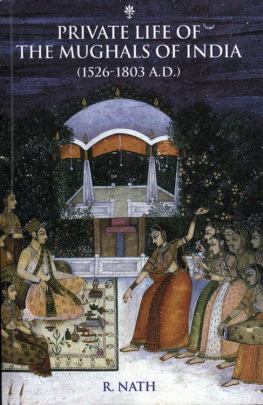

Copyright R. Nath 2005

First Published 2005

Fifth Impression 2010

Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Sales Centres:

Allahabad Bengaluru Chandigarh Chennai

Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu

Kolkata Mumbai

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Cover & Book Design by

Kapil Gupta

Printed in India by

Nutech Photolithographers

B-240, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I,

New Delhi 110 020, India

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Titled as it is, the book deals with the little known, but much scandalised, private life of the Mughals who ruled from 1526, practically to 1803 when the British captured Delhi and Agra, their nerve-centres, from them. This included the period of the reign of three great Mughals, viz. Akbar (1556-1605), Jehangir (1605-27) and Shah Jehan (1628-58), of little more than a century. They possessed not only fabulous wealth, but also the vision to found a culture-state, in the real sense of the term. Planting it in the soil as naturally as a banyan tree, they institutionalised their life, as much as their government. The former, almost completely shrouded in mystery, offers one of the most interesting aspects of medieval Indian history and culture.

Unfortunately, the official record of their day to day living which was scrupulously maintained has been lost to us.

It has been generally believed that the contemporary Persian chroniclers, living under the court patronage as they did, have blacked out this aspect of their history. Consequently, the modern historians who have ventured to write on this subject, i.e. Mughal harem life, have almost entirely depended and drew on accounts of foreign travellers. These European travellers visited the Mughal empire contemporarily and some of them were received by the Great Mughals. But they had limitations of language, culture and accessibility to correct information. They viewed the things from the point of view of European civilisation and were easily tempted to misinterpret, exaggerate and scandalise. Their narratives on Mughal life have, thus, come up to be a strange mixture of a tiny fact with a mountain of fiction. Our historians who, unfortunately relied on their travelogues, have also erred in a large measure and have tremendously contributed to the misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the Mughal lifestyle. It has been unduly romanticised.

Truly, the Persian chroniclers were either prevented from knowing what happened within the four walls of the Mughal harem owing to strict protocol and purdah, or even when they had access to this knowledge, they did not have the courage to write on this sensitive subject. The Mughal life, consequently, remained a closely guarded secret.

However, the human nature being what it is, these contemporary intellectuals' sense of wonder led them to leave clever references to their private life in a word or two, casually, in historical narratives, and one has just to read between the lines. A lifetime's rapport with these sources is needed to unravel these mysteries and, towards the end of it, one is simply amazed to see that there is probably nothing which was not known and which has not been recorded.

Thus, for example, when the historian Badaoni stated, on the eve of Akbar's marriage with the princess of Jaisalmer, that she 'obtained eternal glory by entering the female apartments', he artfully recorded that the Mughals did not practice divorce, or separation even by death, and they married for 'eternity', which is how the institution of Sohagpura (The House of Eternal Matrimony) came into being. One has just to live up with them to be able to write an authentic history on this abstract subject.

Thus does it cover such aspects of their living as food and drinks; clothes and ornaments; perfumes and incenses; addictions and intoxicants; amusements and pastimes; floor-coverings, furniture and lighting; and, of course, their sex life to which a few chapters have been devoted. How the Mughal king managed to keep a lew hundred young and beautiful women attached to his bed is as enlightening a study as it is interesting.

Though based on research, it is written without its jargon, in a simple, readable form, for the general reader.

R. NATH

Jaipur

The seclusion of women was enjoined in the Quran (XXXIII. 55) and it was the rule for respectable Muslim women to remain secluded at home, and not to travel abroad unveiled, nor to associate with men other than their husbands or such male relatives as are forbidden in marriage by reason of consanguinity. In consequence of these injunctions, which had all the force of a divine enactment, the females of a Muslim family resided in apartments which were in an enclosed courtyard and excluded from public view. This enclosure was called the harem.

The term harem was derived from the Arabic harem (literally, something sacred or forbidden); or Persian harem (sanctuary). Sanskrit harmya also means palace. It denoted seraglio, or the secluded part of the palace or residence reserved for the ladies of the Muslim household. It was also called zenanah; harem-sara; harem-gah; mahal-sara; and raniwas. Later, it was called zenani-dyodhi in the Rajput states. The chief officer of the harem was accordingly called Nazir; Nazir-i-Mahal; Nazir-i-Mashkuyah (Incharge of women's quarters) and, most popularly, Khwajah-sara (discussed in a following chapter).

The Mughal harem consisted of a large number of women of different regions, coming from different cultural milieus, speaking different languages. They were kept in strict seclusion and purdah within the four walls of the complex and their relationship with the outside world was completely severed and the proverb that a woman entered the harem by doli (bridal palanquin) and left it by arthi or janaza (funeral bier) was literally true. No male, except the king, was allowed to go into the harem and entry was barred even to his grownup sons. It was a very sensitive matter and its organisation was, therefore, extremely difficult and complicated. It goes to the credit of the Mughals that they could manage their harem efficiently and in an orderly way. It was Akbar (the Great Mughal who ruled from 1556 to 1605 A.D.), indeed, who founded the customs, traditions and institutions which guided and regulated the course of the Mughal life and culture. These were faithfully and scrupulously followed by his descendants; Jehangir (1605-27); Shah Jehan (1628-58); Aurangzeb (1658-1707) and the later Mughals (1707-1803). Abu'l Fazl, author of