Introduction

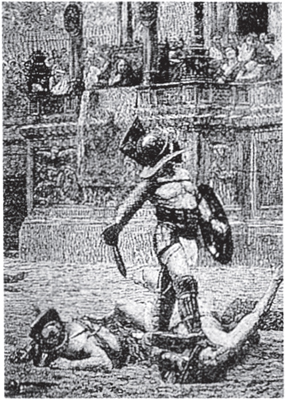

THE GLADIATOR

The ancient Romans loved gladiators. They loved the men, the weapons, the fighting and the bloodshed. They also loved the death. Bathed in the fierce heat of the Mediterranean sun, the Romans rejoiced in the blood of the dead and the dying, for in so doing they showed the qualities that had made their civilisation great and powerful. They demonstrated their utter contempt for suffering and death.

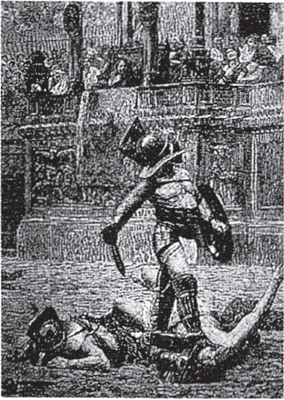

The great amphitheatres of Rome and her provinces were routinely packed with spectators, who watched men fight bloody battles, both with each other and with a dazzling array of wild and dangerous animals. Awful violence stalked the arenas in the form of sword, arrow, trident, tooth and claw, of an intensity that we can barely now imagine. In fact, as we shall see, the man-to-man combats themselves, in which countless thousands of men died, were by no means the most bloodthirsty events on show. In later years they were preceded by the wild animal hunts where men fought with ferocious beasts, often winning, but sometimes being torn to pieces. The arena was also a place of public executions, where men and women were thrown defenceless to the beasts. Their excruciating suffering brought forth cheers and applause from the spectators; to be horrified or even mildly upset by such sights was considered a pitiful and un-Roman weakness.

The gladiators themselves were the superstars of their day, lusted after by both women and men. Their celebrity status ensured that they were followed by crowds of adoring fans whenever they went out into the streets. At the same time, the nature of their profession all but ensured a horribly violent end. While some gladiators became wealthy on the prizes given to them after a victory and were able to enjoy a comfortable retirement, most did not live long enough and met their deaths in a vast expanse of hot, gore-stained sand, the roar of the blood in their ears drowned out by the screams of the crowd.

And yet in a curious paradox that lies at the heart of the secret history of gladiators, what the crowd loved they also held in the greatest contempt. The Roman people looked down on their gladiators even as they cheered their triumphs and howled abuse at their defeats.

Their enjoyment of the spectacle, however, is not disputed. The vast majority of people today would doubtless turn away in utter horror from the events of the arena. To watch a man or woman being ripped apart or eaten alive by a wild beast would be too much to bear even once, let alone for a whole day, or even many days. Nevertheless, what the historian Michael Grant has called the nastiest blood-sport ever invented was much loved in ancient Rome, and it remains one of the most troubling aspects of a culture that bequeathed to the world so much that is noble and beautiful.

But at the same time, it is a serious mistake to consider these spectacles purely in the context of modern morality. To apply our own values to a civilisation two thousand years removed in history is absurd, and will certainly not help us to understand the games or the reasons for their development. In our own age, human life is prized and respected above all else (at least in theory); to inflict suffering on others for the sake of enjoyment is considered perverse and incomprehensible. But such a perspective simply did not exist in the ancient world. The morality of the Roman state was more complex. They avoided pointless cruelty whenever possible, and nowhere more strikingly than in their treatment of vanquished nations. Revenge was not something to which the Romans surrendered easily. Instead, they calculated that treating their defeated enemies well would avoid stoking up the sort of trouble that would interfere with the profitable running of the new province. They massacred people to be sure, and brought many prisoners of war to meet their deaths in the arena, but this tended to be a last resort, a means of dealing finally with an irreconcilable foe.

The punishments meted out before the spectators, which included the most awful tortures, were dreadful and cruel to a truly extraordinary degree but they were not arbitrary. They were performed for specific reasons, based on the nature of the crime committed and on the level of suffering caused to the victim of the crime.

Although we should view the events of the arena free of modern preconceptions, it is interesting nonetheless to trace the legacy of the games in our own time. Most of us follow pursuits that have clear antecedents in the gladiatorial shows of antiquity. In an echo of the wild beast hunts of the arena, people in Britain still don special clothes and ostentatiously hunt the fox. Our own sportsmen, too, are merely the pale echoes of the ancient fighters; our fencers use blunt rapiers instead of swords and tridents, and serious injuries are rare. Our footballers, rugby players and tennis players display their skill and aggression before thousands of screaming spectators, with millions more watching on television. When a football match is over, it is not entirely unknown for the teams supporters to take to the streets and engage in battles with each other. Injuries and deaths occur, and those who consider themselves civilised bemoan the violence and bloodshed. This is exactly what happened in the ancient world: on the days when games were held, fans from rival towns would hurl abuse at each other, write insulting graffiti on walls, a flashpoint would be reached and the violence would commence.

As for the Roman love of violence, we cannot, in all honesty, make any serious claim that our own culture really abhors violence. As more than one commentator on the ancient world has noted, modern society still feels the need to watch violent events, whether they be at a boxing match or spattered across the cinema screen. The wars we wage (whether for good reasons or bad) have become another branch of the entertainment industry, thanks to the ubiquity of electronic media, which includes cameras attached to the nose-cones of rockets. We should therefore ask ourselves how easy it is to condemn ancient societies such as Rome for their cruelty, when our own politicians blandly justify the bombing and incineration of innocent civilians in other countries, or profit from the sale of weapons to repressive regimes abroad.