GOLD

The Earth series traces the historical significance and cultural history of natural phenomena. Written by experts who are passionate about their subject, titles in the series bring together science, art, literature, mythology, religion and popular culture, exploring and explaining the planet we inhabit in new and exciting ways.

Series editor: Daniel Allen

In the same series

Air Peter Adey

Cave Ralph Crane and Lisa Fletcher

Desert Roslynn D. Haynes

Earthquake Andrew Robinson

Fire Stephen J. Pyne

Flood John Withington

Gold Rebecca Zorach and Michael W. Phillips Jr

Islands Stephen A. Royle

Lightning Derek M. Elsom

Meteorite Maria Golia

Moon Edgar Williams

South Pole Elizabeth Leane

Tsunami Richard Hamblyn

Volcano James Hamilton

Water Veronica Strang

Waterfall Brian J. Hudson

Gold

Rebecca Zorach and

Michael W. Phillips Jr

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448, Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright Rebecca Zorach and Michael W. Phillips Jr 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780236131

CONTENTS

Seated goddess with a child, Hittite Empire, central Anatolia, c. 14th13th century BCE.

Introduction: In Search of Gold

Gold has beguiled humankind from the earliest days of civilization. The most malleable of metals, and one of the most brilliant, it was fashioned early on into artful forms. Often found relatively unadulterated, it did not require sophisticated smelting techniques. Its softness rendered it largely useless for making tools (though modern science has found many uses for it): thus most of its earliest uses were decorative.

The uselessness of gold, and not its inherent beauty or nobility, may also have been what prompted its use as currency. Its relationship to value why it became such a highly prized medium for money is, perhaps, an unanswerable question. Did early human civilizations use gold for money because of qualities they prized in it or do we attribute precious qualities to it, fetishistically, because ancient convention, for reasons now obscured, decrees that we use it for money? It is also notable that throughout history gold has been used to represent the antithesis of true value in critiques of wealth and idolatry almost as much as it has compelled admiration. The questions posed by the human desire for gold are central questions about value itself and about meaning.

Gold is an element, one of the heavy metals. Unlike lighter elements, gold cannot be created by fusion within stars. Scientists now believe the gold in the universe likely came from collisions between dying stars (supernovas). The meteorite collisions that produced the gold humans mine took place a very long time ago. Gold deposits in the Witwatersrand region of South Africa the origin of 40 per cent of the gold ever mined from the earth are dated to 3 billion years old, 1.5 billion years younger than the earth. Compared to these events, any human encounter with the metal is quite recent. But humans have used gold since the dawn of our own history. It is found on every continent, and was among the first metals prehistoric peoples mined and used.

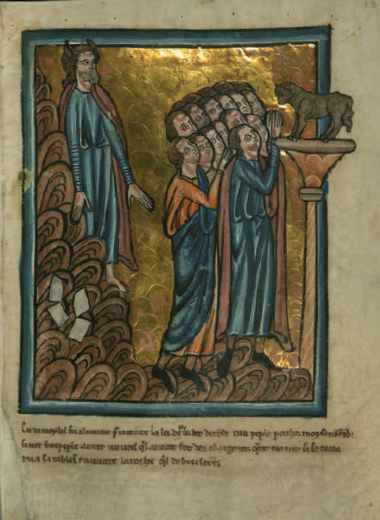

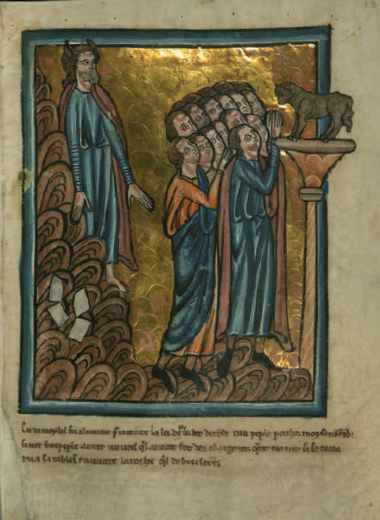

| The Israelites worship the Golden Calf, by the English illuminator William de Brailes, c. 1250, ink, pigment and gold on parchment. |

Primary deposits of gold are found as particles or in veins lodged in minerals like basalt and granite and in rock formations called turbidites (sedimentary rock layers formed through the action of ancient oceans). The combination of gold and the rock that hosts it is called an ore; the gold contained in the rock is also called lode gold. Often, gold is found together with quartz and iron pyrite (also known as fools gold), and typically as a natural alloy with silver or copper. Nuggets of pure gold may be the result of the activity of bacteria. Scientists have studied two in particular, Delftia acidovorans and Cupriavidus metallidurans, which have a genetic resistance to the toxicity of heavy metals. They have been shown to dissolve gold into nanoparticles that can travel through sediment and may collect as nuggets.

Miners and their wives posing with the finders of the Welcome Stranger Nugget, Richard Oates, John Deason and his wife, albumen silver carte-de-visite photograph, 1869.

The shiny nuggets we associate with the discovery of gold are typically found in placer deposits, dense concentrations of particles of gold eroded from rocks and deposited in the banks of rivers and streams. (Placer is a Spanish word for a sandbank.) The biggest nuggets, however, have been found in underground mines. The one that is probably the biggest ever found (at a refined weight of 71.018 kg), the Welcome Stranger, was found in Australia in 1858 and melted down in London in 1859. The Cana nugget, found in Para, Brazil, in 1983, may have been part of a nugget even larger than the Welcome Stranger, and is today the largest nugget in existence, containing 52.332 kg of gold.

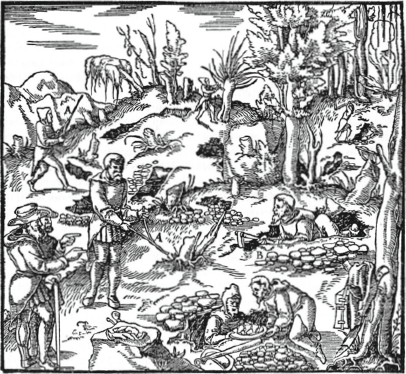

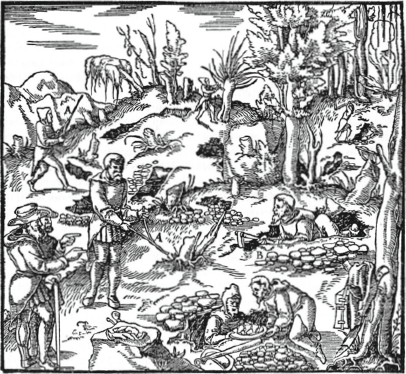

| Woodcut image of dowsing, from Agricola, De re metallica (1556). |

Gold-seekers have used some extraordinary techniques to discover hidden gold deposits, from dowsing (using specially shaped sticks to try to identify magnetic impulses from buried gold) to gold-dreaming (treasure hunters in nineteenth-century Ireland reported success upon following information given to them in dreams), to the modern use of botanical indicators (horsetail, for example, can assimilate large quantities of gold and serves as an indicator of high soil concentrations of the metal). But historically most attempts to extract gold have originated with a chance find of a flake or nugget in a body of water, as in the case of James W. Marshalls discovery of gold in the tailrace or sluice of a sawmill he was building which sparked the California Gold Rush. Indeed, the earliest gold-seekers of the chalcolithic period likely used placer mining techniques one would recognize from a film about the California Gold Rush rinsing gravel with water to uncover gold flakes and nuggets. Panning for gold is a version of this technique: sifting gravel in a large pan filled with water until the gold, which is denser than other substances, settles to the bottom. On a larger scale, one can shovel gravel into sluice boxes or rockers; on an even larger scale, one can use pressurized jets of water to dislodge rock or sediment and wash the slurry into sluice boxes.