Editor: Sasha Lilley

Spectre is a series of penetrating and indispensable works of, and about, radical political economy. Spectre lays bare the dark underbelly of politics and economics, publishing outstanding and contrarian perspectives on the maelstrom of capitaland emancipatory alternativesin crisis. The companion Spectre Classics imprint unearths essential works of radical history, political economy, theory and practice, to illuminate the present with brilliant, yet unjustly neglected, ideas from the past.

Spectre

Greg Albo, Sam Gindin, and Leo Panitch, In and Out of Crisis: The Global Financial Meltdown and Left Alternatives

David McNally, Global Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance

Sasha Lilley, Capital and Its Discontents: Conversations with Radical Thinkers in a Time of Tumult

Sasha Lilley, David McNally, Eddie Yuen, and James Davis, Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth

Peter Linebaugh, Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance

Spectre Classics

E.P. Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary

Victor Serge, Men in Prison

Victor Serge, Birth of Our Power

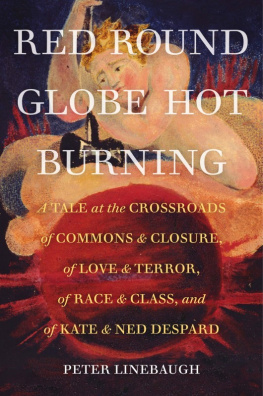

Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance

Peter Linebaugh

Peter Linebaugh 2014

This edition PM Press 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-60486-747-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013911523

Cover by John Yates/Stealworks

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com

To Kate and Riley, sisters

Contents

Acknowledgments

I thank and acknowledge Celia Chazelle, an editor of Why the Middle Ages Matter: Medieval Light on Modern Injustice (London: Routledge, 2012) for whom I wrote the essay on Wat Tyler.

I thank and acknowledge Amy Chazkel, editor of special issue on the enclosures of the Radical History Review 108 (Fall 2010), for which I wrote Enclosures from the Bottom Up.

I thank Jeffrey St. Clair and the late Alexander Cockburn of CounterPunch, who first published The Commons, the Castle, the Witch, and the Lynx (2009).

I thank the Ireland Institutes The Republic, where I published The Red-Crested Bird and Black Duck (Spring-Summer 2001).

I thank especially Sasha Lilley for commissioning my introduction to the PM Press edition of E.P. Thompsons biography of William Morris and for her help with it.

I thank Verso Books for the republication of my introduction to its Thomas Paine anthology (2009).

I thank Ana Mendez de Andes of Traficantes de Sueos for The City and the Commons, first presented at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid (2013).

I thank the genial Barry Maxwell of the Institute of Comparative Modernities at Cornell University, who organized two important conferences, one on primitive accumulation (2004) and the other on globalizing anarchism (2012), which produced a scholarly commons.

I thank Silke Helfrich and David Bollier for their active inter-commoning.

I thank Gustavo Esteva, Kevin Whelan, Staughton Lynd, Manuel Yang, John Roosa, Marcus Rediker, Silvia Federici, Dan Coughlin, and Dave Riker for friendly inspiration.

Some of the essays contain specific acknowledgments. Thus for Karl Marx, the Theft of Wood, and Working-Class Composition (1976) I thanked Bobby Scollard, Gene Mason, and Monty Neill, all of the New England Prisoners Association.

I thank Alan Habercomrade, neighbor, and palfor commissioning two pieces.

I thank a group of artists, scholars, and archivists at the Blue Mountain Center in the Adirondacks, including Malav Kanuga and George Caffentzis for help with The Invisibility of the Commons.

I thank Iain Boal of Birkbeck College, University of London, for publishing Ned Ludd & Queen Mab and for road trips to the serpent mound in Chillicothe, Ohio, and to the Brecklands, Norfolk, UK.

For all-round encouragement I thank the anti-enclosing, thief-stopping comrades of Ypsilanti Occupy, Jeff Clark and Quemadura, and for anti-war leadership I thank Libby Hunter, Gordon Bigelow, and the Liberty Street Agitators.

I thank Ramsey Kanaan and Sasha Lilley, my PM Press editors, who have been unfailingly prompt, helpful, and encouraging.

I thank Riley Linebaugh for clarifying discussions, helpful suggestions, and joie de vivre. Finally, I offer deep and tender thanks to my compaera, Michaela Brennan, with whom Ive shared these journeys arm in arm.

Introduction

WOBBLY SOAP-BOXERS WERE ABLE TO GET A CROWDS ATTENTION WITH THE SIMPLE street cry, Stop, thief! With the crowds attention thereby obtained, the soap-boxer continued, Ive been robbed. Ive been robbed by the capitalist system and then into his spiel.

I wrote Stop, Thief! to join the alarm against neoliberalism which steals our land, our lives, and the labors of those preceding us.

The fifteen essays were written against enclosure, the process of privatization, closing off, and fencing in. Enclosure is the historical antonym and nemesis of the commons. Stop, Thief! is intended to help put an end to legal fibs and ideological fables that cover up truths such as, for example, that the enclosers are thieves who make laws which say that we are the thieves! A well-known but anonymous English poem expresses this truth which my essays merely elaborate.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

Most every student of the commons comes across this quatrain sooner or later. The charm of the lines arises from the crime against the goose, as if it were a sound bite from the Animal Liberation Front. But with a moments thought we understand that the key term is not goose but the common.

There are two thoughts. The first one is true enough, and a generation of English social historians have done much to reestablish it, that imprisonment grew with enclosures replacing the old chastisements, like the stocks. A massive prison construction program accompanied the enclosure of agricultural production. In addition this scholarly literature established that the man or woman locked up had been a commoner, not a villain at all.

The second thought is the thought of expropriation or privatization. It says that a greater but nameless villain has stolen the common. Fences, ditches, walls, hedges, razor wire, and the like demark the boundaries of private property. They were built lawfully by Act of Parliament when Parliament was composed exclusively of landlords. They called it improvement, and today they call it development or progress. Just as the emperor has no clothes, these words are naked of meaning.

The greater villains aim to take land. In the Ohio valley, in Bengal, in the English midlands, in west Africa, in Chiapas, in Borneo, Indonesia. Why? They want whats underneath: gold, coal, oil, iron, what have you. They also create the proletariat, i.e., you! This taking, this expropriating the common, is a process of war, foreign and domestic.