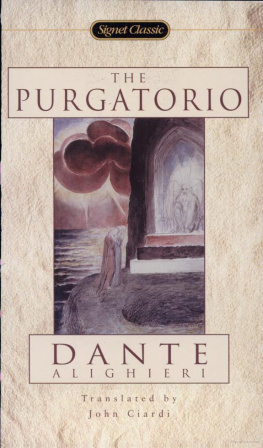

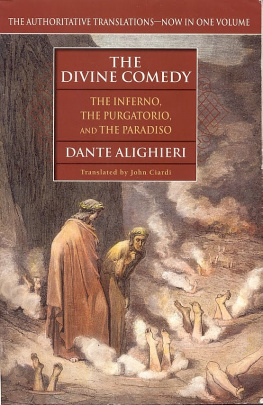

THE DIVINE COMEDY

OF DANTE ALIGHIERI

THE DIVINE COMEDY

OF

DANTE ALIGHIERI

Edited and Translated by

ROBERT M. DURLING

Introduction and Notes by

RONALD L. MARTINEZ

AND ROBERT M. DURLING

Illustrations by

ROBERT TURNER

Volume 1

INFERNO

Oxford University Press

Oxford New York

Athens Auckland Bangkok Bombay

Calcutta Cape Town Dar es Salaam Delhi

Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madras Madrid Melbourne

Mexico City Nairobi Paris Singapore

Taipei Tokyo Toronto

and associated companies in

Berlin Ibadan

Translation copyright 1996 by Robert M. Durling

Introduction and notes copyright 1996

by Ronald L. Martinez and Robert M. Durling

Illustrations copyright 1996 by Robert Turner

First published in 1996 by Oxford University Press, Inc.,

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1997

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dante Alighieri, 12651321.

[Divina commedia. English & Italian]

The divine comedy of Dante Alighieri / edited and translated

by Robert M. Durling ; introduction and notes, Ronald L. Martinez

and Robert M. Durling ; illustrations by Robert Turner,

p. cm. Includes bibliographical references

and index. Contents: v. 1. Inferno.

ISBN-13; /978-0-19-5087444-4

ISBN-10: 0-19-508740-2 / 0-19-508744-5

I. Durling, Robert M. II. Title.

PQ4315.D87 1996

851Mdc20 9512740

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

PREFACE

A Note on the Text and Translation

In this first volume of our projected edition and translation of the Divine Comedy, the text of the Inferno is edited on the basis of the critical edition by Giorgio Petrocchi, sponsored by the Societ Dantesca Italiana, La Commedia secondo lantica vulgata (Copyright 1994, Casa Editriee Le Lettere). We have departed from Petrocchis readings in a number of cases, however, which are discussed under the rubric Textual Variants (page 585), and we have somewhat lightened Petrocchis excessively heavy punctuation and have treated quotations according to American norms.

The translation is prose, as literal as possible, following as closely as practicable the syntax of the original; there is no padding, such as one finds in most verse translations. The closely literal style is a conscious effort to convey in part the nature of Dantes very peculiar Italian, notoriously craggy and difficult even for Italians. Dante is never bland: his vocabulary and syntax push at the limits of the language in virtually every line; there must be some tension, some strain, in any translation that respects the original. While we hope the translation reads well aloud, there is no effort to mirror Dantes sound effectsmeaning and syntax are much more important for our purposes. Latin words and phrases are left untranslated and are explained in the notes; they add an important dimension.

The translation begins a new paragraph at each new terzina; the numbers in the margins are those of the first Italian line of each terzina. This format continually reminds the reader that the original is in verse. It helps approximate the narrative and syntactic rhythm of the original. It calls attention to Dantes frequent, emphatic enjambments between terzinas (the translation keeps the syntax distributed among the terzinas as closely as possible). It is designed to direct the readers attention over to the original, and we believe it facilitates reference to particular lines and words: the reader of the translation can always identify the corresponding Italian, even finding the middle line of a terzina without difficulty.

A Note on the Notes

The notes make no pretension to scholarly completeness, but they are fuller than those found in many current translations; they are designed for the first-time reader of the poem. We have tried to strike a balance among the interests that compete for inclusion: information essential for comprehension, often about historical events and intellectual history; clarification of obscure or difficult passages; and illumination of the complexity of the language, the allusiveness, the intellectual content, and the formal structures of this masterpiece of late Gothic art. We have tried to give some idea of the tradition of commentary on the poem, now roughly 650 years old, and of current developments in Dante studies, many taking place on this side of the Atlantic. We have borrowed freely from earlier commentators and critics. Rather than take the readers hands at every step and tell them exactly what to feel or think, we hope to present some of the materials with which they can build their own views of the poem.

Although fairly extensive, the notes are subject to limitations of space. In countless cases, it simply is not possible to cite differing views or shades of opinion. Usually, when a matter has been the subject of dispute, we call attention to the fact and list in the Bibliography suggestions for further study; but for the most part, we state our own position, with some of its reasons, and pass over in silence the views that we do not accept, many of them recent and set forth with great learning and cogency by their authors, whose indulgence we entreat. Any other approach would have swelled the notes beyond reason; furthermore, we really do not think it would be appropriate, in a commentary meant for readers approaching the poem for the first time, to include the details of scholarly disputes.

But of course your two annotators are human, and some of the details we have excluded from the notes themselves can be found in the Additional Notes at the end of the volume. Here each of us has taken the bit in his teeth on a few subjects dear to his scholarly heart. The titles of these short essays are self-explanatory, we believe; each carries an indication of the part of the poem it concerns or the place in the poem where the issues it discusses have emerged.

Acknowledgments

We have received generous help and encouragement from many friends and colleagues, and it is a pleasure to thank them. Robert McMahon and David Quint read portions of the manuscript at various stages of its evolution and made helpful suggestions. Ken Durling read the entire translation and the introduction; his criticisms were extremely helpful. Sarah Durling was a great help with the introduction. Richard Kay, Edward Peters, and R. A. Shoaf read selected cantos, both translation and commentary, and Charles T. Davis listened to the entire translation on tape; we have adopted many of their suggestions. Ruggero Stefaninis counsel on textual matters was invaluable. Paul Alpers, Nicholas J. Perella, and Regina Psaki read the entire manuscript; they have saved us from a number of errors, and we have adopted a large percentage of their suggestions. We are grateful to Teodolinda Barolini, David L.Jones, and John A. Scott, who caught a number of errors and omissions that we have been able to correct in the third printing. Like those already mentioned, Margaret Brose, Rachel Jacoff, Victoria Kirkham, and Francesco Mazzoni have given us generous encouragement that has been important to us. Nancy Vine Durling has read the manuscript in all its versions; she has caught many mistakes, and her suggestions have been most useful. Mildred Durling, though her eyesight was failing, proofread the entire text of translation and notes and helped us avoid a significant number of errors. We thank Jean-Franois and Sabine Vasseur of Sceaux (France) and Doug Clow of Minneapolis for the cordial hospitality that made possible prolonged meetings of the collaborators. An NEH fellowship for university teachers granted to Ronald L. Martinez for a Dante-related project (1993 1994) contributed significantly to this venture as well. Our greatest debt is to Albert Russell Ascoli, who repeatedly gave both the translation and notes extremely detailed and searching scrutiny. In both, he saved us from errors, recalled us to balance and fairness, and made so many useful suggestions that there is hardly a page that does not reflect his influence. He and our other friends are not to blame, of course, for the errors and shortcomings that may remain. Finally, the patience, forbearance, and active help of our wives, Nancy Vine Durling and Mary Therese Royal de Martinez, have been essential.

Next page