THE GOLDEN THREAD

The Golden Thread

The Story of Writing

Ewan Clayton

Copyright Ewan Clayton, 2013

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication is available

ISBN 978-1-61902-350-5

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, Ian and Clare Clayton

Contents

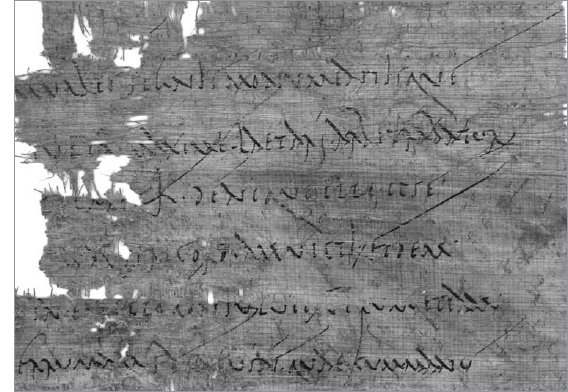

We are at one of those turning points, for the written word, that come only rarely in human history. We are witnessing the introduction of new writing tools and media. It has only happened twice before as far as the Roman alphabet is concerned once in a process that was several centuries long when papyrus scrolls gave way to vellum books in late antiquity, and again when Gutenberg invented printing using movable type and change swept over Europe in the course of just one generation, during the late fifteenth century. Changing times now mean that for a brief period many of the conventions that surround the written word appear fluid; we are free to re-imagine the quality of the relationship we will make with writing, and shape new technologies. How will our choices be informed how much do we know about the mediums past? What work does writing do for us? What writing tools do we need? Perhaps the first step towards answering these questions is to learn something of how writing got to be the way it is.

My own involvement with these questions began when I was twelve years old and I was put back into the most junior class of the school to relearn how to write. I had been taught three different styles of handwriting in my first four years of schooling and as a result I was hopelessly confused about what shapes letters ought to be. I can still remember bursting into tears aged six when I was told my print script f was wrong in this class f had lots of loops, and I simply could not understand why.

Being back in the bottom class was ignominious. But my family and family friends gave me books on writing well. My mother gave me a calligraphy pen set. My grandmother lent me a biography to read: a life of Edward Johnston, a man who lived in the village where I had my early schooling. He was the person who had revived an interest in the lost art of calligraphy in the English-speaking world at the beginning of the twentieth century. It turned out that my grandmother knew him, she used to go Scottish country dancing with Mrs Johnston, and my godmother, Joy Sinden, had been one of Mr Johnstons nurses. Tell me, he had said to her in the dark watches of one night, in his slow, deliberate, sonorous voice, What would happen if you planted a rose in a desert? I say try it and see.

Johnston developed the typeface that London Transport uses to this day. I was soon hooked on pens and ink and letter-shapes and so began a lifelong quest to discover more about writing.

Several other experiences enriched this quest. My grandparents lived in a community of craftspeople near Ditchling in Sussex, founded in the 1920s by the sculptor and letter-cutter Eric Gill. Next door to my grandfathers weaving shed was the workshop of Joseph Cribb, who had been Erics first apprentice. On days off from school I was allowed to go into Josephs workshop, where he showed me how to use a chisel and carve zigzag patterns into blocks of white limestone. He also showed me how to cut the V-shaped incisions that carved letters are made from. I acquired a sense of where letters had begun. Then, after leaving university, I trained as a calligrapher and bookbinder and went on to earn my living in the craft. It meant I learned to cut a quill pen, to prepare parchment and vellum for writing and to make books out of a stack of smooth paper, boards and glue, needle and thread.

In my twenties, after a serious illness, I decided to enter a monastery. I lived there for four years, first as a layman and then as a monk. I thought it would mean turning my back on calligraphy for ever, but I was wrong. The Abbot, Victor Farwell, had a favourite sister, Ursula, who had once been the secretary of the Society of Scribes and Illuminators, to which I belonged. She saw my name on the list of monks and said to her brother, You must let him practise his craft. So like a scribe in days of old, I became a twentieth-century monastic calligrapher. But I learned something else there also. When many hours of the day are spent in silence, words come to have a new power. I learned to listen and read in new ways.

Finally, when I left the monastery in the late 1980s, there was one more unusual experience awaiting me. I was hired as a consultant to Xerox PARC, the Palo Alto Research Center of the Xerox Corporation in California. This was the lab that invented the networked personal computer, the concept of Windows, the Ethernet and laser printer and much of the basic technology that lies behind our current information revolution. It is where Steve Jobs first saw the graphical user interface which gave the look and feel to the products from Apple that we have all come to know so well. So when Xerox PARC wanted an expert on the craft of writing to sit alongside their scientists as they built the brave new digital world we now all live in somehow I became that person. It was a life-changing experience and transformed my view of what writing is.

Crucial to this experience was David Levy, a computer scientist whom I had met while he was taking time out to study calligraphy in London. It was he who invited me out to PARC and from whom I learned the essential perspectives that have shaped this history. So I think it is to PARC and to David Levy in particular that I owe a debt of gratitude for bringing me to write this story.

So far my experience of what it means to be literate has been one of contrasts, from monastery to high-tech research centre, quill pen and bound books to email and the digital future. But throughout my journey I have found it important to hold past, present and future in a creative tension, neither to be too nostalgic about the way things were nor too hyped-up about the digital as the answer to everything salvation by technology. I see everything that is happening now the web, mobile computing, email, new digital media as in continuity with the past. There are two things of which we can be certain: first, not every previous writing technology will disappear in years to come, and second, new technologies will continue to come along every generation has to rethink what it means to be literate in their own times.

Next page