was the art gallery. Philippe and I both feel the same: a new collection, an unvisited church, mosque or temple is a thrilling prospect. To see such things is at least half the point of travel and this is, among other things, an unusual variety of travel book.

MG Philippe, can you think of a single moment, a single experience that might have led you to a life in the arts?

PdM Thats the toughest question, Martin, and the one most likely to yield an invention, or a half truth. But since an episode just happens to spring to mind, lets go with it. It was my first love, actually, a woman in a book.

Next page