ROUTE 66

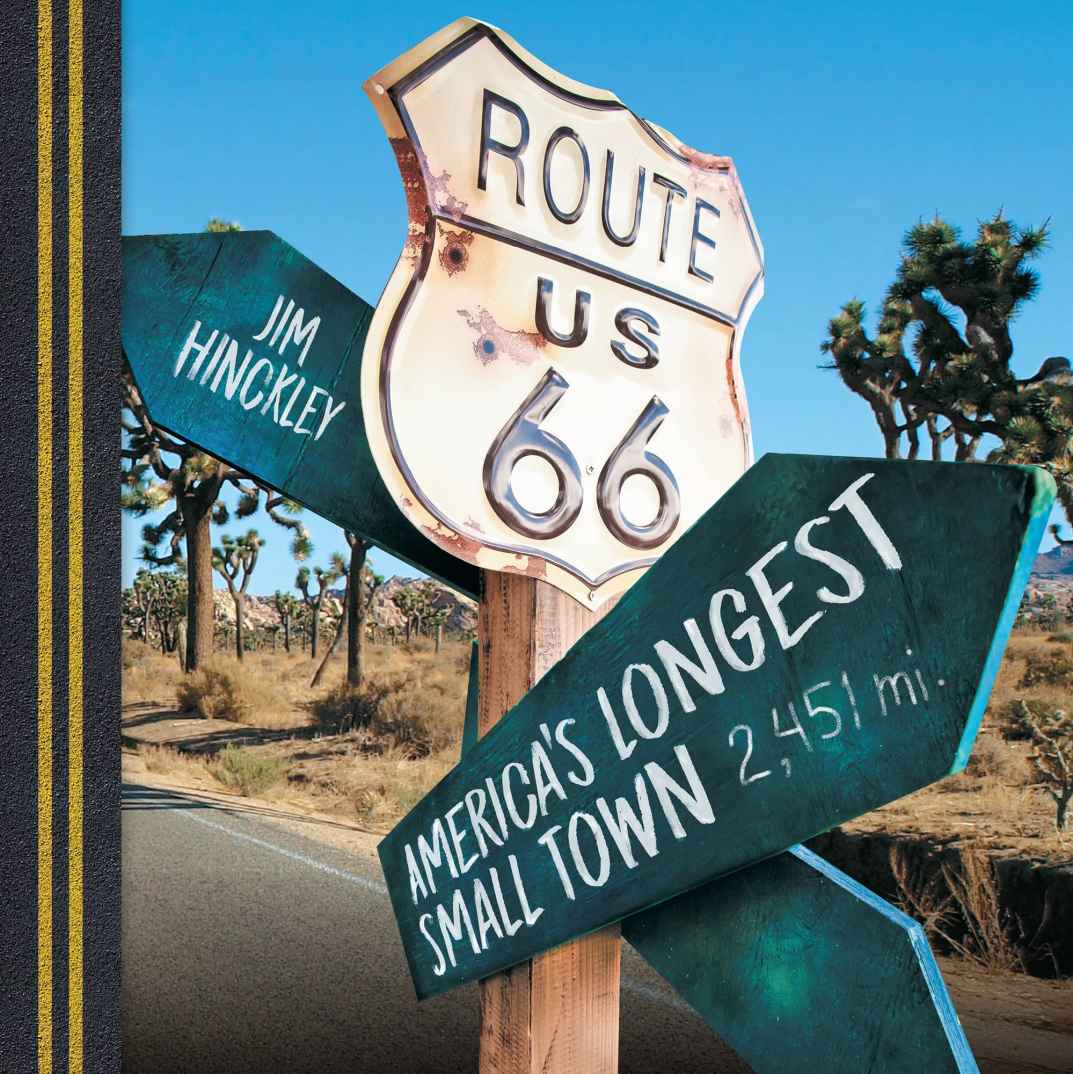

AMERICAS LONGEST SMALL TOWN

TEXT BY

JIM HINCKLEY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

JIM HINCKLEY AND JUDY HINCKLEY

CONTENTS

Guide

INTRODUCTION

Route 66 is firmly rooted in the nations historic roads and trails that were born of our insatiable quest for greener pastures and curiosity about what was over the next hill. The Pontiac Trail and Wire Road, Ozark Trails Highway and Santa Fe Trail, Spanish Trail and National Old Trails Highway, Beale Wagon Road, and Mojave Road are the foundation for what is, arguably, the most famous highway in the world.

However, unlike these roads and trails that became historic footnotes after being rendered obsolete by the nations evolving transportation needs, Route 66 remained relevant. It has also continued to evolve even though, technically, it no longer exists as a US highway.

From that perspective, it is rather fitting that Route 66, in the twenty-first century, has transitioned into a living, breathing time capsule. Though certification of US 66 occurred in 1926, there are tangible links to centuries of American societal evolution along the highways corridor from Chicago to Santa Monica.

It is Americas longest attraction. Museums, festivals, scenic wonders, neon-lit landmarks, and classic tourist traps entice travelers from throughout the world to travel the storied highway where the past, present, and future intersect seamlessly.

In 1927, a marketing campaign branded US 66 as the Main Street of America, a descriptor that is still fitting even though the highway officially ceased to exist in 1984. John Steinbeck referred to it as the Mother Road in The Grapes of Wrath a decade later. Then, in 1946, Bobby Troup penned the highways anthem, and Nat King Cole had most everyone in the country singing a tune about getting your kicks on Route 66.

However, as exciting as the glory days of Route 66 in the 1940s and 1950s were, at least for the segment of American society not restricted by prejudice and segregation, in many ways they seem pale when compared to the era of the highways renaissance. Today, there is a tangible, infectious enthusiasm found all along the route of the old highway and in the international Route 66 community.

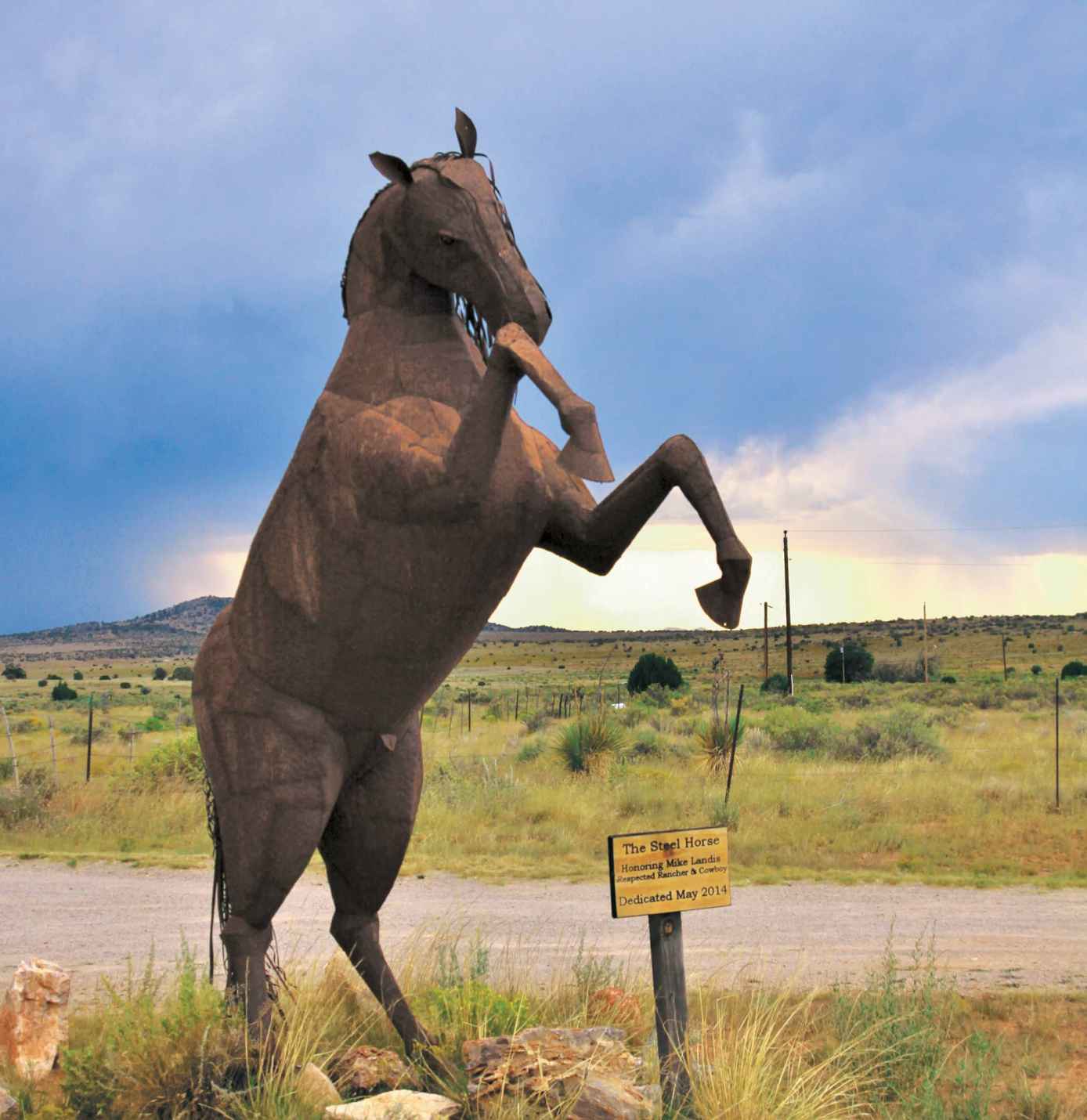

Intertwined along the Route 66 corridor are ghost towns and abandoned truck stops, somber Civil War battlefields and dynamic cities, recently renovated motels and cafs, and businesses that have been under the same management for decades. When driving Route 66 today, you are almost as likely to meet travelers from Australia, Germany, or Japan as you are to meet someone from Alabama, Alaska, or Arizona.

From its inception, Route 66 was a road in a near-constant state of evolution. That trend continues today.

Electric vehicle charging stations share a place with vintage gasoline pumps at renovated historic service stations that now serve as information centers or gift shops. The Route 66 Electric Vehicle Museum, the first of its kind in the world, opened in Kingman, Arizona, in 2014. Formerly abandoned segments of highway with picturesque steel truss bridges are repurposed as bicycle corridors.

However, it is the travelers and business owners, the preservationists and the visionaries who make this highway truly unique and special, and who give it a sense of infectious enthusiasm. With animated tales of adventure, the people who travel Route 66 fuel its ever-growing international popularity, and Route 66 today is a linear community, the nations longest small town.

This book is not merely another guide to iconic Route 66, an almost magical highway. It is a cultural odyssey. As we travel from the shores of Lake Michigan to the Pacific Coast, I will introduce you to some of the people who are at the heart of the highways renaissance, as well as the places that ensure a journey along this highway is a memorable one.

CHAPTER ONE

THE LAND OF LINCOLN

With the advent of the automobile, the nations historic wanderlust was unleashed as never before. The exploits of daring automobilists garnered headlines and sold newspapers, their stories became bestselling books, and the great American road trip was born.

In 1903, Dr. Horatio Jackson of Vermont became the first person to make a transcontinental journey by automobile. Six years later, Norwegian-born A. L. Westgard, a former railroad surveyor, mapped thousands of miles of automobile roads, including the Trail to Sunset that linked Chicago with the Ocean-to-Ocean Highway at Yuma, Arizona.

In 1915, during the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, more than twenty thousand people attended the event from outside the state of California. More than half of these traveled by automobile, including twenty-one-year-old Edsel Ford who also visited natural wonders such as the Grand Canyon on his western adventure along the National Old Trails Highway, predecessor to Route 66.

In the previous year, legendary racers Barney Oldfield, Louis Chevrolet, and other drivers followed the course for the last of the Desert Classic automobile races, derisively labeled as the Cactus Derby, along the National Old Trails Highway (Route 66 after 1926) from Los Angeles to Ash Fork in Arizona. Two years later, Emily Post chronicled her coast-to-coast adventure in a bestselling book, By Motor to the Golden Gate .

In Chicago, the path of Route 66 is through a manmade canyon that represents more than a century of urban architectural evolution. Rhys Martin, Cloudless Lens Photography

In 1915, Edsel Ford, then twenty-one years old, joined thousands of Americans on a grand adventure along the National Old Trails Highway. In 2015, the Historic Vehicle Association re-created his journey.

The seeds for the good roads movement sown in the national bicycle mania of the late nineteenth century and the establishment of the Wheelmen blossomed into a national obsession by the dawning of the new century. In 1902, nine auto clubs in the Chicago area joined to form the American Automobile Association, the AAA.

In 1912, a Daughters of the American Revolution initiative to knit a series of historic roads and trails into a coast-to-coast highway became manifest as the National Old Trails Highway, which followed portions of the Trail to Sunset. Fourteen years later, US 66 followed Westgards pioneering road west through the heart of Chicago. These initiatives were the cornerstone for the US highway system.