LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

The Dead Sea Scrolls

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

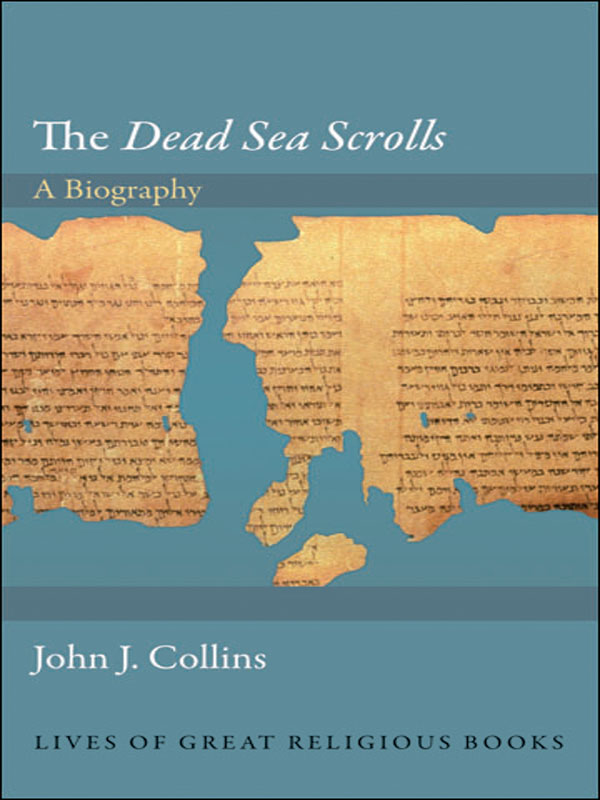

The Dead Sea Scrolls, John J. Collins

The Book of Mormon, Paul C. Gutjahr

The Book of Genesis, Ronald S. Hendel

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Dietrich Bonhoeffers Letters and Papers from Prison, Martin E. Marty

The I Ching, Richard J. Smith

Augustines Confessions, Garry Wills

FORTHCOMING

The Book of Exodus, Jan Assmann

Confuciuss Analects, Annping Chin and Jonathan D. Spence

The Bhagavad Gita, Richard H. Davis

Josephuss Jewish War, Martin Goodman

John Calvins Institutes of the Christian Religion, Bruce Gordon

The Book of Common Prayer, Alan Jacobs

The Book of Job, Mark Larrimore

The Lotus Sutra, Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Dantes Divine Comedy, Joseph Luzzi

C. S. Lewiss Mere Christianity, George Marsden

Thomas Aquinass Summa Theologiae, Bernard McGinn

The Greatest Translations of All Time: The Septuagint and the Vulgate, Jack Miles

The Passover Haggadah, Vanessa Ochs

The Song of Songs, Ilana Pardes

Rumis Masnavi, Omid Safi

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, David Gordon White

The Dead Sea Scrolls

A BIOGRAPHY

John J. Collins

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

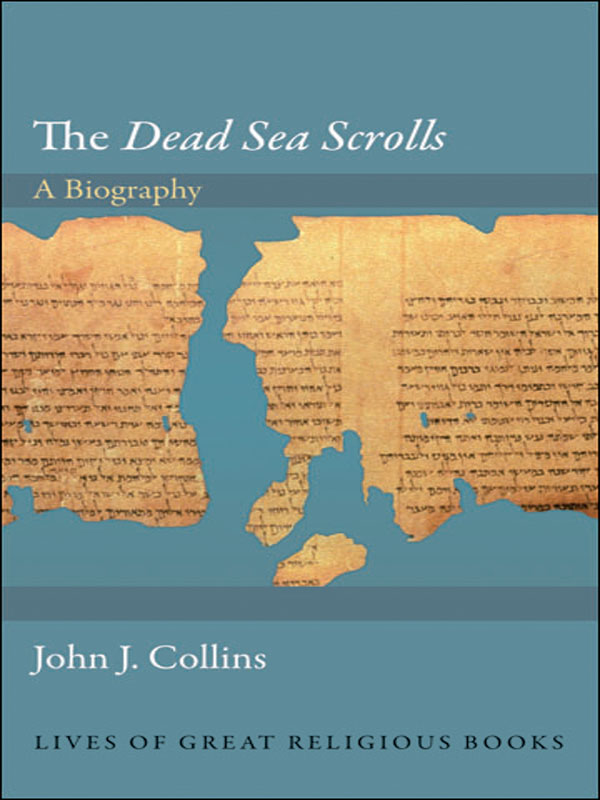

Jacket photograph: The Dead Sea ScrollsFragments of the War of the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness. Scroll found in Qumran Cave No. 1, Israel. Photograph by Z. Radovan / Bible Land Pictures.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Collins, John Joseph, 1946

The Dead Sea scrolls : a biography / John J. Collins.

pages cm (Lives of great religious books)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14367-5 (hardcover)

1. Dead Sea scrolls. I. Title.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The Dead Sea Scrolls may seem to be an unlikely candidate for inclusion in a series on biographies of books.

The Scrolls are not in fact one book, but a miscellaneous collection of writings retrieved from caves near Qumran, at the northwest corner of the Dead Sea, between the years 1947 and 1956. In all, fragments of some nine hundred manuscripts were found. They are written mostly in Hebrew, with some in Aramaic and a small number in Greek. They date from the last two centuries BCE and the first century CE.

The collection is not entirely random, and much, though not all, of it seems to reflect the thought of a Jewish sect, usually identified as the Essenes, around the turn of the era. But the degree of coherence is controversial. While the Scrolls are often presumed to be the remnants of the library of a community that lived at the site of Qumran, this view seems increasingly unlikely. It is more likely that they were brought from several sectarian communities and hidden in the caves in the wilderness at the time of the Jewish Revolt against Rome (6670 CE), although some presumably belonged to the community at the site. Unlike the Bible, which is also a collection of writings of diverse origin, the Scrolls were never known to constitute a distinct corpus in antiquity. Only after their accidental discovery in the middle of the twentieth century CE did the Scrolls become a corpus, or an entity that might be considered an appropriate subject for a biography.

Moreover, the biography of these Scrolls is somewhat like that of Rip van Winkle. While other texts from antiquity influenced the Renaissance or the Reformation, the Scrolls just slept. What we have witnessed in the last sixty-five years or so is not so much a biography as a post-resurrection afterlife, separated from the original environment of the Scrolls by an interval of two millennia.

Nonetheless, the Scrolls now exist as a distinct corpus, with a life of its own. That life has several dimensions. The Scrolls are a scholarly resource, studied intensively by an expanding community of scholars, and of interest not only to historians of Judaism and Christianity but also to sociologists of religion and even philosophers. They are also a tourist attraction, in Jerusalem as well as in museum exhibitions throughout the Western world. Hundreds of thousands of people have waited patiently to catch a glimpse of selected illegible fragments in dimly lighted display cases and come away feeling that they have touched the past. In October 2011, when the Israel Museum launched a website featuring high-resolution photographs of five important Scrolls, the site got more than a million hits in the first week. Only a fraction of the people visiting the site are likely to have been scholars who could read the texts from the photographs. The Scrolls are fodder for the popular demand for mysteriesexotic, dimly understood lore that is paraded to stimulate curiosity in tabloid newspapers and television shows such as Mysteries of the Bible. They are also sometimes a political symboltestimony to the antiquity of Jewish roots in the land west of the Jordan, or conversely of modern Israeli expropriation of artifacts that were discovered in territory that was then under Jordanian control and whose ownership remains in dispute.

The Scrolls have been described as the greatest archeological discovery of the twentieth century. They have certainly been the most controversial.

The Scrolls attract popular interest, and also spark controversy, because they are primary documents from ancient Judea, from around the time of Jesus. Prior to the discovery of the Scrolls there were scarcely any Hebrew or Aramaic texts extant from that time and place. Inevitably, there has been an expectation, sometimes fevered, that these texts would shed light on Jesus or the movement of his followers. Several claims in this regard, beginning a few years after the discovery of the Scrolls and continuing into the twenty-first century, have been quite sensational, and it is precisely these claims that have attracted the attention of the wider public.

Controversy has been fanned by the fact that many of the fragmentary Scrolls remained unpublished for half a century. This delay has provided fertile ground for conspiracy theories, which were further nourished by the fact that several members of the official editorial team were Catholic priestshence the suggestion that the Scrolls had been withheld from the public by order of the Vatican, because of the fear that they might undermine the historical credibility of Christianity. No serious scholars take such claims seriously, but they continue to stimulate suspicion and curiosity among the amateurs who flock to museum exhibits of the Scrolls.

Almost immediately after their discovery, a consensus developed that the Scrolls belonged to the (Jewish) sect of the Essenes, who had long been regarded as forerunners of Christianity. This consensus has aroused the wrath of dissenters to an extraordinary degree. The passion of the debate can hardly be explained by the ambiguities of the evidence. The same is true of the interpretation of the site of Qumran as an Essene settlement. At stake is the relevance of the Scrolls for mainline Jewish tradition, or the degree to which they should be taken to reflect a marginal form of Judaism, closer to Christianity than to the religion of the rabbis.

Next page