The I Ching

(Book of

Changes)

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY

Doing Philosophy Comparatively , Tim Connolly

The Bloomsbury Research Handbook of Chinese Philosophy and Gender , edited by Ann A. Pang-White

The Bloomsbury Research Handbook of Chinese Philosophy Methodologies , edited by Sor-hoon Tan

The Bloomsbury Research Handbook of Early Chinese Ethics and Political Philosophy , edited by Alexus McLeod

Understanding Asian Philosophy , Alexus McLeod

Most of all, for Mingmei, who has always been there for me during my seemingly endless journey to the Far Side, to translate one of the worlds most enigmatic books in the world, and also for her profound knowledge of Chinese culture, both literary and popular.

And especially for twenty-five years of love and companionship.

The I Ching

(Book of

Changes)

A Critical Translation

of the Ancient Text

Geoffrey Redmond

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

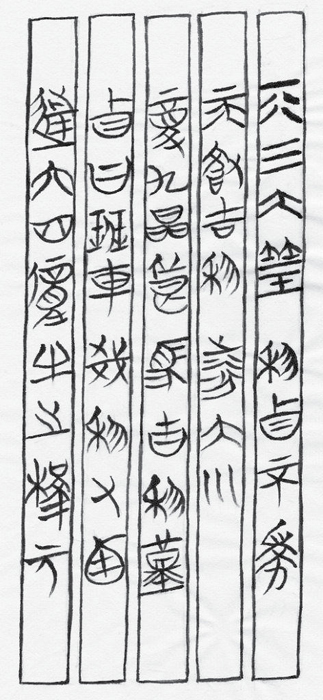

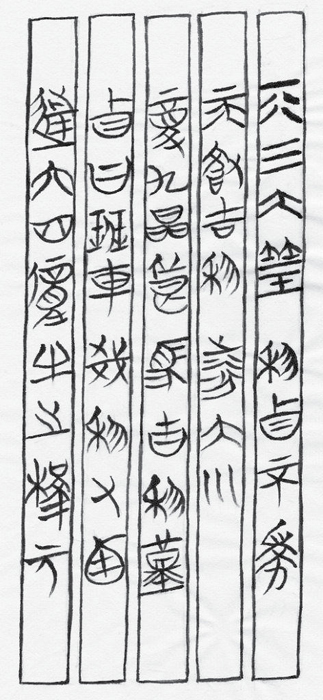

An excerpt from the oldest (c. 300 bce ) existing Zhouyi manuscript; the original is on bamboo strips. For the anecdote upon which it is based, see page 368. ( All calligraphy and illustrations by Mingmei Yip)

CONTENTS

Coming of age in the sixties, I was fascinated by what was still referred to as the mysterious Orient, as well as Western occultism, itself somewhat beholden to Asian religious and philosophical ideas. At the same time I became attracted to Chinese art, particularly Song landscape and Shang and Zhou bronzes. Western interest in China and Japan began far earlier than the sixties. It started with the early Jesuit missionaries and European philosophers, notably Gottfried Leibniz and Voltaire, who knew about China only through the accounts of others.

The sudden rise of interest in Asian religion and philosophy in the sixties was partly due to media popularization, but also because the times were hungry for new ideas, particularly for philosophies that might offer something life-changing. Through my own engagement with Chinese culture this came true for me, though not entirely in ways I expected. I had limited opportunity to pursue this interest during the long years I was engaged in the ordeal of medical training, though I did find time to acquaint myself with the Dao De Jing in the translation of Gia-fu Feng and Jane English, a work that helped me through this difficult time. While my approach to science has always been strictly empirical, I found that Asian thought offered me something that Western science did not. It is not that I thought these philosophical traditions were somehow superior to science, rather, they addressed deep human concerns that the hard sciences by their nature cannot. For this reason I have always been impatient with the notion that science and spirituality are incompatiblehumanity needs both.

I was particularly fascinated by divination, not as a means of predicting for myself but as an alternative mode of knowledge, one that many still find of value in their lives. Scientism rejects such as not empirically verifiable, but neither is the beauty of a painting verifiable, despite its enhancing life.

Neither my scientific studies nor my graduate study of renaissance and later literature spoke to me about the sort of knowledge-seeking that is the basis of divination and the esoteric more generally. It was the sixties counter-culture that prompted a fresh look at these matters, previously rejected as unworthy of serious attention. I have still not decided if the counter-cultural movement of the sixties was overall good or bad, but it did open minds to previously rejected knowledge. Much of this knowledge was deservedly rejected, but not all.

One result of my awakening to non-scientific ways of thought was fascination with the Book of Changes , variously called I Ching , Yijing , and Zhouyi . Impecunious in my student days, I deferred buying the omnipresent Wilhelm-Baynes translation, waiting for it to come out in paperback. It never did, so, once I was a resident, with the modest affluence of an actual salary, I made the financial commitment of buying the iconic hardcover volume. I found it difficult going. During my pre-medicine years as a graduate student of early English language philology I had often been frustrated by texts when I could not determine the provenance of their various components. Like those who avoid Chinese food because they want to know what they are eating, I need to know what I am reading. As presented by Wilhelm-Baynes, the text is best described as a gemisch , a Yiddish term used by biochemists to refer to a mixture of known and unknowable ingredients. Interspersed in this masterpiece of book design by the Bollingen Foundation/Princeton University Press are prolix commentaries of diverse authorship and date; and sprinkled within these are bits of the 3,000-year-old Western Zhou text, though mostly unrecognizable as translated. These commentaries intermingle more than 2,000 years of reflection on the classic, including the Ten Wings , composed centuries after the early text, and late Qing Confucians interpretations as passed on to Wilhelm by his traditionally educated Chinese informant. As if these ingredients were not enough, Jungian psychology was then slipped in by the English translator, Cary F. Baynes.

I was at last able to make progress with the Changes when in 1997 I acquired the immensely learned version of Richard Rutt, which I began to read on a sunny afternoon in Paris at the Caf de Flore, waiting for my wife to return from a meeting with a former Sorbonne classmate. I will not say I understood the Book of Changes on that afternoon but I had a sudden realization that with enough study the Changes might actually be understood. It took nearly twenty years from that moment to the translation you are now reading, but that is about average for translators of the Changes . Early on, I realized that understanding of this text is impossible without knowledge of the Chinese language of its long-ago era. I had long appreciated the aesthetic aspects of the Chinese writing system and so began a gradual study of the ancient written language, starting out by learning to write the name of my wife, Mingmei Yip , and going on from there.

How I have come to view this classic will be apparent in my translation. As I suspect is true for many translators of obscure ancient texts, the deep motivation for undertaking the translation was to be able to understand it for myselfthough also to pass on the fruit of this immense labor to anyone similarly intrigued by one of the worlds strangest classics.

My guiding principle in translating the Zhouyi , the ancient textual layer of the I Ching, is this: Since it must have made sense to those who composed it and to its early readers, it should be possible to translate it so that it makes sense to us. I believe that it should be mostly understandable to modern readers who have been given a little background about Western Zhou life. By this I mean that we should understand the meaning of most phrases, though the ways of thought will still often seem strange. In translation I have tried to avoid two extremes: making the text sound contemporary, which most existing translations do, or not adequately resolving obscurities.

There are many different ways to translate the Book of Changes ; the result depends on ones assumptions about the nature of the work and the best way to present it. Although my translation is quite different from theirs, I need to acknowledge that I could not have translated at all without extensively consulting the work of several distinguished scholars of the Zhouyi : Richard Kunst, Richard Rutt, as already mentioned, and Edward Shaughnessy. Other versions I have consulted include the works of James Legge, Wilhelm and Baynes, Gregory Whincup, and Margaret Pearson, among others.