Lindisfarne Books

610 Main Street, Gt. Barrington, MA 01230

www.lindisfarne.com

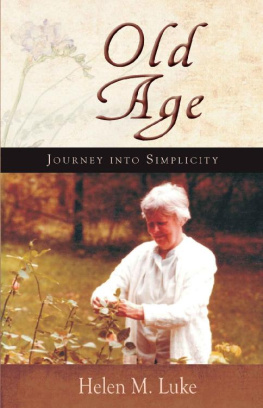

Copyright 2010, Apple Farm Community

Originally published by Parabola Books,

Copyright 1987, Helen M. Luke

The Odyssey, The Tempest, and Little Gidding were originally published as a pamphlet by Apple Farm Community, 1985.

King Lear was originally published in The Inner Story,

Crossroads, copyright 1982, Helen M. Luke.

Suffering originally appeared in PARABOLA,

VIII: 1, January, 1983.

Book design by Gloria Claudia Ortz

Woodcuts by Sally Elliott

ISBN: 978-1-58420-079-6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

T his edition of Helen Luke's Old Age owes its new life to a number of people who deserve recognition for their devotion to Helen and her works. Helen's writings themselves grew out of gatherings in which she discussed her insights with members of the Apple Farm Community and so, of course, a unique and mighty debt of gratitude goes to those who participated in those groups, settled near Apple Farm Community and who continue to contribute in many ways to furthering her legacy.

Special thanks go to Joe Kulin, formerly publisher of Parabola, who offered Helen's writings to a new public through the magazine and Parabola's book and audio divisions.

We at Apple Farm Community are deeply grateful for Joe's abiding interest in and devotion to Helen's works and, especially, for his efforts in getting this book to a new publisher.

Another in that original Parabola family is Lorraine Kisly who first discovered Helen's writings and remains a dear friend of Apple Farm Community.

We also want to thank various particularly generous supporters of Apple Farm who have given generously to see that her works continue to reach new readers; these include Molly Vass and Rob Lehman, John Howie, Barbra Goering, Don Troyer, Joan Miller and Thomas Theis especially.

Apple Farm Community Board of Directors

FOREWORD

A s I write these words I am two months away from my sixtieth birthday. As the decades pile up, new thoughts arrive spontaneously. I think about the age people are as they die around me. Bodily pains and failures have more of the weight of mortality about them, and I wonder what form death will take. I'm aware that my daughter is only eight years old and will probably live most of her life without me. My wife is considerably younger than I, and I think about her going on after me. Of course, God's plan is always full of surprises, but these fantasies are significant in themselves, no matter what happens. They are the soul expressing itself on this day, not just literally about the future but about its situation at the moment.

What I treasure about Helen Luke's remarkable book on old age is that she avoids getting caught up in all the usual worries and sentimentalities. She sees age as a mystery and quite rightly hangs all her thoughts about it on images from literature. And not just literature, but some of the most profound of all imaginative writings, which just happen to be personal favorites of mine.

Her models of aging are eccentrics and foolsholy fools, of course: Odysseus, Lear, and Prospero. I take it that the best way to move into old age is to allow the fool to come forward, to become more and not less an individual following mad attractions. But to perceive and allow the fool, it is necessary to see through the obvious and the literal and grasp the mysterious that plays out in the less ambitious, less focused control of life. The beauty of this book is that it isn't so much about aging as about the soul's process, its ongoing alchemy, responding to changes in the body, in life, and in one's sense of self.

For me the core of this book about the enchantment of age is the theme of Prospero giving up his magic book and his guiding angel and his staff. It looks as though Helen Luke had given up her own magic book when she wrote this one. It is free of instruction, ambition, and the pose of wisdom. I will never forget two statements from other authors she cites: Laurens van der Posttotal surrender to the truth of himself and Charles Williams-I'll break all imposition of views. She is talking about the art of release, the surrender of self, and the paradoxical discovery of what has always been present but never fully embraced.

She writes about forgiveness and prayer, two items we think we know something about, until they become translucent in old age and play central roles in the embrace of one's life and one's world. And the place of mercy in this process. She sees the merc-of mercy in the words merchant and commercially, and points out the importance of exchange and courtesy in old age. But she doesn't mention the merein Mercury, yet Mercury, the imagination at its most free and playful, runs through her entire book as she makes one giant play on aging. The capacity to see through, to see deeply enough, to see what is not obviously presentthese are the gifts of this wonderful little Mercurial book.

I confess I might have expected Helen Luke to be more Jungian here, more explanatory, more psychologically clever. She isn't any of these things. Every sentence flows from many hours of reflection and an openness to experience. She does what a good artist does: she dreams the dream onward, not leaving the realm of mystery for the crisper air of understanding. She offers a gentle push toward an imagination of age, but she doesn't offer a program or a theory. As I say, she practices what she preaches, giving up her own angels and, it appears, her precious ideas.

The reader is invited to do likewise, and you don't have to wait for old age to do it. As Helen Luke intimates, aging is a matter of imagination. You may be disappointed not to find another plan for aging gracefully. If so, give up the expectation. Give up the need for a theory. Break the staff of your need. Drown the book that has become your life manual and proceed to forgiveness and mercy. Read this book and pray.

Thomas Moore

INTRODUCTION

I n the essays that make up this reflection on old age, Helen M. Luke, who has written so perceptively about myth and symbol in life and in art, presents us with perhaps her greatest gift yet: her very potent insights into a phase of life that until now has not been fully incorporated into our understanding of the inner journey. Many men and women today are aware of the tasks of the second half of life, aware that (as Helen Luke expresses it) having eaten the apple and chosen to know good and evil, we have left the infantile Paradise to go individually on the long journey in the dimension of time in which each [learns] through the bitter conflicts of the opposites to discriminate every smallest thing or image as unique and separate. We have glimpsed as our goal that objective cognition which Jung called the central secret, have begun to distinguish the ego from the Self which is ours and not ours. But that is not the end of the journey. A further, crucial step remainsand it is that step, that transition into the last phase of our journey toward death, that Helen Luke addresses in this book on old age.

Drawing on the masterworks of Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, and T.S. Eliot; reading those works with an understanding formed through years of absorbing and reflecting upon the insights of Carl Jung; and speaking as a wonderfully conscious individual making the transition herself into old age, Helen Luke teaches us that a point comes in our lives at which we choose how we go into our last years, how we approach our death. The choice, as she describes it, may be painful, requiring (should we choose to continue to grow old, instead of merely sinking into the aging process) that we let go of much that has been central to us, even to our inner lives. The choice, she says at one point, is whether [we] will hold on to the old man, to rejection of that emptiness which is the fullness of Mercy.

Next page