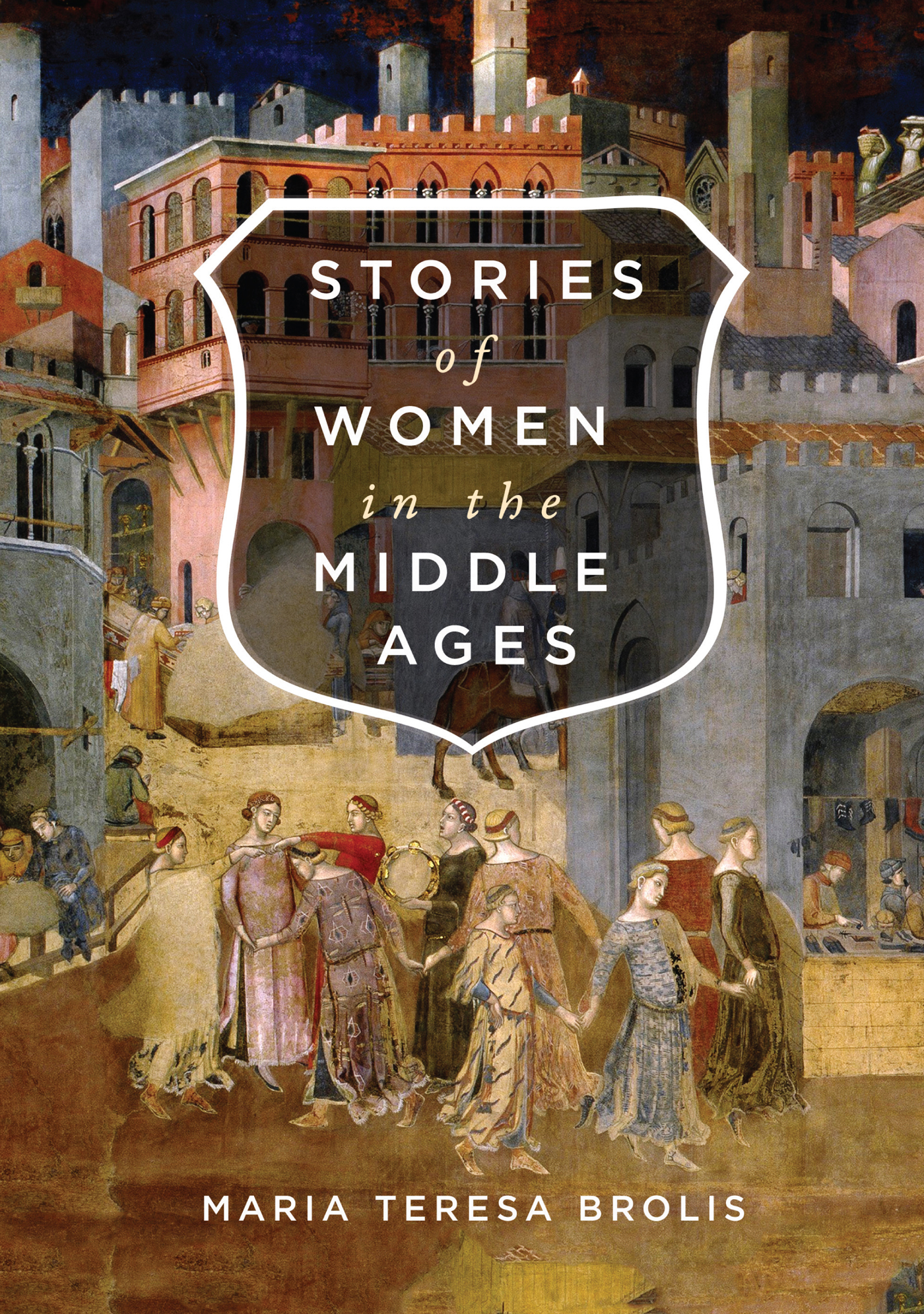

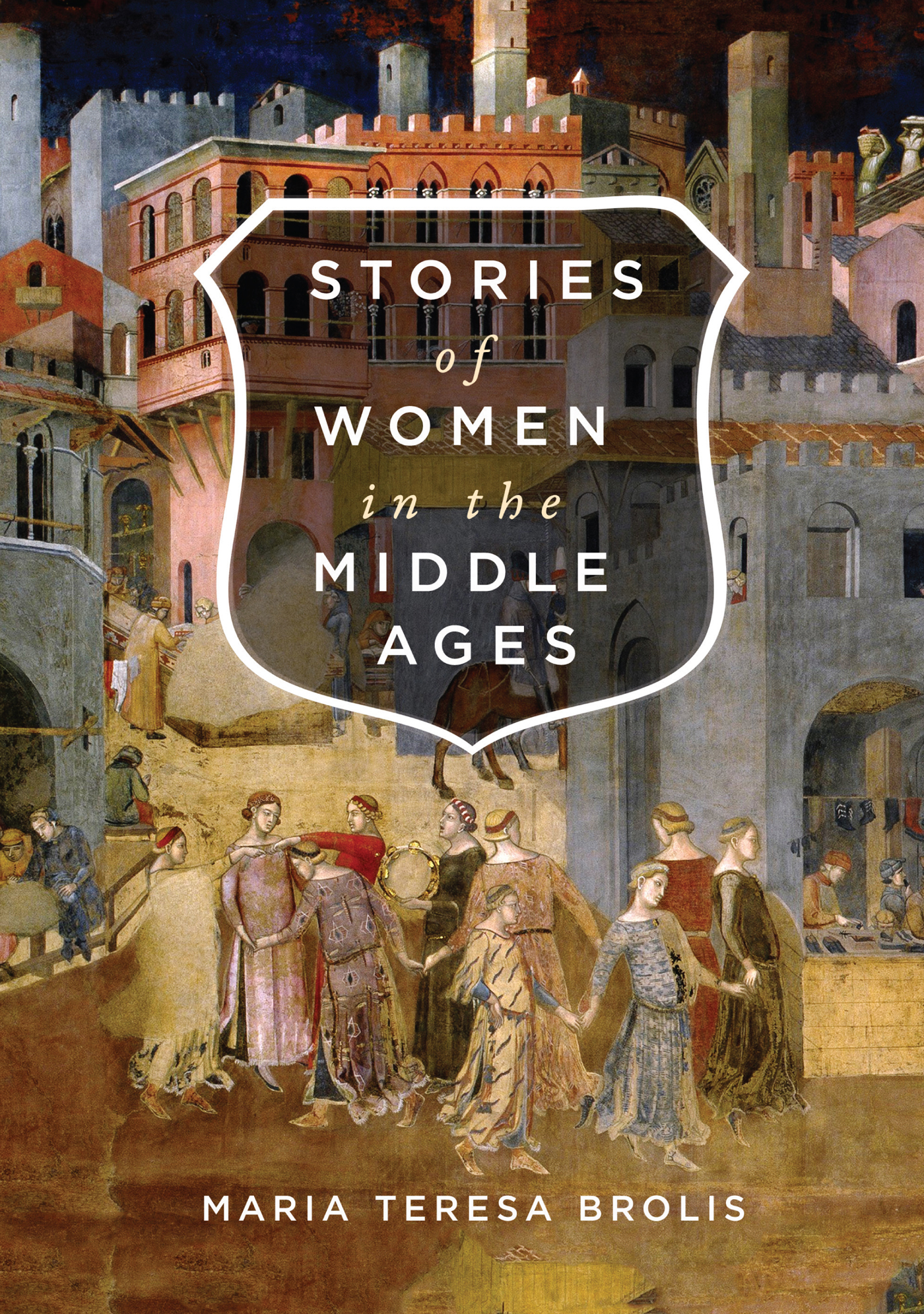

STORIES OF WOMEN IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Maria Teresa Brolis

STORIES of WOMEN in the MIDDLE AGES

FOREWORDS BY FRANCO CARDINI

AND GILES CONSTABLE

Translated by Joyce Myerson

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2018

Originally published in 2016 as Storie di donne nel Medioevo by Societ editrice il Mulino, Bologna

ISBN 978-0-7735-5478-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5479-5 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5614-0 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5615-7 (ePUB)

Legal deposit fourth quarter 2018

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free

The translation of this work has been funded by SEPS Segretariato Europeo per le Pubblicazioni Scientifiche Via Val dAposa 7 40123 Bologna Italy

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. Lan dernier, le Conseil a investi 153 millions de dollars pour mettre de lart dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

Library and Archives Canada

Cataloguing in Publication

Brolis, Maria Teresa, 1959 [Storie di donne nel Medioevo. English]

Stories of women in the Middle Ages / Maria Teresa Brolis ; forewords by Franco Cardini and Giles Constable ; translated by Joyce Myerson.

Translation of: Storie di donne nel Medioevo.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-7735-5478-8 (cloth).

ISBN 978-0-7735-5479-5 (paper).

ISBN 978-0-7735-5614-0 (ePDF).

ISBN 978-0-7735-5615-7 (ePUB)

1. Women Europe Biography.

2. Women History Middle Ages, 5001500. I. Title. II. Title: Storie di donne nel Medioevo. English.

D109.B7613 2018

920.72

C2018-904225-7

C2018-904226-5

Set in 11.5/14.5 Mrs Eaves OT with Agedage SimpleVersal

Book design & typesetting by Garet Markvoort, zijn digital

FOR FRANCO

along with Attilio and Marco

CONTENTS

, by Giles Constable

, by Franco Cardini

FOREWORD TO THE ENGLISH EDITION

This book introduces the reader to a group of sixteen medieval women, of whom eight are well-known and eight are described here as ordinary in the sense of unremarkable. Together they throw light on many aspects of life in the Middle Ages that are relatively unknown as compared with the lives or activities of men. The famous women are Hildegard of Bingen, who is known as an abbess, writer, and musician; Raingarde, the mother of Peter the Venerable and other influential churchmen of the twelfth century; Heloise, the pupil (and lover) of Abelard and subsequently abbess of the Paraclete; Eleanor of Aquitaine, the wife of King Louis VII of France and King Henry II of England and the mother of several other kings; Clare, the founder of the mendicant house of St Damian at Assisi; Bridget of Sweden, the mystic and visionary and founder of the Bridgetine order; Christine of Pizan, whose writings are a valuable source for the intellectual and social history of the late Middle Ages; and Joan of Arc, who is labelled here a rebel.

The eight ordinary women came from the region of Bergamo, an important centre of economic and religious activity, on which the authors research has concentrated. They are mostly of lower social status than the famous group and are sometimes described by historians as invisible because little is known about them, especially their private lives. Here they are identified by their names and by what the author calls their small stories illustrating their occupations and activities. Most of them were poor, but a few were quite prosperous and ran successful businesses. They are identified in the titles with business (Flora), poverty (Agnesina), marriage (Ottebona), religious life (Grazia), fashion (Gigliola), potions (Bettina), care-giving (Margherita), and the road, that is, travel and pilgrimage (Belfiore).

There are many parallels and overlaps between these women, though they came from very different social and economic backgrounds. The importance of religion and religious life is striking. Hildegard, Heloise, Clare, and Grazia were all the founders or heads of religious houses; Bridget and Clare both founded religious orders; Bridget and Belfiore were pilgrims; others spent time as hermits or recluses. The so-called ordinary women, perhaps owing to the nature of the sources, were more concerned than the famous women with practical matters of health, care-giving, and clothing, and their lives, as recorded here, give an idea of the everyday occupations of women. Their stories challenge in many respects the conventional assumptions about medieval women and show that they played a considerable part in religious as well as secular life, serving among other things as preachers and scribes. The theme of aid volunteered by women in diverse ways and places, the author writes, in the home and in the hospital, deserves its very own discussion because it represented one of the most penetrating and powerful aspects, although often a hidden one, of female presence not only in the medieval period, but throughout history.

Many questions that are frequently overlooked or insufficiently studied are thus opened up by this book. Can an historian enter into the house of a medieval woman, the author asks, not only to peek at her furniture and clothes but also to uncover behaviours and even the feelings of individuals? She especially emphasizes that the theme of heresy needs to be re-examined in the light of the most recent historiography and that the presumed or real heterodox inclination often attributed to Bergamesque citizens is configured more as a political alignment than as an actual deeply rooted religious choice. The answers to these and other questions about medieval women, as this book shows, are often yes, though not without limitations. Stories of Women in the Middle Ages opens the door to further wide-ranging research into many questions that need to be studied.

Giles Constable

FOREWORD TO THE ITALIAN EDITION

In comparison to modern or contemporary studies, European medieval studies have been less touched by issues related to gender. Particular themes associated with philosophy have elicited some interest and we acknowledge here the beautiful writing by Michela Pereira dedicated to the theme N Eva, n Maria (Neither Eve nor Mary) as have those studies specifically oriented towards memoir or epistolography, albeit in very different contexts, between Heloise and Alessandra Macinghi Strozzi. In this regard, the by now classic work by Georges Duby, introduced in the relatively distant past, has achieved great significance in framing the issue. In the context of synthesis, we have the propitious work by Edith Ennen, dedicated to women in the Middle Ages, that is about thirty or forty years old. Eight more recent exemplary (in the etymological sense of the word) essays were written thanks to the collaboration between Maria Teresa Beonio Brocchieri Fumagalli, Ferruccio Bertini, and Claudio Leonardi, and issued by the publisher Laterza in 2001, with the title Medioevo al femminile

Next page