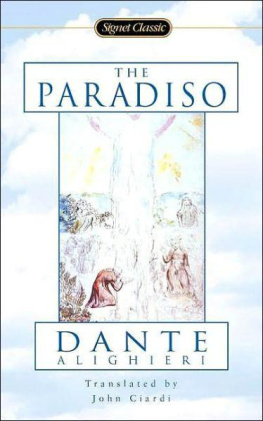

THE DIVINE COMEDY: PARADISO

A Bantam Book PUBLISHING HISTORY

The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, translated by Allen Mandelbaum, is published in hardcover by the University of California Press:

Volume I, Inferno (1980);

Volume II, Purgatorio (1981);

Volume III, Paradiso (1982). Of the three separate volumes of commentary under the general editorship of Allen Mandelbaum, Anthony Oldcorn, and Charles Ross,

Volume I: The California Lectura Dantis: Inferno was published by the University of California Press in 1998. For information, please address University of California Press, 2223 Fulton St., Berkeley, CA 94720. Bantam Classic edition published February 1986 Bantam Classic reissue edition / August 2004 Published by Bantam Dell A Division of Random House, Inc. New York, New York All rights reserved English translation copyright 1984 by Allen Mandelbaum Drawings copyright 1984 by Barry Moser Drawing, The Universe of Dante, copyright 1982 by Bantam Books Student notes copyright 1986 by Anthony Oldcorn and Daniel Feldman Cover art copyright 2004 by Jacopo Marieschi Cover photo copyright by Cameraphoto Arte, Venice / Art Resource, NY No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

Bantam Books and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

ISBN9780553212044 eBook ISBN9780553900545 v4.1 a

This translation of the PARADISO

is inscribed toToni Burbank and Stanley Holwitz,

whose DOPPIO LUME S ADDUA

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Paradiso is a poem of spectacle, of wheeling shapes that enter and exit, form, re-form, and dis-form; of voices that discourse out of their faceless flames; of letters and words spelled out across the heavens by living lights in flight; of flames that shape the remarkable Eagle; of the vast amphitheater of the Celestial Rose in the tenth and final heaven, the Empyrean, where the blessed range in carefully orchestrated ranks.

ISBN9780553212044 eBook ISBN9780553900545 v4.1 a

This translation of the PARADISO

is inscribed toToni Burbank and Stanley Holwitz,

whose DOPPIO LUME S ADDUA

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Paradiso is a poem of spectacle, of wheeling shapes that enter and exit, form, re-form, and dis-form; of voices that discourse out of their faceless flames; of letters and words spelled out across the heavens by living lights in flight; of flames that shape the remarkable Eagle; of the vast amphitheater of the Celestial Rose in the tenth and final heaven, the Empyrean, where the blessed range in carefully orchestrated ranks.

That expanse is such that when, some two-thirds of the way through Paradise, the voyager turns his gaze back and downward toward the earth, he sees ): this globe in such a way that Ismiled at its scrawny imageAnd all the seven heavens showed to metheir magnitudes, their speeds, the distancesof each from each. The little threshing floorthat so incites our savagery was allfrom hills to river mouthsrevealed to me Such cosmic expanse and order does admit of likeness to spacious waters : Therefore, these natures move to different portsacross the mighty sea of being, eachgiven the impulse that will bear it on. This impulse carries fire to the moon;this is the motive force in mortal creatures;this binds the earth together, makes it one. But that expanse does not allow us solitude or intimacywith one exception: our intimate entry into the making of the poem, into the atelier, forge, foundry, workshop, mind and heart, of the maker-orchestrator. Here we find the exilic despair that was so imperative a source of the energies and exhilaration of a work unlike anything Dante had completed before. That despair forms the bitter part of the burden of the prophecy): You shall leave everything you love most dearly:this is the arrow that the bow of exileshoots first.

You are to know the bitter tasteof others bread, how salt it is, and knowhow hard a path it is for one who goesdescending and ascending others stairs. And here we find the pride that this terminal cantica engenders, Dantes sense of the uniqueness of this work as against any wrought prior to him (): The waves I take were never sailed before;Minerva breathes, Apollo pilots me, and the nine Muses show to me the Bears. And what I now must tell has never beenreported by a voice, inscribed by ink, never conceived by the imagination There is prideand there is the nakedly buoyant, joyous presumption, and even fleeting complacency, of one who contemplates not only from the heights): O senseless cares of mortals, how deceivingare syllogistic reasonings that bringyour wings to flight so low, to earthly things!One studied law and one the Aphorismsof the physicians; one was set on priesthoodand one, through force or fraud, on rulership;one meant to plunder, one to politick;one labored, tangled in delights of flesh, and one was fully bent on indolence;while I, delivered from our servitudeto all these things, was in the height of heavenwith Beatrice, so gloriously welcomed. And in Dantes envisioning of this ever-widening expanseso unlike the ever-narrowing hellish voyage to the deepest pit, and the hopeful, ever-narrowing voyage to the Mount of Purgatorys summitwe are asked to share the travail of the writer, the constraints and limits of speech and memory, as he struggles with magnitudes.): Now, reader, do not leave your bench, but stayto think on that of which you have foretaste;you will have much delight before you tire. I have prepared your fare; now feed yourself, because that matter of which I am madethe scribe calls all my care unto itself. also asks us to enterintimatelyinto his cares and concerns at his own bench. But each of the chimings on obstacles and barriers, on the immensity of the task, on its impossibility, only serves to magnify the dimensions and intensity of the visionwhether it be the vision of the smile of Beatrice, or of the happiness of St.

Peter coming to greet Beatrice, or of the mystery of the Incarnation. The full force of these visions rests in and rises from the temporal shapes and duration of fabulation in the Comedy, a long poem, long in the time of its making (this work so shared by heaven and by earth/ that it has made me lean through these long years, ): I was within the heaven that receivesmore of His light; and I saw things that hewho from that height descends, forgets or cannot speak; for nearing its desired end, our intellect sinks into an abyssso deep that memory fails to follow it. If all the tongues that Polyhymniatogether with her sisters made most richwith sweetest milk, should come now to assistmy singing of the holy smile that litthe holy face of Beatrice, the truthwould not be reachednot its one-thousandth part