Of making many books there is no limit and no end on the earth.

Lo! Scarcely has a great pile of sand the same number.

And as the birds lack number, like the fish in the sea,

so the many books on earth lack number, too.

The greater part of them utter empty talk, useless sentences without substance,

making a display of sonorous words that are nonsense.

Beware lest you are deceived by the cunning fair looks of a book:

for often there is poison hidden under sweet honey.

Swedenborg, from Swedbergs Vngdoms regel och lderdoms spegel (Rule of Youth and Mirror of Old Age, ).

Prologue on a Grain of Sand

Books are grains of sand, countless as the birds of the air and the fish in the sea. Far too many books are written, Emanuel Swedenborg complained. Yet for his own part, he never managed to overcome the rather severe graphomania that haunted him right up to the end. Through time it resulted in a considerable heap of sand. Altogether his writings, translations of them, and books about him have built up an impressive and not inconsequential sandbank in the ocean of knowledge. Being stranded on this sandbank is not without risks. The quicksand of uncertainty and unreliability can give way beneath ones feet, and waves of scrutiny can wash everything out to sea.

Anyone out there on that sandbank, looking around, cannot avoid realizing that metaphorthinking about something through something elseoccurs abundantly in Swedenborgs thought. Books are sand. The world is a machine. The metaphors impelled new thoughts, allowing him to form ideas about the unknown from what is known. That is what this particular grain of sand, this book, will be about; it is a study that seeks to provide a description and understanding, not only of what Swedenborg thought, but also of how he thought as a mechanistic natural philosopher, up to and including 1734. That was the year in which he published two works about the principles of natural things and about the infinite, Principia rerum naturalium and De infinito , in which he espoused a mechanistic world-view that stands out in clear contrast to the organic conception that he embraced in the following ten years and the voyages he began from 1745 into an immaterial spiritual world. The early Swedenborg regarded the world as gigantic machine, everything was machines, everything could be explained as geometry in motion. If Swedenborgs world machine were dismantled into its constituent partsspace, signs, waves, the sphere, the point, the spiral, and infinityone could arrive at a better understanding of how it was designed. It is an investigation that aims to paint the first concerted and complete picture of Swedenborgs early natural philosophy, from geometry and metaphysics to technology and mining science, situated in his time and context. That is the most important contribution to the research on Swedenborg and the history of eighteenth-century science. Additionally, in order to reach a deeper understanding of his natural philosophy and his creative mind, this book aims to penetrate his way of reasoning, with image schemas, metaphors, categories, and other cognitive abilities. In that respect this study is a contribution to the current methodological development of a cognitive history in what has been called the cognitive turn within the humanities. But the approach can also shed new light on this influential visionarys esoteric theology and doctrine of correspondences, which actually is a metaphorical system grounded in his cognitive qualities and experiences.

The verses about the vanity of writing and reading books were written by Swedenborg for his father, Bishop Jesper Swedbergs book Vngdoms regel och lderdoms spegel (Rule of Youth and Mirror of Old Age,

Books can give nourishment, but also stomach-ache. Swedenborg read and wrote indefatigably. In June 1740, at the tercentenary celebrations of Johann Gutenberg and the art of printing, Swedenborg wrote about how printing presses were propelled by the waves flowing from the source of Pallas, goddess of wisdom.) he describes how, during a voyage in space, he got into conversation with some spirits from a distant solar system. On our globe, he explained, there are remarkable sciences and arts that are unparalleled anywhere else in the universe:

such as astronomy, geometry, mechanics, physics, chemistry, medicine, optics, philosophy. I went on to mention techniques unknown elsewhere, such as ship-building, the casting of metals, writing on paper, the diffusion of writings by printing, thus allowing communication with other people in the world, and the preservation for posterity of written material for thousands of years. I told them that this had happened with the Word given by the Lord, so that there was a revelation permanently operating in our world.

With the aid of printing, people can pass on and store their thoughts and inventions for thousands of years, to future generations, to new creatures on earth. Among the immense numbers of stars and planets in the vast universe there is only one globe where the art of writing is known. Only there can sciences, mathematics, and philosophy be found.

In Swedenborgs ideas about writing, about books as grains of sand, one canas so oftenfind threads going back to earlier sources, such as classical authors or the Bible. Counting grains of sand is a classical metaphor for the impossible. Archimedes starts The Sand Reckoner from the third century BC by saying that there are some who think that the number of the sand is infinite in multitude.

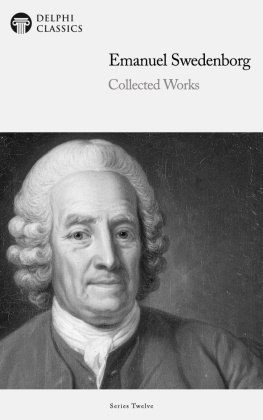

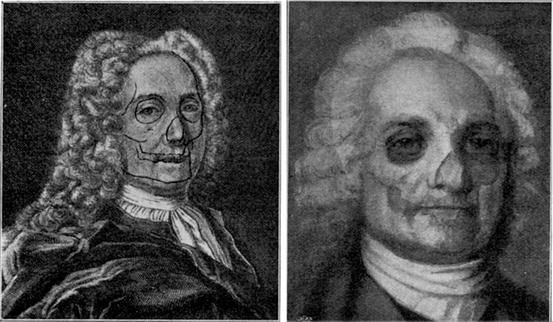

Fig. 1

Swedenborgs skull. The contours of a cranium drawn on the portrait of Swedenborg in Principia from 1734. To the right, a photographic projection of a model of the skull on a later portrait of Swedenborg. Around 1910 Johan Vilhelm Hultkrantz performed a forensic examination of a skull in Swedenborgs coffin and drew the conclusion that, despite suspicions to the contrary, it really was Swedenborgs own skull. Yet Doctor Hultkrantz was mistaken. Swedenborgs true skull was not found until it appeared at an auction at Sothebys in London in 1978, when it was purchased by the Swedish state for the reasonable price of 1,500 (Hultkrantz, The Mortal Remains of Emanuel Swedenborg (1912))

The Bible likewise contains grains of sand. Gods thoughts are more in number than the sand, the Psalter says, or as the Swedish bishop Johannes Rudbeckius renders this in his hymnal Enchiridion (1622):