STERLING SIGNATURE and the distinctive Sterling Signature logo

are trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

2011 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Text by Hazel Davies

Paper crafts by Michael Flannery

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7875-9

Sterling eBook ISBN: 978-1-4027-8930-4

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and

corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales Department

at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

Contents

B UTTERFLIES AND MOTHS have fascinated people for centuries. Their bright colors, varied wing shapes, and endless patterns capture the imagination; they are the stuff of myth and folklore. The ancient Greek word for butterfly is psuche, which in English translates to psyche or souland indeed butterflies are spiritual symbols in many cultures. In the Middle Ages they were thought to be fairies intent on stealing milk and butter. The Old English name buttorfleoge comes from the words for butter and fly, which perhaps arose from that notion and eventually led to the modern term butterfly. Or the name may have simply come from the many yellow sulphur butterflies (family Pieridae) seen flying in the spring that looked like butter-colored flies.

Butterfly collecting was a very popular pastime in Europe during the 1800s. People of all classes joined societies and attended field trips in pursuit of knowledge and specimens. Wealthy people, with both the time and money to indulge their obsession, were able to accumulate huge collections by employing professional collectors and funding expeditions to capture exotic specimens in far-off lands. Lionel Walter Rothschild (later to become Lord Rothschild) was born into a distinguished banking family, but his real passion lay in natural history. In 1892, he opened his own museum in Tring, England, which housed the largest private zoological collection in the worldincluding 2.25 million butterflies and moths. Rothschilds specimens now form the core of the collection at the Natural History Museum, London.

More recently, butterfly watching, or butterflying, has become a popular hobby with numerous clubs and festivals devoted to the activity. People equipped with binoculars, field guides, and cameras (to collect photographs rather than specimens) make regular field trips in search of species on their checklists. Tour companies lead butterfly-focused trips to hotspots like Costa Rica and the Amazon. But you dont need to travel far from home to enjoy these wonderfully dazzling creatures. As more and more butterfly conservatories open around the world, exotic species are practically being brought to your doorstep.

A sulphur butterfly (Phoebis philea)

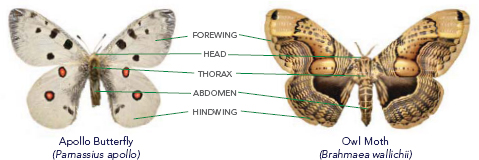

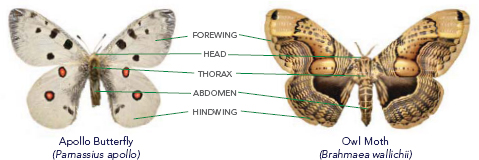

B UTTERFLIES AND MOTHS are insects, and like all insects, their bodies consist of three major segments: a head, a thorax, and an abdomen. They have six jointed legs and four wings attached to the thorax. The soft body is encased in an exoskeleton made of a horny polysaccharide material called chitin. What makes butterflies and moths unique among insects are the scales that cover their wings and bodies. Scales are modified hairs that form an overlapping pattern on the wings like a tiled roof. Each scale is a single color. The colors may result from internal pigments, or they may be due to a specialized surface structure on the scale, reflecting the light we see thus giving the wings a shiny, iridescent quality.

Butterfly wing scales at 100x magnification

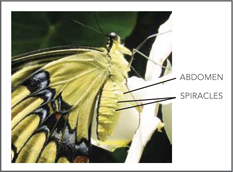

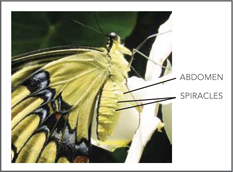

Butterflies and moths do not have a closed circulation system of veins and arteries like humans; instead, a liquid called hemolymph fills the body cavity and is moved around by a tubular heart. A simple nervous system runs throughout the entire body and controls motion, digestion, circulation of hemolymph, and reproduction. There are no lungs in butterflies and moths; they breathe through holes in their exoskeleton called spiracles. Each body segment bears a pair of spiraclesone on each side of the body that look like tiny pores along the side of the thorax and abdomen. The spiracles connect to a network of tracheae that distribute oxygen throughout the body.

Insects are ectothermic, or cold-blooded; they cannot maintain a constant body temperature on their own. Since butterflies need a body temperature between 77111 degrees Fahrenheit (25 44 degrees Celsius) to be able to fly, they warm up their flight muscles by basking with their wings outstretched in a sunny spot. Their wings absorb heat and radiate it into the air around their bodies. If a butterfly gets too hot, it finds a shady area or folds its wings closed and stands with them parallel to the suns rays. Moths cannot bask at night, so instead they appear to shiver. In actuality, they are vibrating their flight muscles to generate heat.

Just like humans, butterflies and moths experience the world around them through five senses. They see through compound eyes made up of thousands of individual facets, called ommatidia, which can detect motion very well and see a wide spectrum of colors, including ultraviolet. But their eyes do not focus clearly, and they cannot see details from a distance.

A simple membrane that acts like an eardrum by detecting vibrations is found in many species of moths and some butterflies. Moths flying at night use this eardrum to detect the echolocation cries of predatory bats. Male Cracker butterflies (Hamadryas spp.) can communicate with one another through a surprisingly loud cracking sound made by their wings, which is thought to be a territorial warning.

Butterflies and moths detect odors through chemoreceptors located on their antennae. These sense organs are very powerful; some male moths can detect the scent, or pheromone, of a female moth from a distance of over a mile.

Taste receptors are located on their feet, or tarsi, and on the tip of the proboscis.

Butterflies and moths have hairs called tactile setae over most of their body. The setae are attached to nerve cells, which relay information about the hairs movement. This helps the insect detect the position of one body part in relation to another.

All plants and animals are named and classified using the binomial system put forth by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. Two Latin names, the first for the genus and the second for the species, are assigned to each organism. Butterflies and moths belong to the huge group, or class, called Insecta. The class is divided into smaller groups, termed orders, based on unique characteristics. The bodies of butterflies and moths are completely covered in scales. Because of this characteristic, they are placed in the order Lepidopterafrom the Ancient Greek words