1. Introduction to Part I

How to begin?

Before we plunge into the unfinished businesses in behavioral economics , it is appropriate to give a refreshing overview of how we got here, that is, the process by which behavioral economics has become a serious competitor to what we call conventional economics (CE). And this is what we deal with in Part I.

To start with, Chap. gives a concise but complete report on the rise and fall of conventional economics . We identify contemporary conventional economics with New Classical Economics , led by people such as Nobel laureate Robert J. Lucas and Thomas Sargent , which has been mainstream throughout the last three decades of the last century and beyond. In this section, we present:

the conceptual pillars of decision-making in conventional economics (i.e. expected discounted utility , rational choice, and rational expectations )

an example of the decision-making process for the leading character of conventional economics , the homo economicus , who has wealth maximization as the sole target, is characterized by consistent preferences and linear time discounting, acts in splendid isolation, and is endowed with complete information and advanced computing capabilities. In particular, after introducing the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), we show the way in which the homo economicus would be supposed to elaborate and implement an asset allocation strategy

analytical evidence of the inadequacy of conventional economics , including EMH, to fit reality, using as a litmus test what happened during the global financial crisis begun in 2007

Chapter is devoted to an overview of the behavioral economics revolution.

We first present the reasons for the emergence and the success of behavioral economics . We then proceed to highlight the features of the behavioral versions of utility and rationality . Utility is no longer just egotistic wealth maximization, but a much wider and complex concept which can also be a function of drivers related to fairness and altruism .

Similarly, behavioral economics questions the conventional view of rationality (based on consistency and coherence ). So to start with, we review the seminal contribution of Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon, who 60 years ago introduced the concepts of bounded rationality and satisficing choices. Then, after giving an account of the major breakthrough implied by the prospect theory developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky , we compare the different tenets of the American and the German schools: for the former, people who use heuristics (mental shortcuts) are plagued by biases and therefore make irrational choices; for the latter, which has its most influential advocate in Gerd Gigerenzer , heuristics are in fact ecologically rational, that is, optimal if environmental factors are taken into account in the decision-making. After describing the way in which real-world people take decisions, we investigate the extent to which the psychological insights introduced by behavioral economics fit reality, using again the global financial crisis as a test bed.

So with Part I of the book, a (hopefully) complete and clear account of how we got here is given.

2. Does Conventional Economics Fit Reality?

2.1 The Rise of New Classical Economics

As it is often the case in history, what is now considered conventional started off as a revolution. Economics is no exception. The revolution began in the early 1970s, especially in the work of Robert Lucas (Nobel Prize winner in 1995) at the University of Chicago, and its name was New Classical Economics.

Given that this book is mainly about behavioral economics and decision-making, in what follows we only give a brief account of the main innovations and tenets of the New Classical paradigm as regards macroeconomics, and focus instead on its basic microeconomic pillars (e.g. utility and rationality ).

The name New Classical was meant to suggest a revival of the Classical Economics, against the then prevailing Keynesian school of thought. In Keynes view, the macroeconomic framework was especially prone to the possible shortage of aggregate demand (the sum of consumption, investment, government expenditure, and net exports), and recessions would in that case readily ensue. In particular, the sequence of events could begin with a fall in private investments. With firms producing less and, given wage stickiness, unable in the short term to cut wages to a level which would be in any case acceptable for workers, the net result is the appearance of involuntary unemployment. In such a situation, an increase in public expenditure is key to boost aggregate demand and bring the system back to equilibrium.

This account of reality seemed quite inconceivable to Lucas and his fellow New Classicals (including famous economists such as Thomas Sargent , Robert J. Barro, and Edward Prescott), as for them price changes would ensure that markets always tend to equilibrium and agents always optimize. If for whatever occasional reasons private investments fell, firms would promptly cut wages to restore profits and workers would accept the best option available (i.e. lower wages) rather than facing unemployment. So, very much as it was the case for the old Classicals, equilibrium is almost always there.

Almost always. Fluctuations in output can indeed occur, and they can be large and/or persistent. In the latter case, the explanation given by New Classicals is structural, as it has to do with productivity/technology change s, which require the entire system to adapt, and of course that may take some time. What is perhaps even more interesting is, however, the interpretation given to non-structural shocks.

As a matter of fact, in order for the New Classicals macroeconomic policies (fiscal and monetary policies) to have any effects on real output, they are subject to one conditionthey must be unanticipated by economic agents. Why? In order to give a satisfactory answer to this question, we should take a step back to what was one of the most successful concepts until the New Classicals showed up on the macroeconomic scene: the Phillips curve.

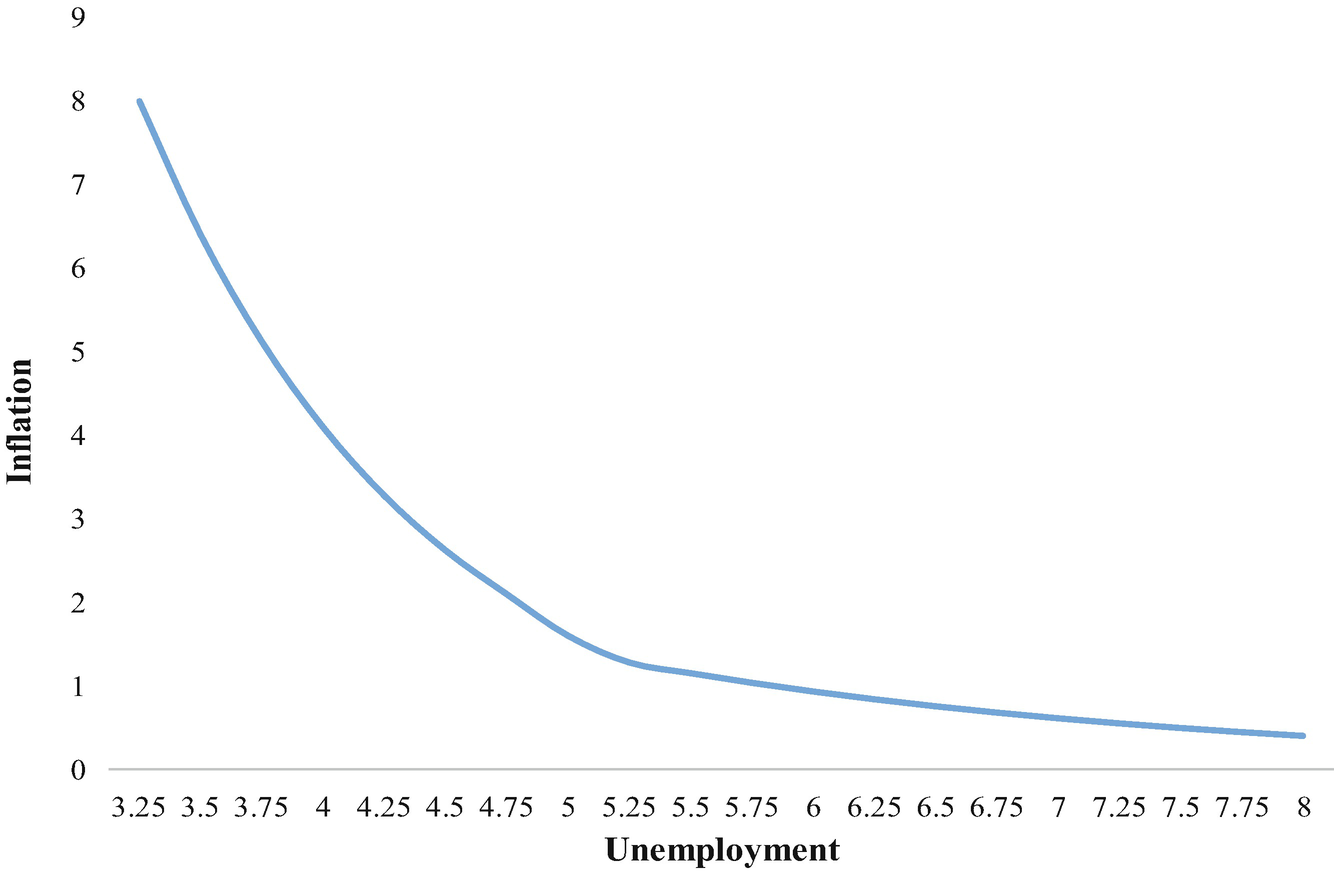

In 1958, A. W. H. Phillips published in the Economica magazine the results of his study of wage inflation and unemployment in the United Kingdom from 1861 to 1957, which highlighted an inverse relationship between the two variables, as visualized in Fig..

Fig. 2.1

Basic Phillips Curve

During the 1960s, this led many to believe that, through the use of monetary policy, governments could choose the combination of inflation and unemployment which was deemed more suitable in any specific circumstance. Unfortunately, that turned out to be not the case. In the US, during the 1970s, the average inflation rate rose by about 4.5% vis--vis the previous decade, and the response of the unemployment rate was not a reduction, but an increase of more than 2%.