IVP Books

An imprint of InterVarsity Press Downers Grove, Illinois

In memory of those who died

in New York and Washington on September 11, 2001,

around the Indian Ocean in December 2004,

in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast in August 2005,

and in Pakistan and Kashmir in October 2005

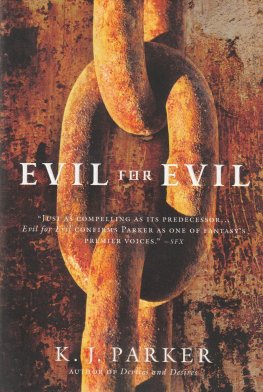

After working for some years on a major book on the resurrection, I resolved at the start of 2003 that I would turn my attention to the meaning of Jesus' crucifixion. But as soon as I began to think how I might approach the subject, I realized that there was something else I had to do first. When Christians talk about what Jesus accomplished in his death, they usually say something about his cross as the answer to, or the result of, evil. But what is evil?

The same question presented itself to me for a very different reason. Between September 11, 2001, when terrorists flew airplanes into the Twin Towers in New York and into the Pentagon in Washington, and my reflecting on the cross and the problem of evil in early 2003, the topic of "evil" had suddenly become hot. American President George W Bush had declared that there was an "axis of evil" which had to be dealt with. British Prime Minister Tony Blair announced that the task of the politician was to rid the world of evil. Commentators on the left and on the right expressed doubts about both the analysis and the solution-doubts which the war in Iraq and its aftermath have amply justified.

I turned my reflections into five lectures which I delivered at Westminster Abbey, where I was then working, in the first half of 2003. I then attempted to summarize my thesis in a television program made by Blakeway Productions and first screened on Channel 4 in the U.K. on Easter Day 2005; copies of this film are available from Blakeway (www.blakeway.co.uk). I am very grateful to David Wilson, the producer, and to Denys Blakeway himself, for understanding what I was trying to say and enabling me to communicate it in a very different medium. Those who saw the program and were puzzled by what I did not manage to say in the 49 minutes available to me may perhaps be mollified by the fuller version offered in the present book.

Having said that, I do not pretend for a moment that I have here provided a full or even a balanced treatment either of the problem of evil or, more especially, of the meaning of Jesus' crucifixion. The central chapter of this book approaches Jesus' death from one angle which I believe to be deeply fruitful, but I am well aware that a more complete account of the meaning and saving effect of Jesus' death would need to raise and answer far more questions than I have even mentioned, and to deal with biblical passages and theological and philosophical ideas for which there is no space here. I hope, however, that this will at least point in the direction of further work.

In the first lecture-now the first chapter-I used as one of my controlling images the biblical picture of the wild, untamed sea. I was then all the more horrified when, on December 26, 2004, a tsunami ripped across the Indian Ocean, smashing people and communities to pieces. Then, like the rest of the world, I had an awful sense of deja vu when Hurricane Katrina drowned New Orleans and a large section of the American Gulf Coast in August 2005. When I asked myself to whom the present book should be dedicated, I could think of no better answer than to honor the memory of those who died in those two disasters and the subsequent earthquake in Pakistan and Kashmir, along with the victims of September 11, 2001. They are a reminder that "the problem of evil" is not something we will "solve" in the present world, and that our primary task is not so much to give answers to impossible philosophical questions as to bring signs of God's new world to birth on the basis of Jesus' death and in the power of his Spirit, even in the midst of "the present evil age."

N. T. Wright

Easter 2006

The New Problem of Evil

In the new heaven and new earth, according to Revelation 21, there will be no more sea. Many people feel disappointed by this. Looking at the sea, sailing on it and swimming in it are perennial delights, at least for those who don't have to make a living by negotiating its treacherous habits and untimely bad moods. As a regular sea watcher and occasional swimmer, I share this sense of surprise and disappointment. But within a larger biblical worldview we can begin to make sense of it.

The sea is of course part of the original creation. Indeed, it appears earlier in Genesis 1 than the dry land, and both the land and then the animals come out of it. It is part of the world which God says, at the end of the six days, is "very good." But already by Genesis 6, with the story of Noah, the rising waters of the flood pose a threat to the entire world that God has made, from which Noah and his floating zoo are rescued by the warnings of God's grace. From within the good creation itself, it seems, come forces of chaos harnessed to enact God's judgment.

We then hear no more of the sea until we find Moses and the Israelites standing in front of it, chased by the Egyptians and at their wits' end. God makes a way through the sea to rescue his people and once more to judge the pagan world; it is the same story, in a way, though now in a new mode. And as later Israelite poets look back on this decisive, formative moment in the story of God's people, they celebrate it in terms of the old Canaanite creation myths: YHWH (the biblical name of the God of Israel) is King over the flood (Ps 29:10); when the floods lift up their voices, YHWH on high is mightier than they are (Ps 93:3-4); the waters saw YHWH and were afraid, and they went backwards (Ps 77:16; 114:3, 5). Thus, when the psalmist describes his despair in terms of being up to his neck in deep waters, as in Psalm 69, this is held within a context where YHWH is already known as the one who rules the raging of the sea and even makes it praise him (Ps 69:1, 34).

But then we find in the vision of Daniel 7, a passage of enormous influence on early Christianity, that the monsters who make war on the saints of the Most High come up out of the sea. The sea has become the dark, fearsome place from which evil emerges, threatening God's people like a giant tidal wave threatening those who live near the coast. For the people of ancient Israel, who were not for the most part seafarers, the sea came to represent evil and chaos, the dark power that might do to God's people what the flood had done to the whole world, unless God rescued them as he rescued Noah.

It may be (though this might take us too far off our track) that one of the reasons we love the sea is because, like watching a horror movie, we can observe its enormous power and relentless energy from a safe distance. Alternately, if we go sailing or swimming on it, we can use its energy without being engulfed by it. I suspect there are plenty of Ph.D. theses already written on what's going on psychologically when we do this, and I haven't read them. We would, of course, find our delight turning quickly to horror if, as we stood watching the waves, a tsunami were suddenly to come crashing down on us, just as our thrill at watching a gangster movie in the theater would turn to screaming panic if a couple of heavily armed thugs came out of the screen and threatened us personally. The sea and the movie, seen from a safe distance, can be a way of saying to ourselves that, yes, evil may well exist-there may be chaos out there somewhere-but at least, thank goodness, we are all right, we are not immediately threatened by it. And perhaps this is also saying that, yes, evil may well exist inside ourselves as well-there may be forces of evil and chaos deep inside us of which we are at best only subliminally aware-but they are under control: the sea wall will hold, the cops will get the gangsters in the end.