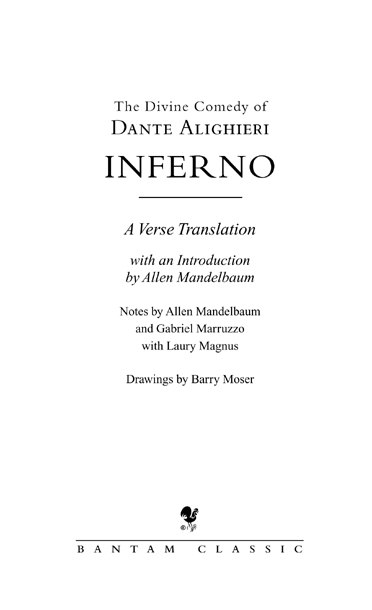

Dante Alighieri - Inferno

Here you can read online Dante Alighieri - Inferno full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1982, publisher: Bantam Classics, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

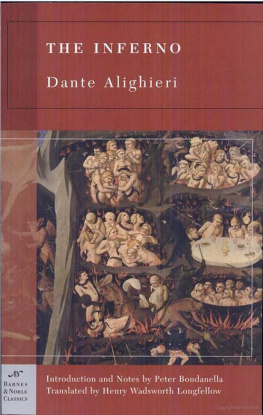

- Book:Inferno

- Author:

- Publisher:Bantam Classics

- Genre:

- Year:1982

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Inferno: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Inferno" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Inferno — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Inferno" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

DANTE ALIGHIERI was born in Florence, Italy, in 1265. His early poetry falls into the tradition of love poetry that passed from the Provenal to such Italian poets as Guido Cavalcanti, Dantes friend and mentor. Dantes first major work is the Vita Nuova (New Life), 12931294. This sequence of lyrics, sonnets, and prose narrative describes his love, first earthly, then spiritual, for Beatrice, whom he had first seen as a child of nine and who had died when Dante was twenty-five.

Dante married about 1285, served Florence in battle, and rose to a position of leadership in the bitter factional politics of the city-state. As one of the citys magistrates, he found it necessary to banish leaders of the so-called Black faction, and his friend Cavalcanti, who like Dante was a prominent White. But after the Blacks seized control of Florence in 1301, Dante himself was tried in absentia and was banished from the city on pain of death. He never returned to Florence.

We know little about Dantes life in exile. Legend has it that he studied in Paris, but if so, he returned to Italy, for his last years were spent in Verona and Ravenna. In exile he wrote his Convivio, or Banquet, a kind of poetic compendium of medieval philosophy, as well as a political treatise, Monarchia. He probably began his Comedy (later to be called the Divine Comedy and consisting of three parts, the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso) around 13071308. On a diplomatic mission to Venice in 1321, Dante fell ill, and returned to Ravenna, where he died.

An exciting, vivid Inferno by a translator whose scholarship is impeccable.Chicago magazine

Lovers of the English language will be delighted by this eloquently accomplished enterprise.Book Review Digest

Tough and supple, tender and violent vigorous, vernacular Mandelbaums Dante will stand high among modern translations.The Christian Science Monitor

D ante is an exiled, aggressive, self-righteous, salvation-bent intellectual, humbled only to rise assured and ardent, zealously prophetic, politically messianic, indignant, nervous, muscular, theatrical, energetiche is at once our brother and our engenderer.

We may ponder the divide between the modern and the medieval or profess our distance from Dante, but that profession only masks proximities more intimate than those that link us to antiquity. Even our recovery of the judgmental, ethical aspect of Dante, our anathemas against any Romantic falling prey to (heaven forbid) over-sympathy with Francesca, Farinata, or Ulysses, carries sanctimonious overtones only too easily available to us. Indeed, some contemporary Paraphrasts are more ready to bludgeon homiletically, to damn again the already damned, than even Dante himselfthe greatest of execratorsis. And when we come to the allegorical efforts of the fourfolders, or to our frequent willingness to integrate even Dantes lateral similes into overbearing structures, we have not ventured that far from our selves. Ours, too, is an age of allegoresis; Walter Benjamin is always there, his riches ready to be ransacked or counterfeited. In sum, however more cunning he is than we are, Dante is certainly much nearer to us than is his guide, his governor, his master (Inf. II, 140), Virgil.

Therefore, the task of the modern translator of Dante is much more synonymic and much less metaphorical in kind than the task of the translator of Virgil. Virgil demands more de-selving of the modern translatorso much more that I was slow to hear all his demands.

For I had begun by seeing Virgil from the Dante vantage during the six years I spent translating the Aeneid, a work which often interrupted my translation of the Comedy; I was seeking in the Aeneid what Macrobius (in his Saturnalia V, i, 19) called a style now brief, now full, now dry, now richnow easy, now impetuous. That style (those styles) I reached with relative ease by the third draft. Only in the later drafts did I find a music that lay far beyond what I had first been seeking: measures where the violence of silence and the violence of speech are balanced and appeased in a uniquely Virgilian equilibrium (as in the Palinurus passage at the end of Book Five of the Aeneid).

That equilibrium involves almost unlimited compassion and patient, unjagged breathbut, also, limited curiosity, tight verbal decorum, the most drastic lexical restraints. In my own work as a poet, the release from Virgil produced Chelmaxioms and the forthcoming Savantasse of Montparnasse. And my return, as translator, to Dante, at least in the Inferno, delivered me again to one who is almost wholly given to the violence of speecheven when that violence is directed to talking about the impossibility of talking about the untellable. For Dante is an Aeolus-the-Brusque, a Lord-of-Furibundus-Fuss, the Ur-Imam-of-Impetus. Or, for brutish Scrutinists, who reach for similes among the beasts and not among the gods, he is the lizard that, when it darts from hedge/ to hedge beneath the dog days giant lash,/ seems, if it cross ones path, a lightning flash (Inf. XXV, 7981). However seen, he is surely the swiftest and most succussive of savants, forever rummaging in his vast and versal haversack of soughs and rasps and gusts and harsh and scrannel rhymes (which, in Inf. XXXII, I, he claims he does not haveand then promptly produces). He is seeking those gusts that will most convince us of the credibility of his journey, the accuracy of his record, the trustworthiness of his memory. Mistaking not (Inf. II, 6), he would offer us evidence as undeniable as that of a historian, Livy, of whom we learn, twenty-six cantos later (Inf. XXVIII, 12), that he, too, does not err.

Finally, he would convince us that his are the supreme fictions; and he would do so without contradicting his own claims to truth, because fictio for Dante does not mean pure invention or fantastic creation butas Gioacchino Paparelli has showna poetic composition, constructed with the concourse of rhetoric and music, orwe should sayprosody. And in the construction of such fictions, he is not only a strenuous emulator and intrepid pirate, but a competitor and self-announced victor (Inf. XXV, 94102):

Taccia Lucano omai l dovetocca

del misero Sabello e di Nasidio,

e attenda a udir quel chor si scocca.

Taccia di Cadmo e dAretusa Ovidio,

ch se quello in serpente e quella in fonte

converte poetando, io non lo nvidio;

ch due nature mai a fronte a fronte

non transmut s chamendue le forme

a cambiar lor matera fosser pronte.

Let Lucan now be silent, where he sings

of sad Sabellus and Nasidius,

and wait to hear what flies off from my bow.

Let Ovid now be silent, where he tells

of Cadmus, Arethusa; if his verse

has made of one a serpent, one a fountain,

I do not envy him; he never did

transmute two natures, face to face, so that

both forms were ready to exchange their matter.

That announcement of victory over Ovid and Lucan, who had so collegially welcomed Dante to Limbo, is strategically abetted by Virgils own incitement of Dante in the canto just before, when Dante had sought brief respite from his breathless impetus, a sedentary truce for his triste chair. And Virgils prodding links the journey of the voyager to the journey of the telling of the tale, in

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Inferno»

Look at similar books to Inferno. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Inferno and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.