Copyright 1997, 2011 by Atlantide Editoriale S.r.l.

English-language translation copyright 2000, 2011 by Arcade Publishing, Inc.

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Originally published in Italian under the title In cosa crede chi non crede? English-language edition arranged through the mediation of Eulama Literary Agency.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-599-1

Contents

Introduction

by Harvey Cox

When the Italian newspaper La Correra de la Serra invited novelist-scholar Umberto Eco and bishop-scholar Carlo Maria Martini to engage in an exchange of views on its pages, the editors had obviously hit on a fresh and imaginative idea. But I doubt they could possibly have foreseen how brilliant the result of their conception would turn out to be. The Eco-Martini correspondence lifts the possibility of intelligent conversation on religion to a new level. It proves that the partners in such a discussion can probe and challenge and still remain respectful, even congenial. These letters are now being translated into a number of languages and will appear all over the world. It is all for the good. For American readers, it might be helpful to know a bit more about the participants in the argument.

In Ecos labyrinthine novel Foucaults Pendulum, one character says to another, I was born in Milan, but my family came from Val dAosta.

Nonsense, the other replies, You can always tell a genuine Piedmontese immediately by his skepticism.

Im a skeptic, says the first.

No, replies his interlocutor, youre only incredulous, a doubter, and thats different.

The reader has to wait a few more pages for Eco to pick up this twisted thread. But he does. And what he says might have served as a foreword to this remarkable correspondence.

Not that the incredulous person doesnt believe in anything. Its just that he doesnt believe in everything. Or he believes in one thing at a time. He believes in one thing only if it somehow follows from the first thing. He is nearsighted and methodical, avoiding wide horizons. If two things dont fit, but you believe both of them, thinking that somehow, hidden, there must be a third thing that connects them, thats credulity.

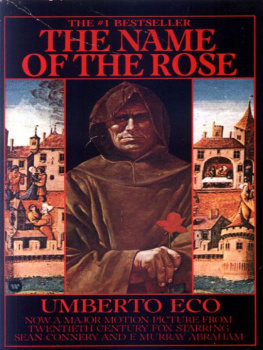

Umberto Eco was born in 1932 in Alessandria, in the Piedmont area of Italy. Before becoming a renowned scholar in the field of semiotics (the branch of philosophy dealing with signs and symbols), he studied the aesthetic theories of the Middle Ages. At the University of Turin he wrote his thesis on the aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas. He is now professor of semiotics at the University of Bologna. By his own account Eco was a practicing Catholic until the age of twenty-two. But he is not an angry, antireligious ex-Catholic. He even seems at times to speak about his lost faith with a hint of regret, and suggests that the solid sense of morality that underlies his life and his writing may well have derived from his earlier Catholic formation. That formation is highly evident, some might even say on display, in his writing. His novel Foucaults Pendulum makes extensive references to the medieval Templars and the Corpus Hermeticum. And who can forget the Latin citations, like the illuminated letters that embellish old hand-copied biblical texts, that garland each chapter heading in The Name of the Rose? If they were used by other writers, the average reader might have found these quotations a bit ostentatious. But, for some reason, we let Eco get away with them. Maybe because the luster of the whole novel and his evident command of European religious history demonstrate that he is not faking. He can write with equal ease about philosophy and aesthetics, Thomas Aquinas and James Joyce, computers and the Albigenses. And this is what makes him such a fascinating and, I would say, from an American perspective enviable collaborator in this conversation. Would that we American religionists had minds like his to engage with in this country, thinkers who know what they are talking about when they disagree with theologians, interlocutors who are incredulous but not principled skeptics. Would that we had dialogue partners who, as Eco himself puts it, may not themselves believe in God, but realize how arrogant it would be to declare, for this reason, that God does not exist. Eco is one of those mature sages who is not interested in refuting religious believers but in illuminating genuine differences and finding common ground.

In his first letter to Martini, Eco suggests that they both aim high. They do. There are no rhetorical gambits, no cheap shots. When they struggle with famously controversial questions, like abortion and womens ordination, they do not trample the familiar ground but delve into the underlying paradigms and historical processes that inform today's arguments. In his own terms, Eco is a man marked by a restless incredulity, not a closed skepticism.

Carlo Maria Martini is no more interested in refuting nonbelievers than Eco is in tripping up Christians. He is also a relentless searcher for common ground. I once heard him tell a large crowd of listeners that when he speaks about believers and nonbelievers, he does not have two different groups of people in mind. He says he means, rather, that in all of us there is something of the believer and something of the nonbeliever, and this, he added, is true of this bishop as well. It is unusual to find a prominent agnostic intellectual, like Eco, who is so open to the deepest questions of faith. It is also unusual to find a prince of the Church who is so open to the serious questions of a thoughtful agnostic.

Martini was born in Turin in 1927 and like his correspondent studied philosophy and theology. But then he traveled in a different direction. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1952 and became a member of the Society of Jesus. Beginning in 1978 he served as the Rettore Magnifico (rector) of the Gregorian University in Rome, the most prestigious Roman Catholic university in the world. For the past twenty years he has been the Archbishop of Milan. In December 1979 Pope John Paul II named him a cardinal. A broadly, humanely educated man, Martini is a respected scholar of the New Testament. His name appears as one of the editors of the most widely used critical edition of the Greek New Testament. In addition to his scholarly works he is a highly prolific writer of spiritual books for laypeople. He is also one of the leading ecumenical churchmen of Europe and takes special interest in the relations of Christians to Jews. Although he himself dismisses the possibility out of hand, Martini has been spoken of as a possible future pontiff.

Next page