The Rhetoric of Reaction

By the Same Author

National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (1945)

The Strategy of Economic Development (1958)

Journeys Toward Progress:

Studies of Economic Policy-Making in Latin America (1963)

Development Projects Observed (1967)

Exit, Voice, and Loyalty:

Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (1970)

A Bias for Hope:

Essays on Development and Latin America (1971)

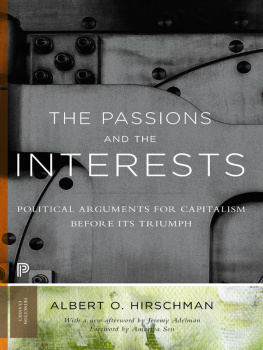

The Passions and the Interests:

Political Arguments for Capitalism before Its Triumph (1977)

Essays in Trespassing:

Economics to Politics and Beyond (1981)

Shifting Involvements:

Private Interest and Public Action (1982)

Getting Ahead Collectively:

Grassroots Experiences in Latin America (1984)

Rival Views of Market Society and Other Recent Essays (1986)

ALBERT O. HIRSCHMAN

The Rhetoric of Reaction

Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

Copyright 1991 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hirschman, Albert O.

The rhetoric of reaction : perversity, futility, jeopardy / Albert O. Hirschman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-674-76868-X

1. ConservatismHistory. 2. Poor lawsHistory. 3. SuffrageHistory. 4. Welfare stateHistory. I. Title.

JA83.H54 1991 90-2361

320.5209dc20 CIP

This book has been digitally reprinted. The content remains identical to that of previous printings.

To Sarah,

my first reader and critic

for fifty years

Contents

How does a person get to be that way? In a New Yorker short story by Jamaica Kincaid (June 26, 1989, pp. 3238), that question is asked repeatedly and insistently by a young woman from the Caribbean about her employer, Mariahan effusive, excessively friendly, and somewhat obnoxious North American mother of four children. In the context, differences of social and racial background supply much of the answer. Yet, as I read the story, it struck me that Kincaids questiona concern over the massive, stubborn, and exasperating otherness of othersis at the core of the present book.

The unsettling experience of being shut off, not just from the opinions, but from the entire life experience of large numbers of ones contemporaries is actually typical of modern democratic societies. In these days of universal celebration of the democratic model, it may seem churlish to dwell on deficiencies in the functioning of Western democracies. But it is precisely the spectacular and exhilarating crumbling of certain walls that calls attention to those that remain intact or to rifts that deepen. Among them there is one that can frequently be found in the more advanced democracies: the systematic lack of communication between groups of citizens, such as liberals and conservatives, progressives and reactionaries. The resulting separateness of these large groups from one another seems more worrisome to me than the isolation of anomic individuals in mass society of which sociologists have made so much.

Curiously, the very stability and proper functioning of a well-ordered democratic society depend on its citizens arraying themselves in a few major (ideally two) clearly defined groups holding different opinions on basic policy issues. It can easily happen then that these groups become walled off from each otherin this sense democracy continuously generates its own walls. As the process feeds on itself, each group will at some point ask about the other, in utter puzzlement and often with mutual revulsion, How did they get to be that way?

In the mid-eighties, when this study was begun, that was certainly how many liberals in the United States, including myself, looked at the ascendant and triumphant conservative and neoconservative movement. One reaction to this state of affairs was to inquire into the conservative mind or personality. But this sort of head-on and allegedly in-depth attack seemed unpromising to me: it would widen the rift and lead, moreover, to an undue fascination with a demonized adversary. Hence my decision to attempt a cool examination of surface phenomena: discourse, arguments, rhetoric, historically and analytically considered. In the process it would emerge that discourse is shaped, not so much by fundamental personality traits, but simply by the imperatives of argument, almost regardless of the desires, character, or convictions of the participants. Exposing these servitudes might actually help to loosen them and thus modify the discourse and restore communication.

That the procedure I have followed possesses such virtues is perhaps demonstrated by the way in which my analysis of reactionary rhetoric veers around, toward the end of the book, to encompass the liberal or progressive varietysomewhat to my own surprise.

In 1985, not long after the reelection of Ronald Reagan, the Ford Foundation launched an ambitious enterprise. Motivated no doubt by concern over mounting neoconservative critiques of social security and other social welfare programs, the Foundation decided to bring together a group of citizens who, after due deliberation and inspection of the best available research, would adopt an authoritative statement on the issues that were currently being discussed under the label The Crisis of the Welfare State.

In a magisterial opening statement, Ralf Dahrendorf (a member, like myself, of the group that had been assembled) placed the topic that was to be the subject of our discussions in its historical context by recalling a famous 1949 lecture by the English sociologist T. H. Marshall on the development of citizenship in the West.eighteenth century witnessed the major battles for the institution of civil citizenshipfrom freedom of speech, thought, and religion to the right to even-handed justice and other aspects of individual freedom or, roughly, the Rights of Men of the natural law doctrine and of the American and French Revolutions. In the course of the nineteenth century, it was the political aspect of citizenship, that is, the right of citizens to participate in the exercise of political power, that made major strides as the right to vote was extended to ever-larger groups. Finally, the rise of the Welfare State in the twentieth century extended the concept of citizenship to the social and economic sphere, by recognizing that minimal conditions of education, health, economic well-being, and security are basic to the life of a civilized being as well as to meaningful exercise of the civil and political attributes of citizenship.

When Marshall painted this magnificent and confident canvas of staged progress, the third battle for the assertion of citizenship rights, the one being waged on the social and economic terrain, seemed to be well on its way to being won, particularly in the Labour Party-ruled, social-security-conscious England of the immediate postwar period. Thirty-five years later, Dahrendorf could point out that Marshall had been overly optimistic on that score and that the notion of the socioeconomic dimension of citizenship as a natural and desirable complement of the civil and political dimensions had run into considerable difficulty and opposition and now stood in need of substantial rethinking.

Marshalls three-fold, three-century scheme conferred an august historical perspective on the groups task and provided an excellent jumping-off point for its deliberations. On reflection, however, it seemed to me that Dah rendorf had not gone far enough in his critique. Is it not true that not just the last but each and every one of Marshalls three progressive thrusts has been followed by ideological counterthrusts of extraordinary force? And have not these counterthrusts been at the origin of convulsive social and political struggles often leading to setbacks for the intended progressive programs as well as to much human suffering and misery? The backlash so far experienced by the Welfare State may in fact be rather mild in comparison with the earlier onslaughts and conflicts that followed upon the assertion of individual freedoms in the eighteenth century or upon the broadening of political participation in the nineteenth.

Next page