The

Mother

of All

Questions

Rebecca Solnit

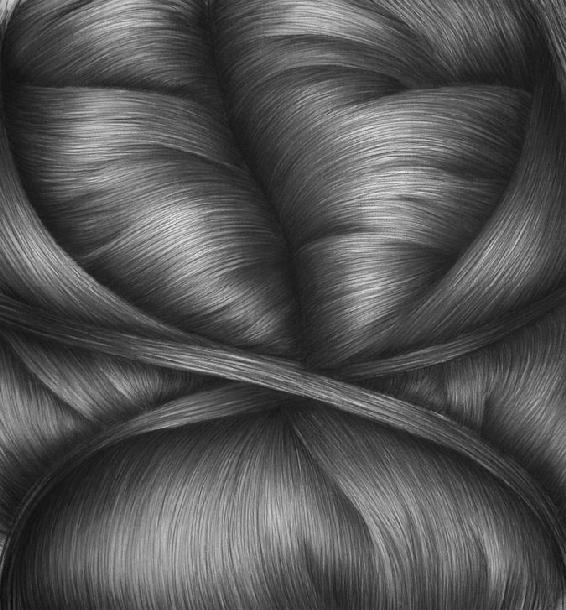

Images by Paz de la Calzada

Haymarket Books

Chicago, Illinois

2017 Rebecca Solnit

Interior images Paz de la Calzada

Haymarket Books

PO Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

info@haymarketbooks.org

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-720-4

Trade distribution:

In the US, through Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases by organizations and institutions.

Please contact Haymarket Books for more information at 773-583-7884 or info@haymarketbooks.org.

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and the Wallace Action Fund.

Cover design by Abby Weintraub.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Contents

In hope we keep going

with love for the newcomers

and their beautiful noise:

Atlas

Ella and Maya

Isaac and Martin

Berkeley

Brooke, Dylan, and Solomon,

Daisy and Jake;

and thanks to the readers

and to the hellraisers

Introduction

The longest and newest essay in this book is about silence, and I began it thinking I was writing about the many ways women are silenced. I soon realized that the ways men are silenced were an inseparable part of my subject, and that each of us exists in a complex of many kinds of silence, including the reciprocal silences we call gender roles. This is a feminist book, yet it is not a book about womens experience alone but about all of oursmen, women, children, and people who are challenging the binaries and boundaries of gender.

This book deals with men who are ardent feminists as well as men who are serial rapists, and it is written in the recognition that all categories are leaky and we must use them provisionally. It addresses the rapid social changes of a revitalized feminist movement in North America and around the world that is not merely altering the laws. Its changing our understanding of consent, power, rights, gender, voice, and representation. It is a gorgeously transformative movement led in particular by the young, on campuses, on social media, in the streets, and my admiration for this fearlessly unapologetic new generation of feminists and human rights activists is vast. As is my fear of the backlash against it, a backlash that is itself evidence of the threat feminism, as part of the broader project of liberation, poses to patriarchy and the status quo.

This book is a tour through carnage, a celebration of liberation and solidarity, insight and empathy, and an investigation of the terms and tools with which we might explore all these things.

The Mother of All Questions

(2015)

I gave a talk on Virginia Woolf a few years ago. During the question period that followed, the subject that seemed to most interest a number of people was whether Woolf should have had children. I answered the question dutifully, noting that Woolf apparently considered having children early in her marriage, after seeing the delight that her sister, Vanessa Bell, took in her own. But over time Woolf came to see reproduction as unwise, perhaps because of her own psychological instability. Or maybe, I suggested, she wanted to be a writer and to give her life over to her art, which she did with extraordinary success. In the talk I had quoted with approval her description of murdering the Angel in the House, the inner voice that tells many women to be self-sacrificing handmaidens to domesticity and the male ego. I was surprised that advocating for throttling the spirit of conventional femininity should lead to this conversation.

What I should have said to that crowd was that our interrogation of Woolfs reproductive status was a soporific and pointless detour from the magnificent questions her work poses. (I think at some point I said, Fuck this shit, which carried the same general message, and moved everyone on from the discussion.) After all, many people make babies; only one made To the Lighthouse and Three Guineas , and we were discussing Woolf because of the latter.

The line of questioning was familiar enough to me. A decade ago, during a conversation that was supposed to be about a book I had written on politics, the British man interviewing me insisted that instead of talking about the products of my mind, we should talk about the fruit of my loins, or the lack thereof. Onstage, he hounded me about why I didnt have children. No answer I gave could satisfy him. His position seemed to be that I must have children, that it was incomprehensible that I did not, and so we had to talk about why I didnt, rather than about the books I did have.

When I got off stage, my Scottish publishers publicistslight, twenty-something, wearing pink ballet slippers and a pretty engagement ring, was scowling in fury. He would never ask a man that, she spat. She was right. (I use that now, framed as a question, to stymie some of the questioners: Would you ask a man that?) Such questions seem to come out of the sense that there are not women , the 51 percent of the human species who are as diverse in their wants and as mysterious in their desires as the other 49 percent, only Woman , who must marry, must breed, must let men in and babies out, like some elevator for the species. At their heart these questions are not questions but assertions that we who fancy ourselves individuals, charting our own courses, are wrong. Brains are individual phenomena producing wildly varying products; uteruses bring forth one kind of creation.

As it happens, there are many reasons why I dont have children: I am very good at birth control; though I love children and adore aunthood, I also love solitude; I was raised by unhappy, unkind people, and I wanted neither to replicate their form of parenting nor to create human beings who might feel about me the way that I sometimes felt about my begetters; the planet is unable to sustain more first-world people, and the future is very uncertain; and I really wanted to write books, which as Ive done it is a fairly consuming vocation. Im not dogmatic about not having kids. I might have had them under other circumstances and been fineas I am now.

Some people want kids but dont have them for various private reasons, medical, emotional, financial, professional; others dont want kids, and thats not anyones business either. Just because the question can be answered doesnt mean that anyone is obliged to answer it, or that it ought to be asked. The interviewers question to me was indecent, because it presumed that women should have children, and that a womans reproductive activities were naturally public business. More fundamentally, the question assumed that there was only one proper way for a woman to live.

But even to say that theres one proper way may be putting the case too optimistically, given that mothers are consistently found wanting, too. A mother may be treated like a criminal for leaving her child alone for five minutes, even if that childs father has left it alone for several years. Some mothers have told me that having children caused them to be treated as bovine nonintellects who should be disregarded. A lot of women I know have been told that they cannot be taken seriously professionally because they will go off and reproduce at some point. And many mothers who do succeed professionally are presumed to be neglecting someone. There is no good answer to how to be a woman; the art may instead lie in how we refuse the question.