ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is a pleasure to thank the many people who have helped me finish this book. I am grateful to Leonard Wilson, Lyells biographer; Julian Reid, archivist of Corpus Christi College, Oxford; and Roderick Gordon, executor of the Reverend William Bucklands estate in England. I am also strongly indebted to several scholars working on nineteenth-century science and religion, including Bernard Lightman, Jude V. Nixon, Martin Rudwick, James Secord, and Keith Stewart Thomson. Books by Lance St. John Butler, Jennifer Michael Hecht, and A. N. Wilson were also frequent touchstones. I was fortunate indeed in the external readers whom Yale asked to evaluate the manuscript, and I greatly appreciate their expert advice.

I owe a debt of thanks to Holly Clayson and Northwestern Universitys Humanities Institute for giving me a well-timed fellowship to work on the manuscript and to the dean of Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences for a sabbatical leave to complete it. Many thanks also to my colleagues in the English Department at Northwestern, especially fellow Victorianists Chris Herbert, Jules Law, and Tracy Davis. Wendy Wall and Susan Manning, former were presented respectively at Northwesterns Humanities Institute; as a plenary at the British Association for Victorian Studies conference at the University of Leicester; and as the 2007 Josephine Ferguson Lecture in the English Department at Tulane University. Thanks especially to Gowan Dawson, Molly Rothenberg, and Gaurav Desai for arranging these visits.

Emma Butterfield, a picture librarian at the National Portrait Gallery, London, dealt with a stream of requests with patience and humor. Thanks also to Paul Cox, assistant curator of the gallerys archives and library, for helping me hunt down the owners of several other images. I owe a debt of similar thanks to Auste Mickunaite at the British Library; Daragh Kenny at the National Gallery, London; and to Frances Gandy and Hannah Westall at Girton College, Cambridge. I am grateful to Lybi Ma and the team at Psychology Today for their ongoing support. Peter Robertson, editor of the International Literary Quarterly, let me reproduce several paragraphs from my essay On Literalism, issue 5 (November 2008).

Wendy Strothman, Lauren MacLeod, and Dan OConnell at the Strothman Agency in Boston have been wonderful interlocutors. Its also been a pleasure to work again with Jean Black, my editor at Yale. Sincere thanks to her, to Jaya Chatterjee, her assistant, and to my superb copyeditors Vivian Wheeler and Laura Jones Dooley.

My biggest debt is to Jorge Arce and to our families and friends in England, the States, and Per. I dedicate this book to him, and to them, with great pleasure, deep thanks, and, pues, sin dudawithout doubt.

ONE

Miracles and Skeptics

The roots of Victorian doubt take us far into the eighteenth century, when scientists and philosophers began openly to question biblical accounts of the Earths creation. Geologists studying cliffs and ravines publicly doubted whether a single flood could have covered the entire planet, much less whether one man and his family could have rescued every species of animal on Earth from it. Philosophers, too, openly challenged the idea of the miraculous. In doing so, they also cast doubt on the truth and reliability of the Gospels and Old Testament.

In 1781, after both lines of inquiry crossed, rattling the Established Church, an anonymous pamphlet appeared bearing the startling title, The Doubts of Infidels; or, Queries Relative to Scriptural Inconsistencies and Contradictions. The author called himself A Weak but Sincere Christian who was submitting his questions to The Bench of Bishops for Elucidation. As a self-described infidel, however, the author captured both the words flavor of heresy and its suggestion of infidelity (infidel comes to us via the Old French infidle).about scriptural inconsistency, which he detailed for them chapter and verse.

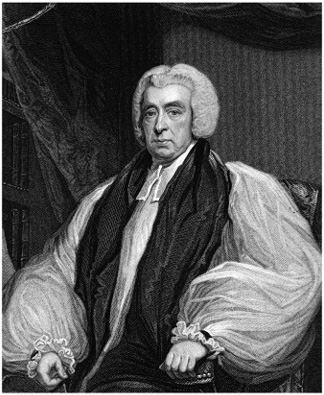

The pamphlet has been attributed to William Nicholson, a renowned London chemist and philosopher, and its anger is best understood as responding to an act of Parliament passed the same year. After the bishop of Chester, Dr. Beilby Porteus, rallied in 1780 to stop freethinkers and doubters from meeting on Sundays, he helped to create a new law called An Act for Preventing Certain Abuses and Profanations on the Lords Day, Called Sunday. The law wasnt amended until 1932, when the Sunday Entertainment Act began to chip away at its broad powers, and it had a significant effect on British culture and society in the decades in-between. Public institutions such as museums, art galleries, libraries, and public gardens were required to stay closed on Sundays. Even public lectures were banned on such days. As the free-thinking philosopher John Stuart Mill later complained in his influential treatise On Liberty (1859), the act also encouraged repeated attempts to stop railway travelling on Sundays. What one sees in such attempts, he complained, is a form of religious bigot[ry] and persecution: The notion that it is one mans duty that another should be religious, a belief that God not only abominates the act of the misbeliever, but will not hold us guiltless if we leave him unmolested.

The 1781 act seemingly began with more limited powers, but they were easily misinterpreted. The law authorized the government to fineeven to imprisonlandlords and proprietors who allowed public entertainment or amusement upon the evening of the Lords Day. According to the bishop, the chief concern was this: groups were meeting under pretence of inquiring into religious doctrines, and explaining texts of holy Scripture when they were unlearned and incompetent to explain the same.

If that sounds over the top, even a fraction paranoid, consider that Bishop Porteus, an avid reformer and abolitionist, with interests also in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, had sought the aid of Parliament to crack down on religious criticism in Britain. In the bishops own words, which his biographer uncovered a few years later, The beginning of the winter of 1780 was distinguished by the rise of a new species of dissipation and profaneness.

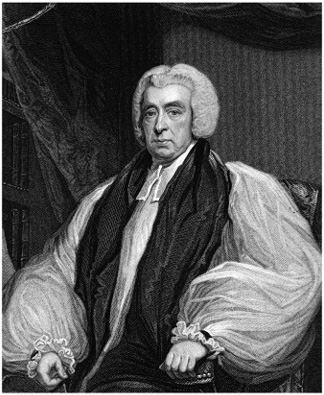

Figure 1. Henry Meyer, portrait of the Right Reverend Beilby Porteus, bishop of London, 1834, stipple engraving after a 1787 portrait by John Hoppner. National Portrait Gallery, London.

On Sundays, the bishop noted with dismay, groups across London would assemble in public meeting rooms, using names such as Christian Societies, Religious Societies, [and] Theological Societies (LBP, 72). The professed design of the former, writes the man later appointed bishop of the capital, was merely to walk about and converse ; but the real consequence, and probably the real purpose of it, was to draw together dissolute people of both sexes [for] the amusement [of] discuss[ing] passages of Scripture (72-73; emphasis in original).

The bishop insisted that these meetings gave offence to everyman of gravity and seriousness , several of whom I have heard speak of it with abhorrence. Foreigners apparently had been shocked and scandalized considering it a disgrace to any Christian country to tolerate so gross an insult on all decency and good order (LBP, 72-73).

Anyone wondering what Bishop Porteus meant by good order should recall that, just a few decades earlier, Robert Walpoles regime had closed theaters it deemed critical of the Crown and Parliament. Nor was it easy to voice even mild doubt about Christianity.

In June 1780, just months before the bishop inveighed about moral decay, riots broke out in London after a huge crowd, numbering between forty and sixty thousand, marched to Parliament to protest the repeal of anti-Catholic legislation. Among other things, the laws had prevented Catholics from serving in Britains military, a deficit felt strongly at the time, with the American colonies five years into a war of independence and war looming against France. Led by Lord George Gordon, head of the Protestant Association, the crowd descended on Westminster with banners warning No Popery and statements of concern that Catholics might band with Britains European enemies rather than support their own army.