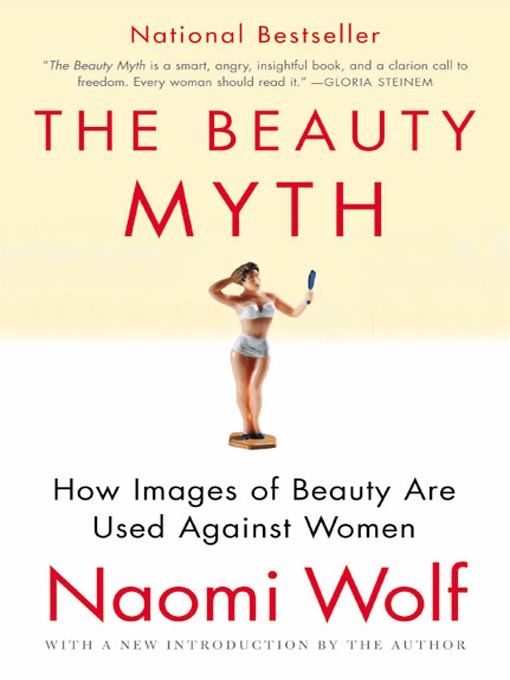

The

Beauty

Myth

How Images of Beauty Are Used

Against Women

Naomi Wolf

It is far more difficult to murder a phantom than a reality.

Virginia Woolf

Product Details

Pub. Date: October 2002

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers

Format: Paperback, 368pp

Sales Rank: 50,245

Series: Harper Perennial

ISBN-13: 9780060512187

ISBN: 0060512180

Edition Description: Reprint

Synopsis

The bestselling classic that redefined our view od the relationship between beauty and femaleidentity.

In today's world, women have more power, legal recognition, and professional success than ever before.

Alongside the evident progress of the women's movement, however, writer and journalist Naomi Wolf is troubled by a different kind of social control, which, she argues, may prove just as restrictive as the traditional image of homemaker and wife. It's the beauty myth, an obsession with physical perfection that traps the modern woman in an endless spiral of hope, self-consciousness, and self-hatred as she tries to fulfill society's impossible definition of "the flawless beauty."

Annotation

In this controversial national bestseller, feminist scholar Naomi Wolf argues that there is one hurdle in the struggle for equality that women have yet to clear--the myth of female beauty. She exposes today's unrealistic standards of female beauty as a destructive form of social control and a reaction against women's increasing status in business and politics.

Publishers Weekly

This valuable study, full of infuriating statistics and examples, documents societal pressure on women to conform to a standard form of beauty. Freelance journalist Wolf cites predominant images that negatively influence women--the wrinkle-free, unnaturally skinny fashion model in advertisements and the curvaceous female in pornography--and questions why women risk their health and endure pain through extreme dieting or plastic surgery to mirror these ideals. She points out that the quest for beauty is not unlike religious or cult behavior: every nuance in appearance is scrutinized by the godlike, watchful eyes of peers, temptation takes the form of food and salvation can be found in diet and beauty aids. Women ar`trained to see themselves as cheap imitations of fashion photographs'' and must learn to recognize and combat these internalized images. Wolf's thoroughly researched and convincing theories encourage rejection of unrealistic goals in favor of a positive self-image. (May)

Contents

iii

When The Beauty Myth was first published, more than ten years ago, I had the chance to hear what must have been thousands of stories. In letters and in person, women confided in me the agonizingly personal struggles they had undergonesome, for as long as they could rememberto claim a self out of what they had instantly recognized as the beauty myth. There was no common thread that united these women in terms of their appearance: women both young and old told me about the fear of aging; slim women and heavy ones spoke of the suffering caused by trying to meet the demands of the thin ideal; black, brown, and white womenwomen who looked like fashion modelsadmitted to knowing, from the time they could first consciously think, that the ideal was someone tall, thin, white, and blond, a face without pores, asymmetry, or flaws, someone wholly perfect, and someone whom they felt, in one way or another, they were not.

I was grateful to have had the good luck to write a book that connected my own experience to that of women everywhereindeed, to the experiences of women in seventeen countries around the world. I was even more grateful for the ways that my readers were using the book.

This book helped me get over my eating disorder, I was often told.

I read magazines differently now. Ive stopped hating my crows feet. For many women, the book was a tool for empowerment. Like sleuths and critics, they were deconstructing their own personal beauty myths.

2 / THE BEAUTY MYTH

While the book was embraced in a variety of ways by readers of many different backgrounds, it also sparked a very heated debate in the public forum. Female TV commentators bristled at my argument that women in television were compensated in relation to their looks and at my claim of a double standard that did not evaluate their male peers on appearance as directly. Right-wing radio hosts commented that, if I had a problem with being expected to live up to ideals of how women should look, there must be something personally wrong with me. Interviewers suggested that my concern about anorexia was simply a misplaced privileged-white-girl psychodrama. And on daytime TV, on show after show, the questions directed to me often became almost hostilevery possibly influenced by the ads that followed them, purchased by the multibillion-dollar dieting industry, making unfounded claims that are now illegal. Frequently, commentators, either deliberately or inadvertently, though always incorrectly, held that I claimed women were wrong to shave their legs or wear lipstick. This is a misunderstanding indeed, for what I support in this book is a womans right to choose what she wants to look like and what she wants to be, rather than obeying what market forces and a multibillion-dollar advertisersing industry dictate.

Overall, though, audiences (more publicly than privately) seemed to feel that questioning beauty ideals was not only unfeminine but almost un-American. For a reader in the twenty-first century this may be hard to believe, but way back in 1991, it was considered quite heretical to challenge or call into question the ideal of beauty that was, at that time, very rigid. We were just coming out of what I have called The Evil Eighties, a time when intense conservatism had become allied with strong antifeminism in our culture, making arguments about feminine ideals seem ill-mannered, even freakish. Reagan had just had his long run of power, the Equal Rights Amendment had run out of steam, womens activists were in retreat, women were being told they couldnt

have it all. As Susan Faludi so aptly showed in her book Backlash, which was published at about the same time as The Beauty Myth, Newsweek was telling women that they had a greater chance of being killed by terrorists than of marrying in mid-career. Feminism had become

the f-word. Women who complained about the beauty myth were assumed to have a personal shortcoming themselves: they must be fat, ugly, incapable of satisfying a man, feminazis, orhorrorslesbians.

The ideal of the timea gaunt, yet full-breasted Caucasian, not often found in naturewas

Introduction / 3

assumed by the mass media, and often by magazine readers and movie watchers as well, to be eternal, transcendent. It seemed important beyond question to try somehow to live up to that ideal.

When I talked to audiences about the epidemic of eating disorders, for instance, or about the dangers of silicone breast implants, I was often given a response straight out of Platos Symposium, the famous dialogue about eternal and unchanging ideals: something like, Women have always suffered for beauty. In short, it was not commonly understood at that time that ideals didnt simply descend from heaven, that they actually came from somewhere and that they served a purpose. That purpose, as I would then explain, was often a financial one, namely to increase the profits of those advertisers whose ad dollars actually drove the media that, in turn, created the ideals. The ideal, I argued, also served a political end. The stronger women were becoming politically, the heavier the ideals of beauty would bear down upon them, mostly in order to distract their energy and undermine their progress.

Next page