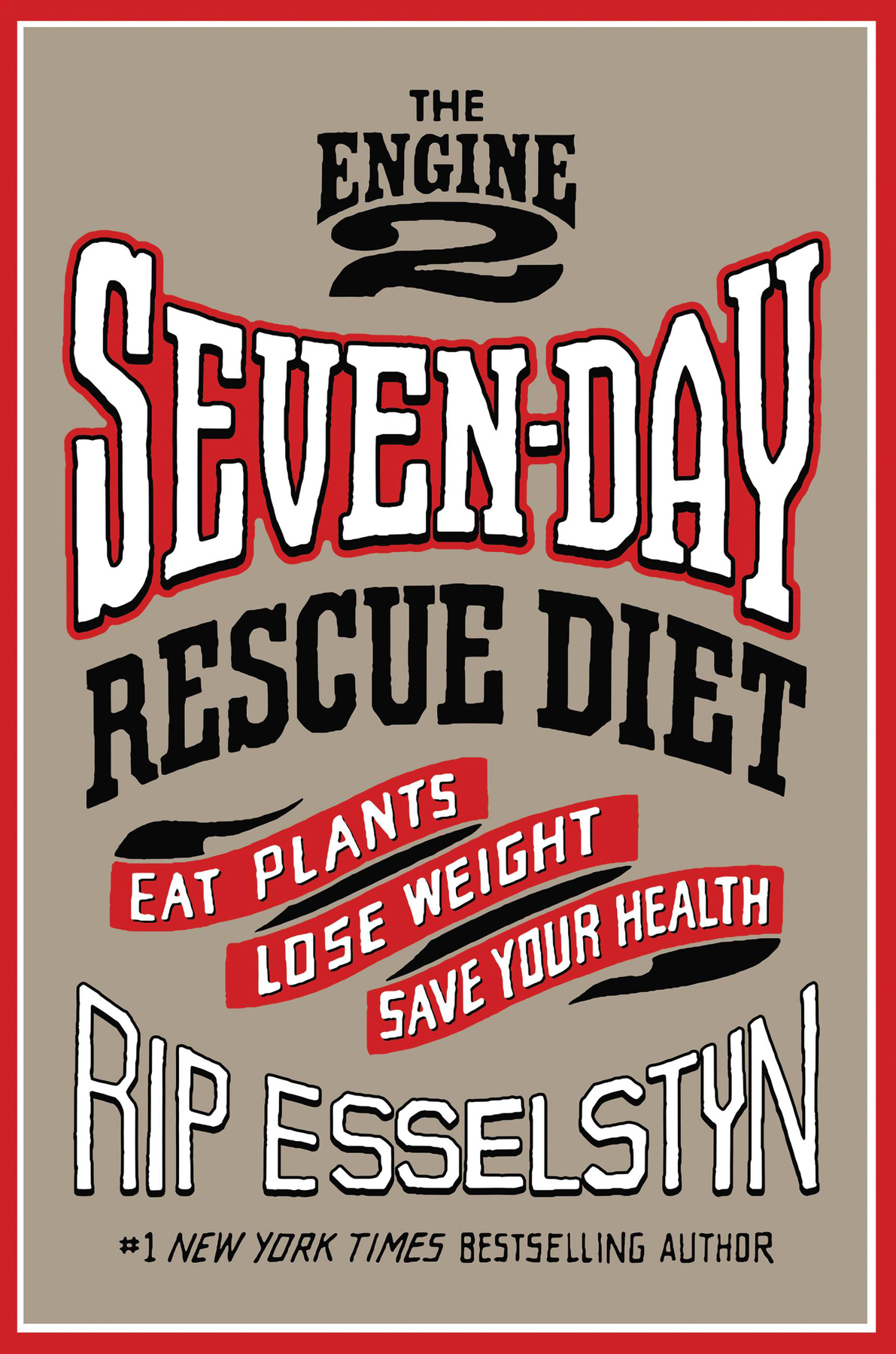

T he week of December 13, 2004, began on a cold and rainy Monday in Austin, Texas. It was the start of some torturous days, but such moments are not uncommon for a firefighter.

Our first call came in to the Engine 2 station at 5:00 a.m.: Lifting assistance. This meant that EMS needed us to help them lift and carry a patient into the ambulance. Unfortunately, this wasnt unusual. This call was like so many others in which we had to help EMS carry people who were morbidly obese. This time, it was a forty-four-year-old woman who weighed 450 pounds and couldnt walk; plus, the hallways in her home were so narrow and abrupt that the stretcher wouldnt fit. We lifted her onto a thick wool blanket, and then we had to maneuver her around tight corners and down the stairway. (Today, instead of blankets, fire departments use a MegaMover, a compact, portable piece of durable material with fourteen handles that can hold up to 1,000 pounds, which was created specifically for the onslaught of lifting-assistance calls that fire and EMS workers respond to.)

It took eight of us to accomplish the task. We positioned two people on each side of the blanket, two people at the front of the blanket, and two people at the rear of the blanket, while one person guided us down the stairs from the front and the eighth person guided us from the rear. Down we went, one step at a time, until we reached the front door, at which point we moved the patient from the blanket onto a hydraulic stretcher and then into the ambulance. (Hydraulic stretchers can handle up to 500 pounds and take a tremendous burden off the backs of emergency service workerswe were throwing out our backs left and right before their existence.)

After we loaded the woman into the ambulance, I asked the EMS workers why she was being transported to the hospital. They told me she had a fever from an infection in her lower leg that wasnt healing and they needed the doctors to look at it. Along with being overweight, the woman had type 2 diabetes. Obesity is actually one of the biggest risk factors for diabetes, which is why the latest term for this one-two punch of obesity with diabetes is diobesity. It is becoming an epidemic in North America.

Back to the station we went. As often happens, we werent there long. We had many other calls involving medical issues that day, including a young man reported as either asleep or unconscious in his car. We slid down the poleyes, Engine 2 is one of only two stations in Austin that still have a real firefighters poleand took off. When we arrived we found the patient shaking uncontrollably, freezing cold, and sweating profusely.

Glancing at his wrist, we noticed a bracelet that indicated he was diabetic. The very first thing we did was check the mans blood sugar. It was a paltry 19 mg/dl (milligrams per deciliter). Anything under 50 mg/dl is considered low. Nineteen mg/dl is dangerously low. When a diabetic patient is unconscious, you cant give him glucose orally, so we waited for EMS to arrive. When they did, they immediately set up an IV and gave the man a shot of glucose. In less than a minute he shot upright and asked, What the hell is going on?

We told him his blood sugar had fallen down to 19. He replied that he couldnt believe it. He had felt tired, decided to take a nap, and that was the last thing he remembered. He said he had been diagnosed as a type 2 diabetic four years previously, at age fifteen. Fifteen! We gave him some solid food to help keep his blood sugar levels elevated for a sustained period and told him to be really careful in the futurethis was a matter of life and death.

Another typical call that week came from one of the University of Texas dorm rooms, where an eighteen-year-old female was suffering from generalized sickness. As is routine, we took her medical history, whereupon she told us that on the advice of her family physician, she was taking 10 mg (milligrams) of Lipitor daily to deal with her high cholesterol levels.