Introduction

An understanding of the embryology and anatomy of the thyroid gland is essential for clinical-pathologic correlation, especially for the management of thyroglossal duct cysts, thyroid nodules, and tumors. Endocrinologists, dermatologists, radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons all should be familiar with the structure and function of the thyroid gland as it relates to appropriate diagnosis and management of these conditions.

Anatomy

The mature thyroid gland is an H- or U-shaped endocrine organ located in the base of the neck.

The left and right lobes cover the lower sides of the larynx and upper trachea and are connected by a central isthmus. In certain individuals, thyroid tissue extends superiorly along the midline from the thyroid isthmus. This tissue is known as the pyramidal lobe and represents remnants of the embryonic thyroglossal duct. Despite sharing common nomenclature, the thyroid cartilage and thyroid gland do not anatomically overlap significantly. The naming of these two structures was derived from the Greek root meaning shield-shaped. ).

Figure 1.1.

Anatomy of the thyroid gland. I, isthmus; LL, left thyroid lobe; RL, right thyroid lobe; PL, pyramidal lobe

The thyroid isthmus typically overlaps the third tracheal ring and is firmly attached to it by a pre-tracheal fascia also known as Berry's ligament. This firm attachment causes the thyroid gland to move superiorly in response to tracheal elevation during swallowing. This helps differentiate thyroid masses such as thyroid nodules and thyroglossal duct cysts, which move during swallowing, from lymphadenopathy or branchial clefts cysts, which remain stationary.

The thyroid gland lies deep to the strap muscles of the neck. The carotid sheath is located lateral and deep to the thyroid gland and is separated by distinct facial layers. The left lateral portion of the esophagus borders the deep surface of the left thyroid lobe. The parathyroid glands are typically located along the deep surface of each thyroid lobe. The number and location of the parathyroid glands can be extremely variable; this may prove to be frustrating for surgeons intraoperatively.

The thyroid gland receives a rich arterial blood supply from bilateral superior and inferior thyroid arteries. Per gram of tissue, it has one of the highest blood flows of any organ in the body. The superior thyroid artery is the first branch of the external carotid artery above, while the inferior thyroid artery comes from the thyrocervical trunk below. The inferior thyroid artery also supplies both the inferior and superior parathyroid glands. Some research suggests that the superior thyroid artery may also contribute to the perfusion of the superior parathyroid gland. Although the thyroid gland has two pairs of supplying arteries, venous outflow is accomplished through three pairs of veins, termed the superior, middle, and inferior thyroid veins. The superior and middle thyroid veins carry blood back to the internal jugular vein. The inferior thyroid vein has a nearly vertical course inferiorly, until it reaches the brachiocephalic vein.

Lymphatic vessels arise from both lateral thyroid lobes. They extend inferiorly in the central neck compartment before emptying into the thoracic duct. Pretracheal lymph nodes may also become enlarged with thyroid pathology. A single pretra-cheal node may sometimes be palpated in the mid-line of the neck and is referred to as the Delphian node . This was named for the Oracle of Delphi of ancient Greece because this single node may portend an underlying malignancy.

The thyroid gland is innervated by the autonomic nervous system. The parasympathetic branches arise from the vagus nerves, while the sympathetic fibers descend from the superior, middle, and inferior sympathetic ganglia of the sympathetic trunk. The actual effect of the autonomic nervous system on the gland is poorly understood, although it is theorized that most of the effect is to regulate arterial and venous perfusion. The recurrent laryngeal nerve and external superior laryngeal nerve are paired structures that innervate the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, which allow for phonation and respiration. The recurrent laryngeal nerve lies within the tracheoesophageal groove and may even lie within pretracheal fascia as it courses superiorly into the cricothyroid membrane. The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve may be found near the superior thyroid artery until it innervates the cricothyroid muscle. Both nerves may be damaged during thyroid surgery, leading to temporary or permanent hoarseness. Risk of injury to the laryngeal nerves is estimated at 1% during thyroid surgery.

Minor variations of thyroid anatomy are common, especially as the presence of goiters and nodules can distort the overall structure. Inferior hypertrophy of the gland behind the sternum is called a retrosternal thyroid . When severe, a ret-rosternal thyroid may cause significant tracheal compression and airway compromise

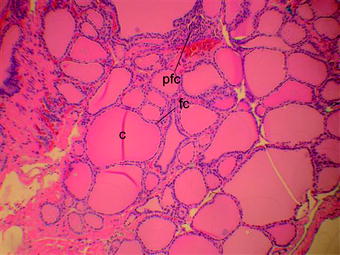

Histologically, the architecture of the thyroid gland is composed of many spherical hollow sacs called thyroid follicles . The follicles are lined by a simple cuboidal epithelium and contain colloid centrally. The colloid lumen stains uniformly pink with hematoxylin and eosin (Figure

Figure 1.2.

Thyroid histology with hematoxylin and eosin staining. C, colloid; fc, follicular cells; pfc, para-follicular cells