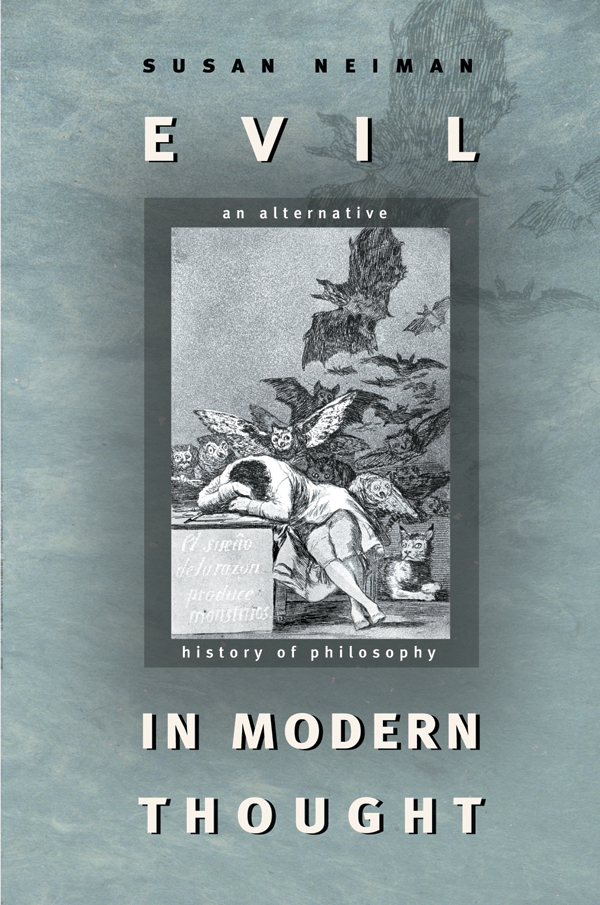

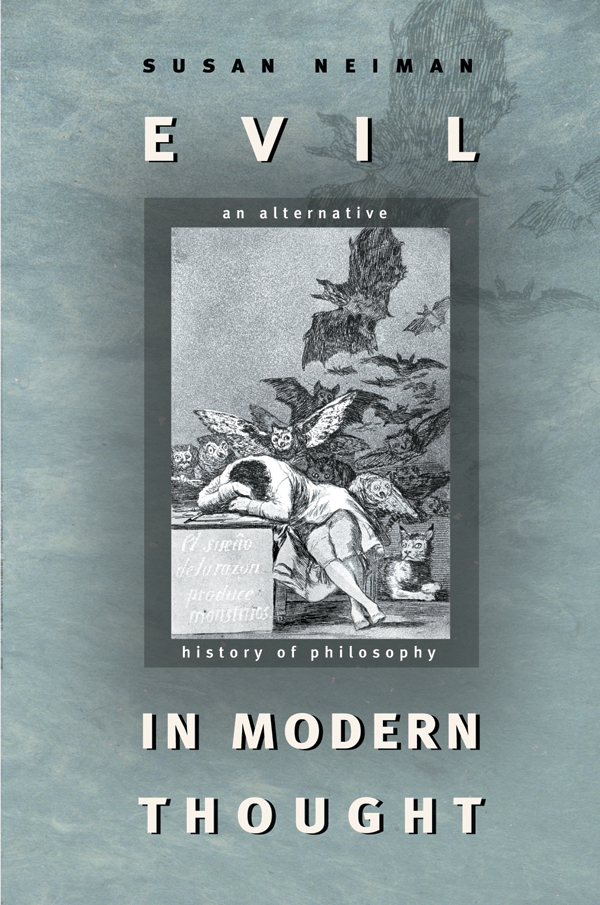

EVIL IN MODERN THOUGHT

AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY

EVIL IN MODERN THOUGHT

AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY

SUSAN NEIMAN

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

COPYRIGHT 2002 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Published by

Princeton University Press

41 William Street

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom:

Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 0-691-09608-2

British Library of Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in ITC Garamond Light

Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pupress.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR

BENJAMIN

SHIRAH

LEILA

The great assumption that what has taken place in the world has also done so in conformity with reasonwhich is what first gives the history of philosophy its true interestis nothing else than trust in Providence, only in another form.

Hegel, Introduction to the Lectures on the History of Philosophy

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Several institutions provided crucial support that gave me time to write this book. The Shalom Hartman Institute offered the most congenial place to work in the State of Israel, as well as a fellowship enabling me to devote time to research. An ACLS senior fellowship allowed me to complete much of the writing during 19992000; good fortune, and the Rockefeller Foundation, allowed me to draft the final chapter at the Villa Serboni in Bellagio.

Earlier versions of some passages appeared in the following essays: Metaphysics to Philosophy: Rousseau and the Problem of Evil, in Reclaiming the History of Ethics: Essays for John Rawls, ed. B. Herman, C. Korsgaard, and A. Reath (Cambridge University Press, 1997); Theodicy in Jerusalem, in Hannah Arendt in Jerusalem, ed. S. Ascheim (University of California Press, 2001); and What Is the Problem of Evil? in Rethinking Evil: Contemporary Perspectives, ed. M. P. Lara (University of California Press, 2001).

This book was long in the making, and provides occasion for acknowledging debts incurred before work on it began. Though none of them would entirely agree with the way Ive done it, I would like to thank the people who taught me how to do philosophy. In chronological order, I am indebted to Burton Dreben for using the resources of analytic philosophy to illuminate what he called the big picture; to Stanley Cavell for making space for culture within English-speaking philosophy; to John Rawls for showing how the history of philosophy is not merely an archive for philosophy but a part of it; to Margherita von Brentano for maintaining the Enlightenments strengths in full awareness of its weaknesses; to Jacob Taubes for making theological questions kosher for philosophical discourse. A number of friends and colleagues read the manuscript and offered vital criticism and encouragement. I am deeply if differently indebted to Richard Bernstein, Sander Gilman, Moshe Halbertal, Eva Illouz, Jeremy Bendik Keymer, Claudio Lange, Jonathan Lear, Iris Nachum, and James Ponet. Among the friends from whom I have learned, I must single out Irad Kimhi, who from the earliest stages spent countless hours helping me to think more clearly about the issues discussed here. Finally, Ian Malcolm was a superb editor, whose insight and engagement contributed much to improving the final shape of the book. Gabriele Karl provided expert and warmhearted secretarial support; Andreas Schulzs assistance was invaluable in the preparation of the bibliography.

My children had more than the usual share of burdens to shoulder during the writing of this book; they did it with more than the usual grace. A dedication is but small thanks for the patience and love with which they accompany my work.

EVIL IN MODERN THOUGHT

AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY

Introduction

The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity. (One is unable to notice somethingbecause it is always before ones eyes.) The real foundations of his inquiry do not strike a person at all.And this means: we fail to be struck by what, once seen, is most striking and most powerful.

Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, #129

The eighteenth century used the word Lisbon much as we use the word Auschwitz today. How much weight can a brute reference carry? It takes no more than the name of a place to mean: the collapse of the most basic trust in the world, the grounds that make civilization possible. Learning this, modern readers may feel wistful: lucky the age to which an earthquake can do so much damage. The 1755 earthquake that destroyed the city of Lisbon, and several thousand of its inhabitants, shook the Enlightenment all the way to East Prussia, where an unknown minor scholar named Immanuel Kant wrote three essays on the nature of earthquakes for the Knigsberg newspaper. He was not alone. The reaction to the earthquake was as broad as it was swift. Voltaire and Rousseau found another occasion to quarrel over it, academies across Europe devoted prize essay contests to it, and the six-year-old Goethe, according to several sources, was brought to doubt and consciousness for the first time. The earthquake affected the best minds in Europe, but it wasnt confined to them. Popular reactions ranged from sermons to eyewitness sketches to very bad poetry. Their number was so great as to cause sighs in the contemporary press and sardonic remarks from Frederick the Great, who thought the cancellation of carnival preparations months after the disaster to be overdone.

Auschwitz, by contrast, evoked relative reticence. Philosophers were stunned, and on the view most famously formulated by Adorno, silence is the only civilized response. In 1945 Arendt wrote that the problem of evil would be the fundamental problem of postwar intellectual life in Europe, but even there her prediction was not quite right. No major philosophical work but Arendts own appeared on the subject in English, and German and French texts were remarkably oblique. Historical reports and eyewitness testimony appeared in unprecedented volume, but conceptual reflection has been slow in coming.

It cannot be the case that philosophers failed to notice an event of this magnitude. On the contrary, one reason given for the absence of philosophical reflection is the magnitude of the task. What occurred in Nazi death camps was so absolutely evil that, like no other event in human history, it defies human capacities for understanding. But the question of the uniqueness and magnitude of Auschwitz is itself a philosophical one; thinking about it could take us to Kant and Hegel, Dostoevsky and Job. One need not settle questions about the relationship of Auschwitz to other crimes and suffering to take it as paradigmatic of the sort of evil that contemporary philosophy rarely examines. The differences in intellectual responses to the earthquake at Lisbon and the mass murder at Auschwitz are differences not only in the nature of the events but also in our intellectual constellations. What counts as a philosophical problem and what counts as a philosophical reaction, what is urgent and what is academic, what is a matter of memory and what is a matter of meaningall these are open to change.

This book traces changes that have occurred in our understanding of the self and its place in the world from the early Enlightenment to the late twentieth century. Taking intellectual reactions to Lisbon and Auschwitz as central poles of inquiry is a way of locating the beginning and end of the modern. Focusing on points of doubt and crisis allows us to examine our guiding assumptions by examining what challenges them at points where they break down: what threatens our sense of the sense of the world? That focus also underlies one of this books central claims: the problem of evil is the guiding force of modern thought. Most contemporary versions of the history of philosophy will view this claim to be less false than incomprehensible. For the problem of evil is thought to be a theological one. Classically, its formulated as the question: How could a good God create a world full of innocent suffering? Such questions have been off-limits to philosophy since Immanuel Kant argued that God, along with many other subjects of classical metaphysics, exceeded the limits of human knowledge. If one thing might seem to unite philosophers on both sides of the Atlantic, its the conviction that Kants work proscribes not just future philosophical references to God but most other sorts of foundation as well. From this perspective, comparing Lisbon to Auschwitz is merely mistaken. The mistake seems to lie in accepting the eighteenth centurys use of the word

Next page