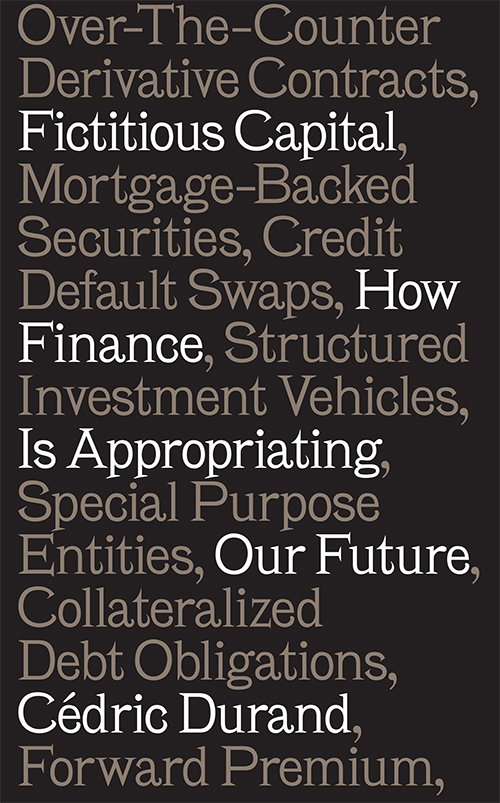

Fictitious Capital

How Finance is

Appropriating Our Future

Cdric Durand

Translated by David Broder

For Jeanne, Loul and Isidore

The translation of this books was supported by the Centre national du livre (CNL).

Cet ouvrage publi dans le cadre du programme daide la publication bnficie du soutien du Ministre des Affaires Etrangres et du Service Culturel de lAmbassade de France reprsent aux Etats-Unis. This work received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States through their publishing assistance program.

English-language edition first published by Verso 2017

Originally published in French as Le capital fictif

Les Prairies ordinaires 2014

Translation David Broder 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-719-6 (PB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-284-5 (HB)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-720-2 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-721-9 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Durand, Cedric, author.

Title: Fictitious capital : how finance is appropriating our future / Cedric Durand ; translated by David Broder.

Other titles: Capital fictif. English

Description: London ; Brooklyn, NY : Verso, 2017. | Originally published in French as Le capital fictif : Les Prairies ordinaies, 2014. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016058500 | ISBN 9781784787196 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Finance. | Capitalism.

Classification: LCC HG173.3 .D8713 2017 | DDC 332dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016058500

Typeset in Minion by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Contents

Data and sources are available online at cedricdurand.eu

This book owes a lot to the unrelenting enthusiasm of Nicolas Vieillescazes and Razmig Keucheyan. All hail Nicolas for his patient editing work! I am also very grateful to David Broder for his meticulous translation and to Versos editors. I would especially like to thank Sebastian Budgen for his sober but constant support.

I carried out my research at the Centre dconomie de Paris Nord on the Villetaneuse campus of the Universit Paris-13, a great place to work. This book would never have seen the light of day if it were not for the countless discussions I had with colleagues there and the helping hand they provided. Here I am particularly thinking of Emmanuel Carr, Benjamin Coriat, David Flacher, Ariane Ghirardello, Dany Lang, Marc Lautier, Antonia Lopez-Villavicencio, Jonathan Marie, Jacques Mazier, Pascal Petit, Dominique Plihon, Nathalie Rey, Sandra Rigot, Francisco Serranito and Julien Vauday. So, too, the dynamic team of doctoral students and young postdocs communing at our lunchtime political-economy seminar: Raquel Almeida Ramos, Flix Boggio, Louison Cahen Fourot, Bruno Carballa, Matteo Cavallaro and Lonard Moulin.

I should make special mention of the generous efforts of Robert Guttman, who took the time to read a first version of this work and discuss it with me in some depth. Tristan Auvray and Cline Baud were also kind enough to read over a draft of the first chapters and share their judicious suggestions. Grgoire Chamayou lent his attentive ear to the development of this book and shared his insights. Sebastian Budgen, Philippe Lg and Bruno Tinel each suggested valuable references. Critical comments by Julien Vercueil, Guillaume Fondu and Eve Chiapello, as well as John Grahls report preceding this English translation, allowed me to refine the text and to clear up certain ambiguities.

My exchanges with Jerry Epstein, William Milberg, Andr Orlan, Riccardo Bellofiore and ric Pineault helped feed my thinking. The arguments developed in the final chapter owe a great deal to my work together with Engelbert Stockhammer and Sbastien Miroudot. The book as a whole also reflects my lively collaboration with Franois Chesnais, Esther Jeffers, Stathis Kouvelakis and Michel Husson, who all did much to inspire it.

I would also like to thank Les Anges for having provided a perfect home for our editorial meetings, before they were cut down by fanatics bullets on 13 November 2015.

One of the most remarkable developments in the rich countries since the 1970s has been the accelerated expansion of financial operations. The 20078 crisis and the long recession in which the world economy has been caught up ever since have brutally exposed the exorbitant economic and social cost of such financialisation. Yet nothing suggests that our societies are on a path to freeing themselves from its grip. While there have been some efforts to exert tighter control over finance, they have not fundamentally challenged the relations that this sector has established with other spheres of the economy over recent decades.

Financialisation is no epiphenomenon. It is a process that gets to the very heart of how contemporary capitalism is organised. Indeed, fictitious capital has taken a central place in the general process of capital accumulation. Incarnated in debts, shares, and a diverse array of financial products whose weight in our economies has considerably increased, this fictitious capital represents claims over wealth that is yet to be produced. Its expansion implies a growing pre-emption of future production.

Fictitious capitals rising power results from substantial transformations in the financial sphere itself, as well as changes that have taken place in its relations with the rest of the social world from the production of goods and services to nature, states and wage-labour. If finance develops according to a dynamic of its own, the hypothesis underpinning this book holds that the boom of fictitious capital is also the product of unresolved social and economic contradictions. As Fernand Braudel eloquently puts it, financialisation is a sign of autumn.

The development of high finance in fourteenth-century Florence responded simultaneously to both the new opportunities for profit to Financialisation, deindustrialisation and social polarisation marched in concert - and they signalled decline.

There are plenty of good reasons to think that contemporary financialisation marks a new autumn. First of all, since the 1980s we have seen a continuous rise in indebtedness in the main rich economies. Even though there are major disparities in the level and composition of the various countries debts, the tendency is a clear and general one. A second striking phenomenon is the fact that the growth of the financial sectors share in the economy translates into a rise in financial profits share of overall profits. A third phenomenon and one that is now well documented is the growth of inequalities. Particularly marked in the Anglo-Saxon countries, this change is apparent in all developed countries, with increased inequality of both incomes and assets.