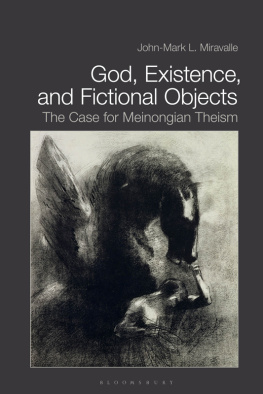

1.1 The Brentano School

In the constellation of Brentanos students who became renowned scholars and philosophers, Alexius Meinong shines as one of the brightest stars. The founder of Gegenstandstheorie , the theory of intended objects, Meinong understood his contributions to metaphysics, philosophical psychology, logic, semantics, epistemology, and value theory, as a systematic continuation of Brentanos Aristotelian empiricism and intentionalist philosophy of mind.

Meinongs philosophy, beginning with a modified version of Brentanos thesis of the intentionality of thought, followed a direction quite different than Brentanos; different, indeed, than that of many others who drew inspiration from Brentanos lectures and writings on philosophical psychology. To situate Meinongs thought in the context of Brentanos school, it is necessary first to sketch his biography, and then to see how he came to philosophy from a nonphilosophical background under Brentanos influence, and quickly emerged as an independent thinker. Despite their later differences, Meinong in his own way elaborated a revisionary Brentanian conception of mind, world, knowledge, and value, together, more importantly, perhaps, with a sense of how philosophical inquiry should be undertaken, which he acquired during his several years of study with Brentano, and which remained throughout his career at the center of his philosophy.

1.2 Biographical Sketch

Meinong was born on 17 July 1853, in Lemberg (Lvov), Poland. His ancestors were German, but his grandfather had immigrated to Austria. At the time of his birth, Meinongs father was serving the Austrian emperor Franz Josef as a senior military officer stationed at the Lemberg garrison. Meinong was related to the royal House of Handschuchsheim, and legally held title as Ritter von (Knight of) Handschuchsheim. In keeping with his republican convictions, Meinong never used this aristocratic form of address.

In 1862, Meinong began his formal education with 6 years of private tutoring in Vienna, followed by another 2 years at the Vienna Academic Gymnasium. Recalling his early schooling, Meinong pays special tribute to his German professor Karl Greistorfer, and his philosophy professor Leopold Konvalina, whom he credits with guiding him toward historical and philosophical pursuits, and away simultaneously from his familys plan that he become a lawyer and his own desire to study music. In 1870, Meinong enrolled in the University of Vienna, where his first major subjects were German philology and history. Later, he concentrated exclusively on history, completing his dissertation in 1874 on Arnold von Brescia, the medieval religious and social reformer. Meinong reports that during this time his interest in philosophy was overshadowed by historical studies. His philosophical appetite was whetted and reawakened only when, in preparation for the philosophical component of a mandatory examination on topics related to his dissertation research (the Nebenrigorosum ), he undertook a self-directed study of Kants [1788] Kritik der praktischen Vernunft ( Critique of Practical Reason ).

To broaden his historical background, and possibly to appease his parents, Meinong entered the University of Vienna law school in the autumn of 1874. There he devoted his time to Carl Mengers lectures on economics, which influenced his later work on value theory. It was just before the 187475 winter term that Meinong decided to turn his attention to philosophy. Brentano had recently joined the philosophical faculty of the University of Vienna, and he and Meinong had met in connection with Meinongs Nebenrigorosum . Significantly, Meinong denies that Brentano directly influenced his decision to study philosophy, but acknowledges that as a result of their encounter he was persuaded that his progress in philosophy would improve under Brentanos direction.

Brentano recommended that Meinong undertake his first systematic investigations in philosophy on Humes empiricist metaphysics. Meinong completed his Habilitationsschrift on Humes nominalism in 1877. This was Meinongs first philosophical publication, appearing as Hume-Studien I in book, Logik .

In , Meinong was appointed Professor Extraordinarius at the University of Graz, receiving promotion to Ordinarius in 1889, where he remained until his death. At Graz, Meinong established the first laboratory for experimental psychology in Austria, which flourished under his directorship until 1914, when, for reasons of failing eyesight, he turned it over to his protg Stephan Witasek. Witasek, in turn, because of failing health, was succeeded almost immediately by Vittorio Benussi. Throughout his long tenure at Graz, Meinong was engaged in difficult philosophical problems, and simultaneously occupied with experimental cognitive and phenomenological investigations, especially those Brentano designated as belonging to descriptive psychology. Here, for the philosophically most active 43 years of his life, Meinong wrote his major philosophical treatises and edited collections of essays on object theory, philosophical psychology, metaphysics, semantics and philosophy of language, theory of evidence, possibility and probability, value theory, and the analysis of emotion, imagination, and abstraction.

By 1904, Meinong, like his teacher Brentano before him, was almost totally blind. The affliction did not strike suddenly, but was preceded by degenerating vision that began to plague Meinong from about the age of 30, when he could no longer read well enough to lecture from written text. The hostilities of World War I brought the wounding of his son Ernst, who lost an eye in combat. This tragedy, and the breakdown of human decency in international relations that affected so many persons of good will at the time, left Meinong deeply dispirited. He died on 27 November 1920, survived by his wife Doris and son.

The Graz school of phenomenological psychology and philosophical semantics centering around Meinong and his students made important advances in all major areas of philosophy and scientific psychology. Meinongs most notable students, who entered the field self-consciously also as Brentanos Enkelschler , prominently include Ernst Mally, Rudolf Ameseder, Witasek, Karl Zindler, Ernst Schwarz, France Veber, Johann Clemens Kreibig, Wilhelm Frankl, Hans Pichler, Eduard Martinak, Hans Benndorf, Fritz Heider, and Benussi.

1.3 Meinongs Apprenticeship to Brentano

When Meinong applied to Brentano for advice about his first systematic philosophical studies, Brentano, as we have seen, recommended that Meinong examine Humes nominalism. The suggestion was significant for several reasons, from Brentanos as well as Meinongs perspective.

Brentano in had just begun his appointment at the University of Vienna, and was already enjoying the prestige of his famous lectures and the appearance of his Psychologie vom empirischen Standpunkt . His proposal that Meinong begin his formal philosophical studies with an analysis of Hume reflects the wisdom of Brentanos well-meaning counsel. Meinongs background in historical scholarship made the choice of an historical topic in philosophy naturally suited to his demonstrated abilities, and one that by virtue of its subject matter would eventually serve as a bridge to more demanding original philosophical inquiry.