The Story of Christianity: Volume 1

The Story of Christianity: Volume 2

To Catherine

Contents

The dissolution is such, that the souls entrusted to the clergy receive great damage, for we are told that the majority of the clergy are living in open concubinage, and that if our justice intervenes in order to punish them, they revolt and create a scandal, and that they despise our justice to the point that they arm themselves against it.

ISABELLA OF CASTILE, ON NOVEMBER 20 , 1500

A s the fifteenth century came to a close, it was clear that the church was in need of profound reformation, and that many longed for it. The decline and corruption of the papacy was well known. After its residence in Avignon, where it had served as a tool of French interests, the papacy had been further weakened by the Great Schism, which divided Western Europe in its allegiance to twoand even threepopes. At times, the various claimants to the papal see seemed equally unworthy. Then, almost as soon as the schism was healed, the papacy fell into the hands of men who were more moved by the glories of the Renaissance than by the message of the cross. Through war, intrigue, bribery, and licentiousness, these popes sought to restore and even to outdo the glories of ancient Rome. As a result, while most people still believed in the supreme authority of the Roman see, many found it difficult to reconcile their faith in the papacy with their distrust for its actual occupants.

Corruption, however, was not limited to the leadership in Rome. The councils that had been convened as a means to reform and to end the Great Schism were able to end the schism, but not to bring about the needed reformation. Furthermore, even in ending the schism the conciliar movement showed its own flaws, for there were soon two rival councilsjust as before there had been two or even three rival popes, and conciliarism had failed miserably in the task of bringing about the much-needed reform. One of the reasons for such failure was that several of the bishops sitting in the councils were themselves among those who profited from the existing corruption. Thus, while the hopeful conciliarist reformers issued anathemas and decrees against absenteeism, pluralism, and simonythe practice of buying and selling ecclesiastical positionsmany who sat on the councils were guilty of such practices, and were not ready to give them up.

Such corrupt leadership set the tone for most of the lesser clergy and the monastics. While clerical celibacy was the law of the church, there were many who broke it openly; and bishops and local priests alikeand even some popesflaunted their illegitimate children. The ancient monastic discipline was increasingly relaxed as convents and monasteries became centers of leisurely living. Monarchs and the high nobility often provided for their illegitimate offspring by having them named abbots and abbesses, with no regard for their monastic vocation or lack of it. The commitment to learning for which monastic houses had been famous also declined, and the educational requirements for the local clergy fell to practically nil.

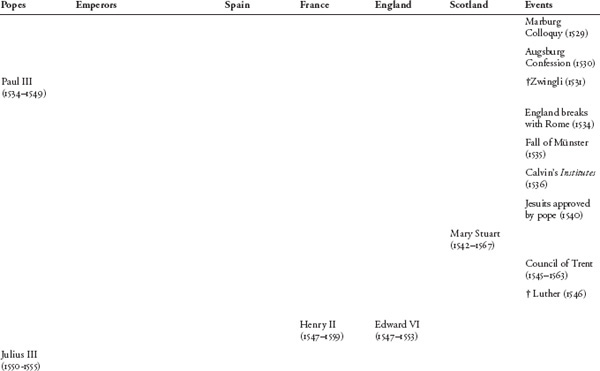

The conciliar movement had waned, and with it also the hope that a general council of the church could produce the much-needed reformation. A sign of this was the Fifth Lateran Council, which was convoked by Pope Julius II, supposedly in order to reform the church, but in truth in an effort to regain the political control the papacy had been losing. The council convened in 1512, and by the time it disbanded in 1517 it had achieved little beyond decreeing an extraordinary taxation to span the next three yearstheoretically, in order to raise funds for a new crusadereaffirming the authority of the pope in the face of French attempts to limit such authority, and insisting on the power and dignity of bishops and other prelates. It should be noted that the council adjourned in March of 1517, a few months before the beginning of the Protestant Reformation.

In such circumstances, even the many priests and monastics who wished to be faithful to their calling found this to be exceedingly difficult. How could one practice asceticism and contemplation in a monastery that had become a house of leisure and a meeting place for fashionable soires? How could a priest resist corruption in his parish, when he himself had been forced to buy his position? How could the laity trust a sacrament of penance administered by a member of the clergy who seemed to have no sense of the enormity of sin? The religious conscience of Europe was divided within itself, torn between trust in a church that had been its spiritual mother for generations, and the patent failures of that church.

But it was not only at the moral level that the church seemed to be in need of reformation. Some among the more thoughtful Christians were becoming convinced that the teachings of the church had also gone astray. The fall of Constantinople, half a century earlier, had flooded Western Europe, and Italy in particular, with scholars whose views were different from those that were common in the West. The manuscripts these scholars brought with them alerted Western scholars to the many changes and interpolations that had taken place in the copying and recopying of ancient texts. New philosophical outlooks were also introduced. Greek became more commonly known among Western scholars, who could now compare the Greek text of the New Testament with the commonly used Latin Vulgate. From such quarters came the conviction that it was necessary to return to the sources of the Christian faith, and that this would result in a reformation of existing doctrine and practice.

Although most who held such views were by no means radical, their call for a return to the sources tended to confirm the earlier appeals by reformers such as Wycliffe and Huss. The desire for a reformation in the doctrine of the church did not seem so out of place if it were true that such doctrine had changed through the centuries, straying from the New Testament. The many followers of those earlier reformers still had in England, Bohemia, and other areas now felt encouraged by scholarship which, while not agreeing with them on their more radical claims, confirmed their basic tenet: that it was necessary to return to the sources of Christianity, particularly through the study of Scripture.

To this was added the discontent of the masses, which earlier had found expression in apocalyptic movements like the one led by Hans Bhm. The economic conditions of the masses, far from improving, had worsened in the preceding decades. The peasants in particular were increasingly exploited by the landowners. While some monastic houses and church leaders still practiced acts of charity, most of the poor no longer had the sense that the church was their defender. On the contrary, the ostentatiousness of prelates, their power as landowners, and their support of increasing inequality were seen by many as a betrayal of the poor, and eventually as a sign that the Antichrist had gained possession of the church. The ferment brewing in such quarters periodically broke out in peasant revolts, apocalyptic visions, and calls for a new order.

Next page