Counter-Currents Publishing Ltd.

Counter-Currents Publishing Ltd.

Kevin I. Slaughter

Editors Introduction

Collin Clearythe enigmatic sage of Sandpoint, Idahoburst onto the intellectual scene almost ten years ago, with the publication of the first volume of the journal TYR . Along with Joshua Buckley and Michael Moynihan, Cleary was one of the founding editors of TYR , having a hand in all aspects of the first volume and contributing three substantial articles and several reviews. (Although he is now no longer involved in editing TYR , he continues to contribute to it.)

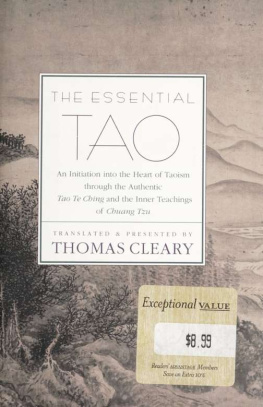

Who is Collin Cleary? He could accurately be described as a theologian of neo-paganism, specifically of the Nordic variety. He is also a Traditionalist with a capital T, meaning that he falls within the same school of thought as Ren Gunon and Julius Evola. He is a Tantrika (no mean feat for a Nordic pagan). And he is an anti-modern thinker. Cleary is a polymath who has read widely in philosophy, religion, mysticism, mythology, and literature. His principal influences are a surprising combination of figures: Martin Heidegger, D. H. Lawrence, G. W. F. Hegel, Lao Tzu, Evola (but not Gunon, interestingly), the Indologist Alain Danilou, and the Nordic pagan theorist Edred Thorsson. All of Clearys interests and influences are on display in the remarkable essays collected in this volume.

The Leitmotiv of these essays is the hypothesis that our ancestors possessed a special kind of openness which made them aware of the godssomething that we have now lost. In other words, Cleary does not believe that our ancestors invented their gods; instead, they were literally aware of aspects of reality now closed to us. Cleary believes that this openness is closely bound up with openness to the natural world (though they are not, strictly speaking, the same thing), and that the loss of this state of mind is the root of most of our modern problems: environmental abuse, the collapse of communities, the breakdown of relations between the sexes, the folly of social engineering, moral relativism, scientism, and much else. In Clearys view, therefore, the recovery of this openness would not just be simply a return to belief in the gods, but also an antidote to modern decadence and dissolution.

How exactly can openness be recovered? This is the difficult problem Cleary poses for himself. In one way or another, he deals with it in every essay in this volume. What we find in Clearys body of work is not the same ideas repeated over and over, applied in cookie-cutter fashion to a succession of issues, but an approach that develops over time. From the first essay (Knowing the Gods) to the last (on the autobiography of Alejandro Jodorowsky), we find Cleary continually elaborating and refining his answer to how we might recover the lost openness enjoyed by our ancestors.

Knowing the Gods is Clearys first major essay, published in the flagship volume of TYR . The central feature of the piece is an insistence that we must eschew all attempts to explain the gods or our ancestors experience of them. Why? Quite simply because trying to explain the godstrying to say, for example that Thor is just x (or the experience of Thor is really the experience of x)reflects the standpoint of modern rationalism and scientism. To approach the gods in such a fashion is therefore to adopt a mindset that guarantees we will be unable to recover the perspective of our ancestorswho most certainly did not reflect on what the gods really were (or what the experience of them really was).

In effect, Cleary proposes a strategy for coming to knowledge of the gods: assume that the gods are a brute fact and that we have lost our ability to know them. Then address the issue of reconstructing or restoring the state of mind that made possible our ancestors experience of the gods. He takes this position, in part, simply because of the gross psychological implausibility of the claim that our ancestors simply made up their gods and then chose to believe in them. As he makes clear in a subsequent essay, Cleary is not insisting that we should believe that Thor wields a literal hammer, or that the gods of the Greeks are literally to be found atop Olympus (a claim the ancients, who had been to the top of Olympus, all knew to be literally false). But he believes that in speaking of the gods, our ancestors were speaking of, again, some aspect of reality of which we seemingly can no longer even conceive. To recover this, Clearly makes a Heideggerian proposal: that we adopt the standpoint of openness to being.

Cleary tells us that openness to the gods begins with openness to the being of things as such. He argues that the flight of the gods begins not specifically with our disbelieving in them, but in the adoption of a more general attitudewhat Heidegger calls das Gestell (translated into English, rather imperfectly, as enframing). This is the attitude of regarding all that exists as essentially raw material that waits upon human beings to rework or perfect it. This mindset is, in fact, the essence of modernity.

In a real sense modern people do not regard the things of this world as possessing any intrinsic being or nature. They are all pure potential, waiting for us to put our stamp upon them. Trees are potential pencils, a mighty river (to use Heideggers famous example) is a potential power source, and the men of today are, with proper re-education, the new and improved men of tomorrow. For modern people, therefore, things have no real nature of their owntheir nature is always something that has yet to emerge, with our assistance. And so modernity always orients itself toward the future, toward a promise of perfection to come. For Cleary, what causes the flight of the gods is just this attitude, which recognizes no limits on human power and rejects the idea of things having any definite, intrinsic being.

Clearys essay Summoning the Gods (written for the second volume of TYR ) provides a more expansive answer as to why he thinks this is the case. In this essay, Cleary argues that the experience of the gods just is an experience of wonder in the face of the being of things. Thus, openness to the gods presupposes openness to being-as-such. The experience of a god is mans wonder in the face of some aspect of reality he has not created, which awes him with its beauty, or power, or dreadfulness. We are struck by the sheer facticity of things; we wonder that certain things should be at all, or be the way that they are. It is like the Zen experience of satori , in which one is suddenly struck with awe before the simple fact that the rose bush is , or that the storm is . For Cleary, this experience is in fact the intuition a god. The gods thus might be described (and Cleary toys with this expression) as regions of being, which have been personified and assigned iconographies and mythologies.

Clearly has not violated the strictures he laid down in Knowing the Gods: the subsequent essay does not attempt to explain away the gods at all. In other words it does not reduce the experience of the gods to something else, thereby deflating and invalidating it. Like Rudolf Otto, Cleary is attempting a phenomenological description of divine presence: how the divine shows up to us; how we become aware of it. Clearys ideas about how our ancestors encountered their gods are based partly upon the study of classical texts and upon philosophical speculation, guided by a sense of what is psychologically and culturally plausible. They are also partly inspired by Clearys own personal experience: the result of following the recommendations he lays out in the original appendix to Knowing the Gods (published here for the first time).