HOW PLANTS WORK

The science behind the amazing things plants do

LINDA CHALKER-SCOTT

TIMBER PRESS

PORTLAND LONDON

My home landscape.

Copyright 2015 by Linda Chalker-Scott. All rights reserved.

Published in 2015 by Timber Press, Inc.

Photo and illustration credits appear on .

Thanks are offered to those who granted permission for use of photos. While every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders and secure permission for all materials reproduced in this work, we offer apologies for any instances in which this was not possible and for any inadvertent omissions.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Timber Press. Mention of trademark, proprietary product, or vendor does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by the publisher or author and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products or vendors.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527

timberpress.com | 6a Lonsdale Road

London NW6 6RD

timberpress.co.uk |

Text design by Stacy Wakefield Forte

Cover design by Anna Eshelman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chalker-Scott, Linda.

How plants work: the science behind the amazing things plants do/Linda Chalker-Scott.First edition.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-690-5

1. Plant physiology. 2. Gardening. I. Title.

QK711.2.C425 2015

571.2dc23

2014032414

A catalog record for this book is also available from the British Library.

In December 2013, as I was finishing this book, I lost my dad to cancer. He was a structural engineer, and while my intellectual interests led in other directions, I got my passion for discovering how things work from him. This book is dedicated, with much love, to Raymond Lloyd Chalker.

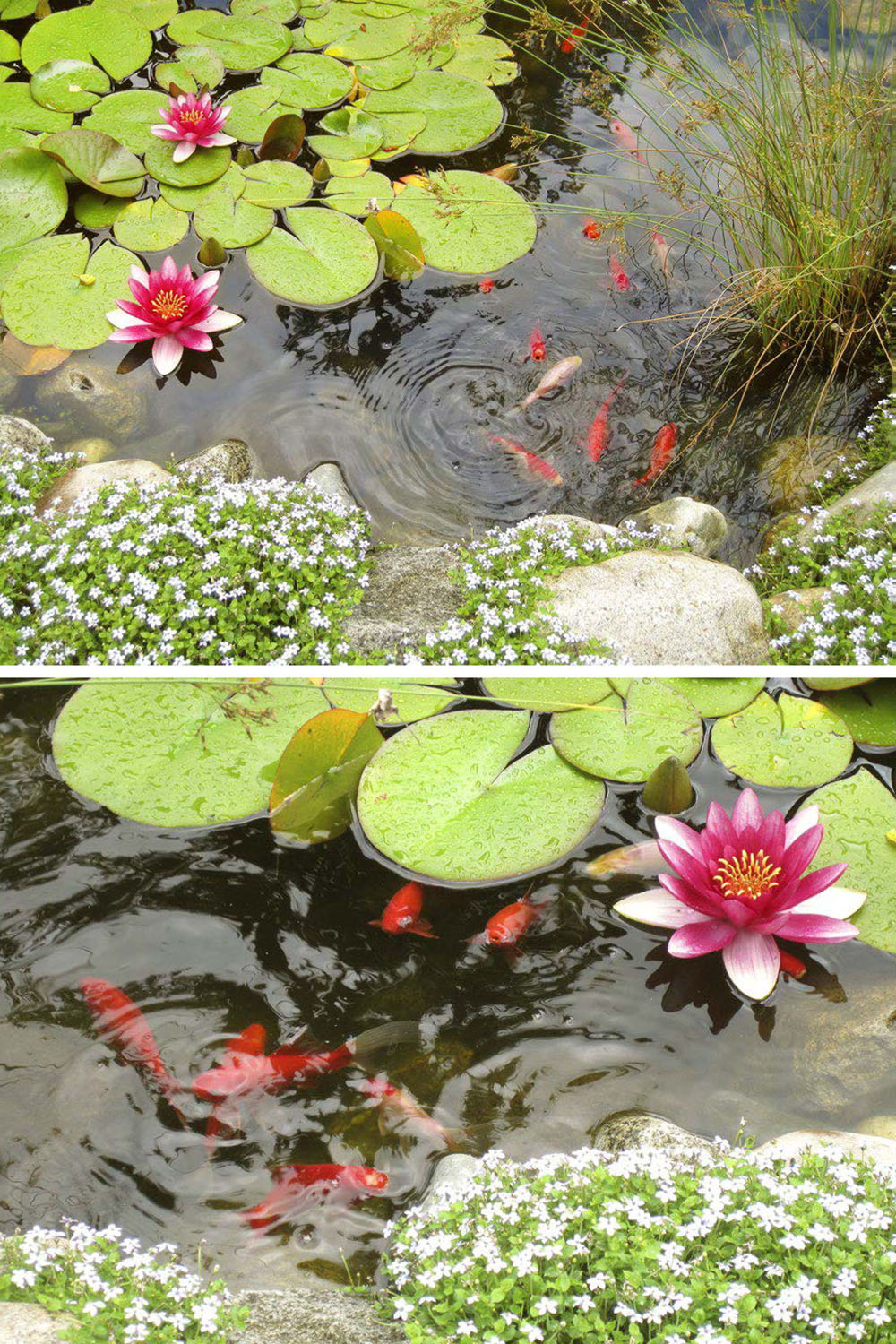

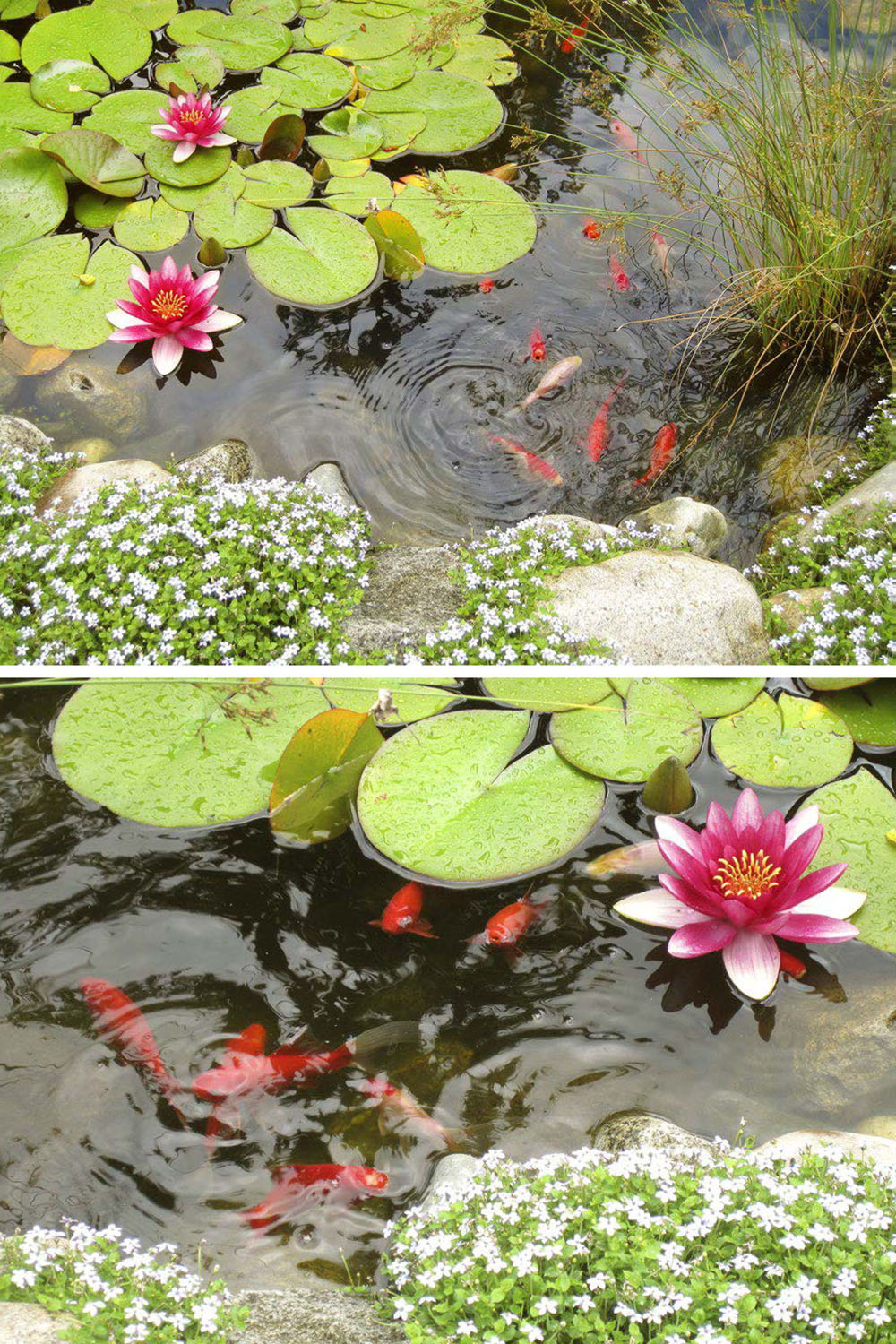

My garden pond.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

From the Ground Up

MY FIRST HOUSE WAS IN CORVALLIS, Oregon, home of Oregon State University, where my husband and I were working on our Ph.D. research in horticulture. Our tiny front yard had enough room for a single specimen tree, in this case a lovely Bloodgood Japanese maple (Acer palmatum var. atropurpureum). We were eager to update the front entry, and we replaced the 1930s era concrete steps with a basket-weave brick entry and wooden deck. The design perfectly showcased our maple, and we were thrilled with the transformation.

Well, until the next year. Suddenly, our maple tree didnt grow so well. Many of the branches died. Finally, it was in such dire straits that we dug it up and replaced it with a much smaller tree, which thrived. But what happened to the first tree?

I asked one of my favorite professors at Oregon State about the sudden demise. Jim Green was our departments extension specialist and didnt teach any of my graduate classes. But he was knowledgeable, easy-going, and had a wicked sense of humor. The graduate students loved him.

Imagine my shock, then, when he turned visibly angry as I explained our landscaping changes and subsequent tree death.

What in the world did you think would happen, he snapped, when you disturbed seventy-five percent of the trees root zone in the middle of summer?

Wow. I hadnt even thought about that. Wed dug up the existing lawn and laid down bricks and deck timbers. I remember silently cursing the roots as we dug. And they were probably cursing us back. I felt stupid, not just because I had irked Jim, but because I hadnt foreseen these consequences myself. After all, I was getting a Ph.D. in horticultural plant physiology!

In hindsight, I think this was a defining moment for me, though I didnt know it at the time. I do know that it was during this time I became more curious as to how plants responded to different environmental stresses (besides dying, of course). Over three decades I evolved from a laboratory plant physiologist (studying how plants function and interact with their environment), to an applied urban horticulturist, and finally to an extension specialist at Washington State University. Though my career continued to change, my interest in how plants work only became more engrossing. I combed through articles on soil science, arboriculture, environmental horticulture, and restoration ecology as well as those in the more traditional botany and horticulture journals.

While botany books describe leaves and roots in isolation from each other (and therefore have chapters called The Leaf or The Root), physiology is the study of systems. Its impossible to explain the physiology of a leaf or a root, because their functions are influenced by other plant parts. It would be like describing how a heart works without mentioning the lungs that provide the oxygen or the arteries and veins that deliver and return blood. Instead, plant physiology textbooks have chapters on photosynthesis, mineral uptake, and flowering. However, it can be difficult to make these conventional topics both accessible and interesting to the nonscientist. Current books on plant physiology are primarily focused on newer research at the molecular and genetic levels. The content is timely and important, but boy does it turn off your average gardener, who probably sees no practical connection between gene regulation in corn and the corn growing in the backyard vegetable garden. What we gardeners most want to know is how plants work so that we can have gardens and landscapes that are healthy, beautiful, and dont need constant additions of fertilizers and pesticides.

So this book is structured a bit differently. Each chapter opens with a real-life situation, often something in my own garden that I invite you to explore with me. Then I integrate the science as needed to answer questions that gardeners invariably have. Ive tried to include all of the practical topics that you would find in a textbook, with examples and illustrations to make the science useful and easily understandable.

Understanding how plants work helps gardeners design and manage landscapes that require less fertilizer and fewer pesticides.

What kinds of things will you discover? We begin at the microscopic level and explore the basic machinery of plant cells, which is substantially different from that of our own cells. Next we explore a vital plant network hidden underground, the root system, which in conjunction with fungal partners seeks out water and nutrients. In .

Many gardeners live in seasonal climates, and our deciduous trees put on a wonderful display of reds, oranges, and yellows in autumn. In , which describes how plants measure day length to determine when its time to germinate, flower, drop their leaves, and close up shop for the winter.

We think of plants as sedentary creatures, but in fact they move quite a bit. In explores how plants respond to pruning, staking, and other forms of manipulation that we try to impose on them. The final chapter investigates every plants ultimate goal: leaving behind offspring to carry their genes forward. Plants produce an amazing array of pigments, fragrances, and seed structures that help them manipulate their environment and pollinatorsincluding gardenersto achieve this goal.