An old woman sits in front of a dressing table mirror while two younger women put feathers in her hair, 17th century, etching.

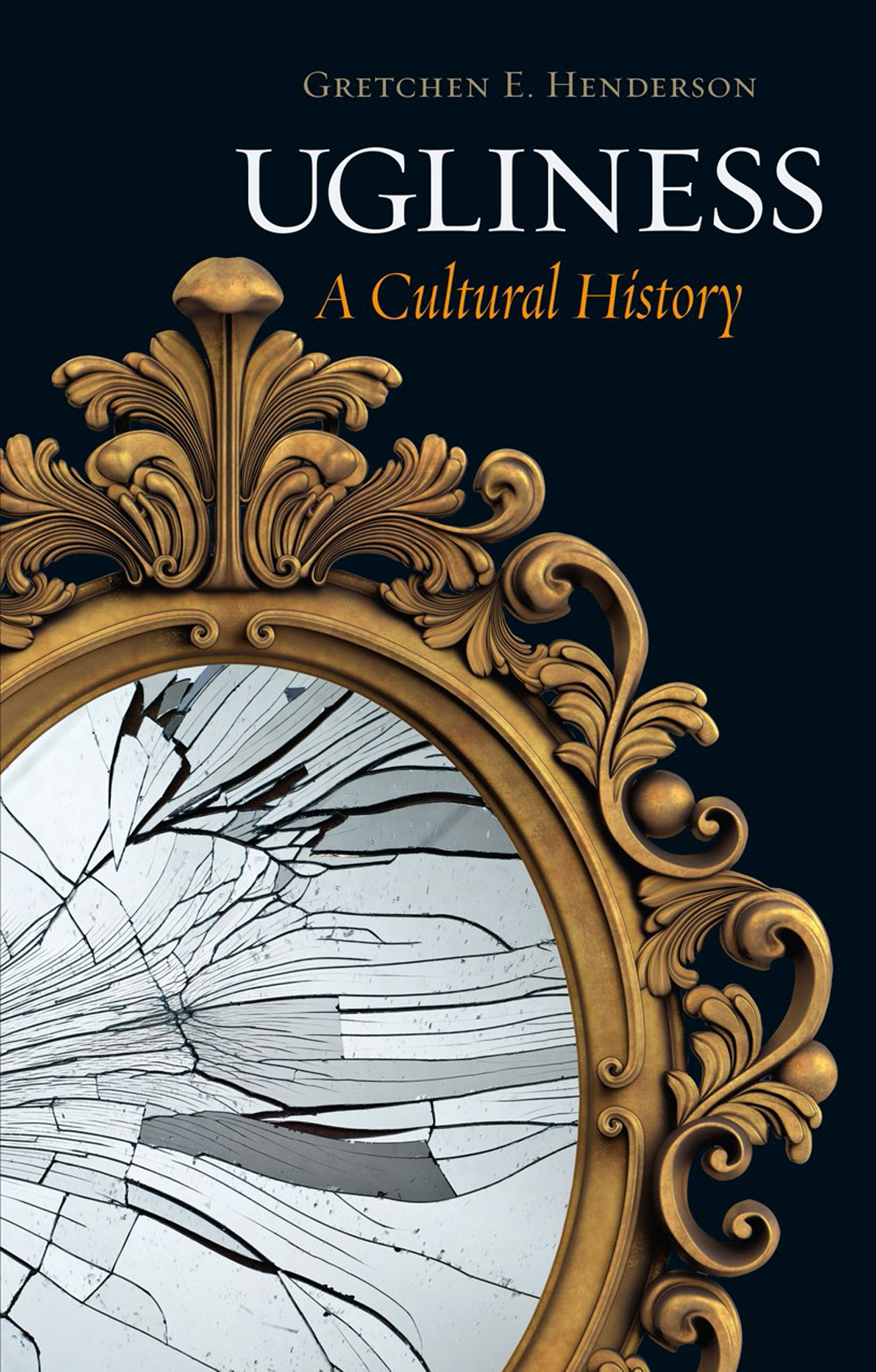

Introduction: Pretty Ugly: A Question of Culture

U glydolls, Ugly Americans, Uglies, the Pretty Ugly Club: from contemporary television to toys to literature to music, recent years have witnessed rising interest in ugliness. As Sarah Kershaw titled an article not long ago in the New York Times: Move Over, My Pretty, Ugly Is Here. But the concept has a much longer lineage that haunts our cultural imagination: from medieval grotesque gargoyles to Mary Shelleys monster cobbled from corpses; from Hans Christian Andersens tale about a mud-coloured duckling to the Nazi Exhibition of Degenerate Art; from the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi to Brutalist architecture. Ugliness has long posed a challenge to aesthetics and taste, engaging and enraging philosophers, complicating questions about the human condition and the wider world in which we live and interact.

Ugliness: A Cultural History sets out to reinhabit varied cultural moments that reveal changing concepts of ugliness. Rather than stuff these connotations into a singular and sagging definition, I aim to dig up ugly synonyms across history to reanimate and complicate the words etymologic roots: to be feared or dreaded. Recent appropriations push ugliness into new terrain, treating the subject in positive rather than negative terms, naturalized and even banal. Art galleries from London to New York herald ugly exhibits; children cuddle Uglydolls; an annual festival in Italy celebrates ugliness through a festa dei brutti. While the concept continues to grow from its dreaded roots, these appropriations help us to re-view the world from shifting perspectives including the perspective of the ugly object making more apparent the existence and contingency of what is to be feared and of what not to fear at all.

If we follow Aristotles or Albertis belief that a beautiful object bears coherence in totality (a sense of ideal form with a distinct boundary between itself and the world), then ugliness and its ilk carry something more ambiguous and less coherent, excessive or in a state of ruin. Like this linguistic evolution, my own sense of the definition keeps changing, particularly as I traverse historical sources on the subject.

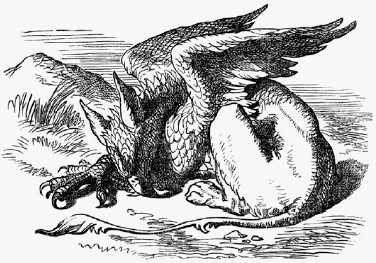

Never heard of uglifying! cries the Gryphon in Alices Adventures in Wonderland. You know what to beautify is, I suppose? Unable to quantify ugliness, Umberto Eco claims:

Beauty is, in some ways, boring. Even if its concept changes through the ages, nevertheless a beautiful object must always follow certain rules... Ugliness is unpredictable and offers an infinite range of possibilities. Beauty is finite. Ugliness is infinite, like God.

Illustration of the Gryphon by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll, Alices Adventures in Wonderland (1872).

Crispin Sartwell has attempted to find the equivalent word for beauty in six languages and discovered different concepts in English, Greek, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Navajo and Japanese the last of which, wabi-sabi, he defines as the beauty of the withered, weathered, tarnished, scarred, intimate, coarse, earthly, evanescent, tentative, ephemeral. These adjectives might fall into the realm of ugly in other cultural contexts, yet in Japan, they are deemed beautiful.

Rather than mere binaries, ugliness and beauty seem to function more like binary stars, which fall into one anothers gravity and orbit each other while being constellated with many other stars. By constellating, even blurring, the boundaries between ugliness and beauty, I am not attempting to characterize every star in the ugly universe as beautiful, or vice versa. If so, both words would lose their meaning, in a kind of hoarding where detritus is as valued as diamonds. The two concepts inhabit a wider grey space. Shadowed by changing cultural appropriations, both definitions keep shifting, through not only accumulation but negation. As architectural theorist Mark Cousins writes, all speculation about ugliness travels through the realm of what it is not. If ugliness provokes a shift beyond comfort and stasis, it arguably incites change.

| Helen Stratton, illustration of the old woman and the Ugly Duckling for Hans Christian Andersen, Tales from Hans Andersen (1896). |

In his treatise on esthetik des Hsslichen (Aesthetics of Ugliness, 1853), Karl Rosenkranz described how ugliness is not merely the inverse of beauty or a negative entity but rather a condition in itself. As ugly and related terms have evolved over history, their mutable usages push us to occupy not only the duality of object and subject but the space between. As the meaning of ugly shifts and crosses bounds, it arguably breaks down the line between us and them. Ugliness provokes us to re-evaluate cultural borders, including bodies that have been included and excluded, to question our own place in the mix.

My interest in ugliness arose from intersections in the fields of art history, literature and disability studies. While researching the concept of deformity, I happened upon an obscure eighteenth-century