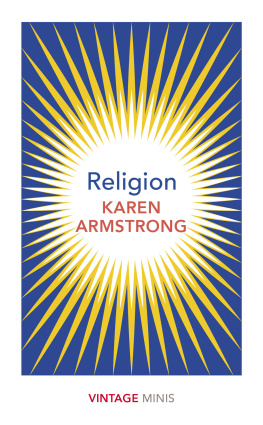

There could not be a better guide [to the Bible] than Karen Armstrong Her scholarship is immense. She has researched and written with wisdom and insight on all the major faiths and on the notion of God itself to huge acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic. Her style is never to knock down, caricature or expose, but to immerse herself in her subject and to understand what makes religions, and the religiously inclined, tick. Her short biography provides a learned but accessible history of the Bibles origins and genesis. Armstrong goes behind the authorised versions preached by the churches to recreate the order and the political and social circumstances in which the books of the Old and New testaments were first written down, amended, and then endlessly reinterpreted and recast Armstrongs great achievement, however, is that, as well as leaving you with a clearer, more historically accurate picture as to what precisely the Bible is (and isnt), she also makes you want to go back and read it again with fresh eyes. Peter Stanford, Independent

Other titles in the Books That Shook the World series:

Available now:

Platos Republic by Simon Blackburn

Darwins Origin of Species by Janet Browne

Thomas Paines Rights of Man by Christopher Hitchens

The Quran by Bruce Lawrence

Homers The Iliad and the Odyssey by Alberto Manguel

On The Wealth of Nations by P. J. ORourke

Carl von Clausewitzs On War by Hew Strachan

Marxs Das Kapital by Francis Wheen

Forthcoming:

Machiavellis The Prince by Philip Bobbitt

Copyright Karen Armstrong 2007

The moral right of Karen Armstrong to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the

copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders. The publishers will be

pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their

attention at the earliest opportunity.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3 JZ

www.groveatlantic.co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-848-87254-7

First eBook Edition: August 2010

In Memory of Eileen Hastings Armstrong (19212006)

Contents

Human beings are meaning-seeking creatures. Unless we find some pattern or significance in our lives, we fall very easily into despair. Language plays an important part in our quest. It is not only a vital means of communication, but it helps us to articulate and clarify the incoherent turbulence of our inner world. We use words when we want to make something happen outside ourselves: we give an order or make a request and, one way or the other, everything around us changes, however infinitesimally. But when we speak we also get something back: simply putting an idea into words can give it a lustre and appeal that it did not have before. Language is mysterious. When a word is spoken, the ethereal is made flesh; speech requires incarnation respiration, muscle control, tongue and teeth. Language is a complex code, ruled by deep laws that combine to form a coherent system that is imperceptible to the speaker, unless he or she is a trained linguist. But language has an inherent inadequacy. There is always something left unsaid; something that remains inexpressible. Our speech makes us conscious of the transcendence that characterizes human experience.

All this has affected the way we read the Bible, which for both Jews and Christians is the Word of God. Scripture has been an important element in the religious enterprise. In nearly all the major faiths, people have regarded certain texts as sacred and ontologically different from other documents. They have invested these writings with the weight of their highest aspirations, most extravagant hopes and deepest fears, and mysteriously the texts have given them something in return. Readers have encountered what seems like a presence in these writings, which thus introduce them to a transcendent dimension. They have based their lives on scripture practically, spiritually and morally. When their sacred texts tell stories, people have generally believed them to be true, but until recently literal or historical accuracy has never been the point. The truth of scripture cannot be assessed unless it is ritually or ethically put into practice. The Buddhist scriptures, for example, give readers some information about the life of the Buddha, but have included only those incidents that show Buddhists what they must do to achieve their own enlightenment.

Today scripture has a bad name. Terrorists use the Quran to justify atrocities, and some argue that the violence of their scripture makes Muslims chronically aggressive. Christians campaign against the teaching of evolutionary theory because it contradicts the biblical creation story. Jews argue that because God promised Canaan (modern Israel) to the descendants of Abraham, oppressive policies against the Palestinians are legitimate. There has been a scriptural revival that has intruded into public life. Secularist opponents of religion claim that scripture breeds violence, sectarianism and intolerance; that it prevents people from thinking for themselves, and encourages delusion. If religion preaches compassion, why is there so much hatred in sacred texts? Is it possible to be a believer today when science has undermined so many biblical teachings?

Because scripture has become such an explosive issue, it is important to be clear what it is and what it is not. This biography of the Bible provides some insight into this religious phenomenon. It is, for example, crucial to note that an exclusively literal interpretation of the Bible is a recent development. Until the nineteenth century, very few people imagined that the first chapter of Genesis was a factual account of the origins of life. For centuries, Jews and Christians relished highly allegorical and inventive exegesis, insisting that a wholly literal reading of the Bible was neither possible nor desirable. They have rewritten biblical history, replaced Bible stories with new myths, and interpreted the first chapter of Genesis in surprisingly different ways.

The Jewish scriptures and the New Testament both began as oral proclamations and even after they were committed to writing, there often remained a bias towards the spoken word that is also present in other traditions. From the very beginning, people feared that a written scripture encouraged inflexibility and unrealistic, strident certainty. Religious knowledge cannot be imparted like other information, simply by scanning the sacred page. Documents became scripture not, initially, because they were thought to be divinely inspired but because people started to treat them differently. This was certainly true of the early texts of the Bible, which became holy only when approached in a ritual context that set them apart from ordinary life and secular modes of thought.

Jews and Christians treat their scriptures with ceremonial reverence. The Torah scroll is the most sacred object in the synagogue; encased in a precious covering, housed in an ark, it is revealed at the climax of the liturgy when the scroll is conveyed formally around the congregation, who touch it with the tassels of their prayer shawls. Some Jews even dance with the scroll, embracing it like a beloved object. Catholics also carry the Bible in procession, douse it with incense, and stand up when it is recited, making the sign of the cross on forehead, lips and heart. In Protestant communities, the Bible reading is the high point of the service. But even more important were the spiritual disciplines that involved diet, posture and exercises in concentration, which, from a very early date, helped Jews and Christians to peruse the Bible in a different frame of mind. They were thus able to read between the lines and find something new, because the Bible always meant more than it said.

Next page