THE PEOPLE AND THE BOOKS

TO MY TEACHERS

THE PHRASE PEOPLE OF THE BOOK DOES NOT ORIGINATE in Judaism. It is, rather, an Islamic title, used in the Koran to designate both Jews and Christianspeoples who possess their own revelations from God in the form of holy scripture. Followers of these faiths were accorded an intermediate place in Islamic society, not fully equal to Muslims but better off than outright pagans. Jews, however, have embraced the People of the Book as a peculiarly fitting description, even a title of honoras though Jewish culture has a special affinity for books, as though reading and writing are in some sense constitutive of Jewish identity.

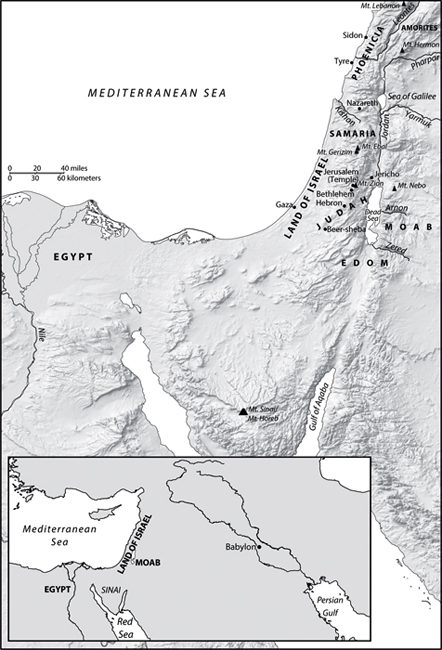

And it is true that for most of Jewish history, books were not just one element in Jewish culture; they were the core of that culture, the binding force that sustained a civilization. To study the history of most peoples is to learn about wars and empires, military heroes and political reformers, great buildings and beautiful artworks. The Jews, too, once had their share of these worldly achievements. The Bible is a record of Israels generals and kings, and of monuments like the Jerusalem Temple. But in the year 70 CE the Temple was destroyed by a Roman army, and the country of Judea was abolished. For the next nineteen centuries, until the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, the history of Judaism would not be told primarily in political terms. It would be, instead, a history of books.

The canonical books at the heart of Jewish religion are the Bible and the Talmud. These are the texts that have taught many generations of Jews their religious duties and their conception of God. They have also been the foundation of an unbroken tradition of commentary and codification, which is responsible for some of the greatest monuments of Jewish creativityfrom the Talmudic commentary of Rashi, the medieval French rabbi, to the Shulchan Aruch, the digest of laws that governs Orthodox Jewish practice to this day. In the map of Jewish writing, the law and its commentaries are the central continent. To master them, however, requires a lifelong training available to few people, usually the most devout; and so they appear only incidentally in the pages that follow.

What remains is a literature whose richness and variety testify to the great length and breadth of Jewish history. The books explored in the following pages were written over a span of more than twenty-five hundred years, in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin, Arabic, Yiddish, and German. (I have read and cited them in English; the translations I use can be found in the selected bibliographies at the end of each chapter. Ive followed these sources for the spelling of proper names, which can often vary in translation.) They include fiction and history, philosophy and memoir, mystical fables and moral aphorisms. Some of them are very famous, familiar to anyone who reads the Bible, while others are known primarily to historians and specialists. Taken together, however, they offer a panoramic portrait of Jewish thought and experience over the centuries. My goal in The People and the Books has been to open up these texts to the interested readerto show what they contain, how and why they were written, and what they can tell us about Judaism and Jewishness.

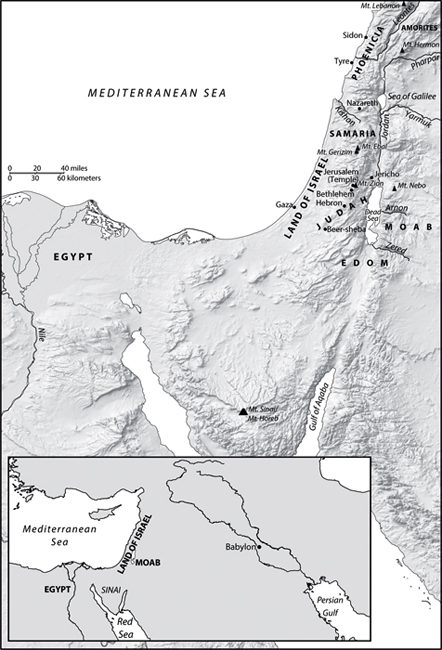

Perhaps the most striking thing that emerges from reading these books together is the remarkable continuity of Jewish thought, despite all the catastrophes and ruptures of Jewish history. From the biblical book of Deuteronomy in the seventh century BCE to the works of the Yiddish master Sholem Aleichem in the twentieth century CE, a few subjects preoccupy every kind of Jewish writer. They might be reduced to four central elements: God, the Torah, the Land of Israel, and the Jewish people. These subjects have been understood in dramatically different ways at different times, but the questions they raise keep coming back in all possible permutations. Indeed, for Judaism, God, Torah, land, and people are inseparable, so that to ask about one is to ask about the others.

Jewish writers have always wondered, for instance, about what kind of being God is. Is he the personal God who made a covenant with Abraham and Moses, or the impersonal God who created the cosmos and the laws of nature? If he is the latter, then how should we understand the Torah, with its anthropomorphic language and its often arbitrary-seeming laws? These questions have especially troubled Jews who lived at the intersection of Jewish tradition with a broader philosophical culture. That is why Philo, living in Roman Egypt in the first century CE, asked so many of the same questions as Maimonides, who lived in Muslim Egypt in the twelfth century CE. Both of them, as well as Yehuda Halevi in the twelfth century and Spinoza in the seventeenth, wondered about the Jewish rite of circumcision, which seemed so odd to many non-Jews. What was the reason for this commandment? Was it purely arbitrary, or did it encode some medical wisdom or ethical imperative or spiritual truth? And did it need some such meaning to justify its existence?

Similar questions could be asked about many Jewish laws, including those that have specific application to the Land of Israel. In the book of Genesis, God promised that land to Abraham and his descendants forever. Why, then, did God allow the Jews to lose their land and their Temple, where so many crucial rituals were enacted? And what remains of Judaism when these focal points are gone? These questions are already foreshadowed in the book of Deuteronomy in the seventh century BCE. Nearly a thousand years later, after the loss of the Second Temple, a new attempt to answer them led to the creation of rabbinic Judaism, whose ethos is so beautifully captured in Pirkei Avot, a collection of aphorisms about Jewish ethical ideals. Eight hundred years after that, the dialogue known as the Kuzari asked what the Land meant to the Jews, long after most of them had left it behind. And another eight hundred years after that, Theodor Herzl, an assimilated and secular man who knew very little about Judaism, arguedto momentous effectthat the Land of Israel was still the only salvation for the Jewish people.

For much of Jewish history, however, the Land remained an object of pious longing rather than an actual possibility. Indeed, even before the Jewish War in 6670 CE, which Josephus writes about with such ambivalent feelings, much of Jewish life was led in Diaspora, which posed its own existential challenges. The book of Esther, which was most likely written in Persia during the fourth century BCE, is perhaps the earliest Jewish book about what it means to live as a minority in a potentially hostile society. It offers perpetually relevant lessons about the importance for Jewish survival of both luck and political skill. The same dynamics reappear five hundred years later in Philos account of the Jews precarious position in Alexandria, and fifteen hundred years after that in Glckel of Hamelns offhand observations about the insecurity of the Jews of Hamburg. By the time Sholem Aleichem wrote his Tevye stories around the year 1900, the Jewish heartland of eastern Europe had come to seem like a tightening noose, as the Jews traditional strategies of survival began to fail.

Still, it is crucial not to read Jewish history merely as a series of persecutions and expulsions. Even as external threats to Jewish security appear in the following pages, so too do remarkable expressions of Jewish creativity and agency. Indeed, the transformation of worldly challenges into imaginative possibilities is one of the great achievements of Jewish mysticism. The

Next page