The discussion of what is beautiful and what is not has occupied the attention of philosophers, mathematicians, artists, architects, anatomists, surgeons, and theologians for the last 2,500 years. In general terms the idea of beauty applies to the human figure, to animals, and other elements of nature as well as to architecture, design, and artistic representations.

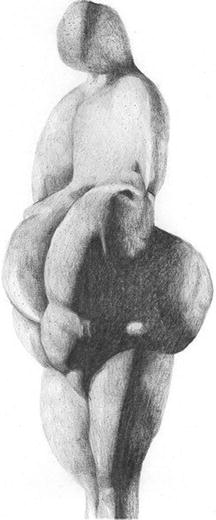

Human representations left by early societies emphasize anatomical features related to fertility, like the wide hips of the Venus de Lespugue and other examples of primitive art associated with obesity suggesting good reserves of fat necessary for survival in times of famine. These desirable qualities were obviously considered beautiful and precede the ideas of Greek philosophers who associated both concepts: beauty and virtue (Fig. ).

Fig. 1

Venus de Lespugue. Prehistoric. Wide hips and abundant body fat emphasize fertility and nutritional reserves

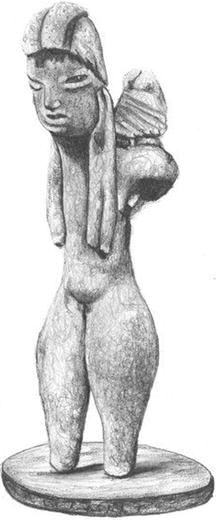

The representation of feminine figures with wide hips associated with fertility is present in many cultures as can be seen in the Cycladic art of 2000 BC and in the deliciously erotic figures from the preclassic period of Mexico, molded around 500 BC not only representing fertility but also an aesthetic ideal (Fig. ).

Fig. 2

Ceramic figure from Tlatilco, Mexico. Preclassic period. Wide hips suggesting fertility. Also notice antimongoloid slanting of the eyes

The Greeks had a passion for beauty and explored the rules for the harmonious proportions applicable to all the things in nature and in art. The search for a mathematical formula for beauty was initiated by Pythagoras, who did not write much but influenced his disciples, including Plato. He developed the theory of harmony and conceived the essence of beauty as the order, proportion, and harmony of the subject. He also considered beauty as a quantitative, mathematical quality that could be expressed in numbers.

Similar ideas were proposed by Philolao in the fifth century BC and further developed by Vitruvio in his book De Architectura written in the first century AD with detailed discussions on the proportions of the human body [].

The return to platonic thinking in relation to beauty appears in the works of Bonaventura de Bagnoregio (Itinerarium mentis in Deum, XII AC) [].

Greek anatomical knowledge based on keen observation of the human body (combined with their passion for beauty) resulted in a magnificent production of sculpture considered to this day as the aesthetic golden standard. These classical proportions were accepted by the Romans who reproduced many of the Greek works preserving the canon of beauty later adopted by the anatomists of the sixteenth century such as Vesalius, Eustachio, Casserius, Mascagni, and many others who followed the Greek models for the illustration of their work [).

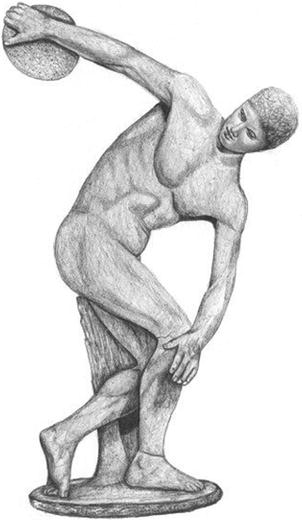

Fig. 3

Discobolo by Myron. V Century BC

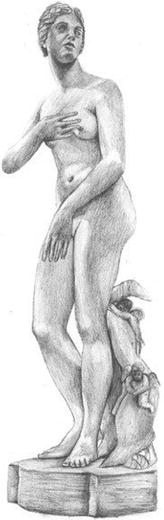

In his work Anatomy for Artists published in 1723, Genga [).

Fig. 4

Aphrodite. A copy of the Greek model by Genga. XVIII Century

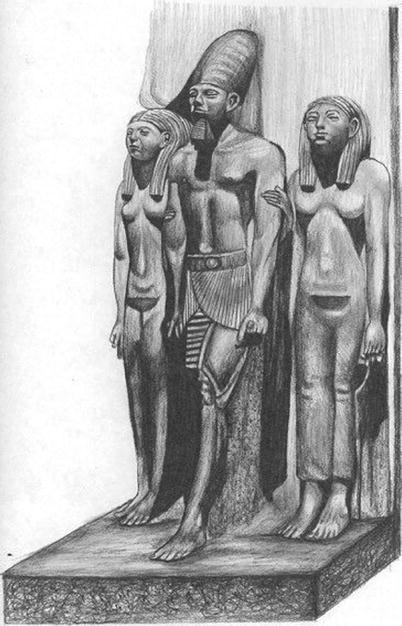

Fig. 5

Egyptian sculpture showing a ruler and his consort with athletic bodies 1500 BC

Many authors during the Renascence maintained the concept of the mathematical formula for beauty. The writings of Piero della Francesca, Fra Luca Paccioli, and especially of Drer contributed to establish an aesthetic canon that had great influence on the work of many artists like Donatello, della Robbia, Verochio, Leonardo, Raphaello, and Michelangelo.

To the south side of the Mediterranean, the Egyptians, before the Greeks, produced marvelous sculptures representing the human body according to the ideal standards of their culture. In all of them a slim athletic figure is emphasized for the Pharaohs and their consorts (Fig. ].

Drer in 1532, following the platonic tradition, published his work on the mathematical expression of the ideal human body. His book was translated from the original German version into Latin by Joaquim Camerarios the Elder in 1557 and later into many languages [).

Fig. 6

Drawing by Albert Drer of ideal female body. XVI Century

Drer, a contemporary of Bellini and Andrea Mantegna, is possibly the most important theoretician in the history of art sharing this honor with Leonardo. His numerous drawings attest also his quality as an artist. His paintings are magnificent representations of the aesthetic concept of the Renaissance. In Adam and Eve he depicted his ideal of beauty with lean athletic figures (Fig. ).

Fig. 7

Adam and Eve by Drer. XVI Century

Durers meticulous measurements of the different parts of the human body established a canon widely adopted by his contemporaries that is still valid today.

This same lean feminine figure was frequently painted by the most distinguished artists. Examples of that are the Venus of Lucas Cranach and the Venus in front of a mirror by Velzquez from the beginning and the middle of the seventeenth century, respectively. Simultaneously other extraordinary artists living in more northern latitudes such as Rubens painted overweight females like the Three Graces. These works did not pretended to be portraits of a specific person so we can assume that his choice of models corresponded to his concept of beauty. Without underestimating the artistic and technical quality of this canvas, the females painted by Rubens would be candidates for dieting and extensive liposuction in the twenty-first century (Figs. ).

Fig. 8

Venus by Lucas Cranach idealizing a lean feminine body. 1506