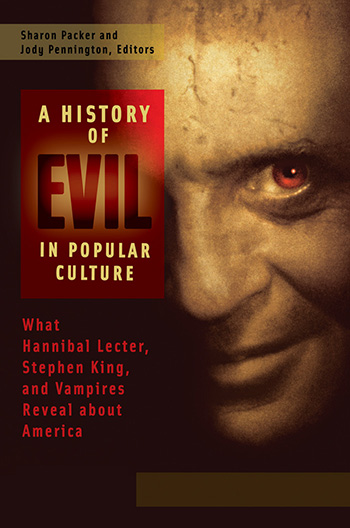

A History of Evil in Popular Culture

A History of Evil in Popular Culture

What Hannibal Lecter, Stephen King, and Vampires Reveal about America

Volume 1: Evil in Film, Television, and Music

Sharon Packer and Jody

Pennington, Editors

Copyright 2014 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A History of Evil in Popular Culture: What Hannibal Lecter, Stephen King, and Vampires Reveal about America / Sharon Packer and Jody Pennington, editors.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-313-39770-7 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-313-39771-4 (ebook)

1. Evil in literature. 2. Evil in motion pictures. 3. EvilSocial aspects.

I. Packer, Sharon, editor of compilation. II. Pennington, Jody W., 1959- editor of compilation.

PN56.E75H57 2014

809'.93353dc23 2014000164

ISBN: 978-0-313-39770-7

EISBN: 978-0-313-39771-4

18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook.

Visit www.abc-clio.com for details.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

| Ted Atkinson |

| Aaron Barlow |

| Tiffany Bergin |

| Jeffrey Bullins |

| Ralph Covino |

| Laura L. Finley and Kelly C. Mannise |

| Justin D. Garca |

| Nicole A. Haggard |

| George Higham |

| Rebecca Housel |

| Brian Ireland |

| Jeff Kerner with Howard Forman |

| William P. Kladky |

| Vincent LoBrutto |

| Yael Maurer |

| Kimberley McMahon-Coleman |

| Cynthia J. Miller |

| Sean Moreland |

| Salvador Jimenez Murguia |

| Robert Peckham |

| Jody Pennington |

| William S. Poole |

| June Pulliam |

| Richard Raskin |

| Eric Sterling |

| Wendy Wright |

| Dale Carter |

| Daniel R. Fredrick |

| Justin D. Garca |

| Katherine L. Turner |

| Ebony A. Utley |

Auschwitz. Treblinka. Dachau. Slave ships of the Middle Passage across the Atlantic. The Killing Fields of Cambodia. The Mai Lai Massacre, Vietnam. Columbine High School. Newton, Connecticut. Century 16 movie theater in a mall in Aurora, Colorado. Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, Oklahoma City. The Twin Towers. Somalia. Bosnia, birthplace of ethnic cleansing. 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, Birmingham. The Rape of Nanking. The Boston Marathon bombing. The City of Sodom. These are places where evil occurred, unequivocally, even though places are not evil per se. Some of these places are American; all of them, or rather the evil that occurred, have had an impact on American society and culture.

Ted Bundy. Richard Speck. Leopold and Loeb. John Wayne Gacy. Jeffrey Dahmer. Charles Manson. Vlad the Impaler. Dr. Mengele. Adolf Hitler. Al Capone. Westley Allen Dodd. Rapists. Wife beaters. School shooters. Child molesters. Evil men, all of them, most Americans would strongly agreeyet there are countries and cultures where child brides are standard fare and where women expect to be beaten by their husbands. Where does evil begin and where does evil end? Is evil a social construction? Is it culturally relative? Can evil vary across jurisdictions? What about cannibals, for example? Are cannibals evil or not? Cannibalism is evil if done by Jeffrey Dahmer or Albert Fish. In 2013, New York Citys cannibal cop was convicted of conspiring to kidnap, cook, kill, and cannibalize women. That was evil. Yet it was not thought to be evil by the Fore on New Guinea, who, until the 1950s, retained the rites of their ancestors and honored their dead by consuming their brains. Beyond the geography of evil, there is the cause of evil: what drives perpetrators? Consider Andrea Yates, the delusional mother of five who drowned her children because she hoped to save their souls from Satans clutches and free hers: was she evil? Or was she psychotic? Does it even matter? News shows and press reports, judges and juries swung back and forth. It is not so clear, not even to the courts that overturned her earlier conviction and eventually found her not guilty by reason of insanity. What about other mothers who watch their sons die for reasons that are not so dissimilar to Yatess reasoning? Does the way we explain causes influence which acts and their perpetrators count as evil?

Hannah, fabled mother of the Maccabee warriors, and one of two heroines of the Chanukah story, watched her seven sons accept death over apostasy. (After their deaths, Hannah committed suicide.) Mary, mother of Jesus, witnessed the sacrifice of her son, supposedly for the salvation of humankind. Other mothers send their sons to war, knowing that the boys may die on the battlefield. The latter examples are deemed honorable, not evil, provided the spectator supports the same value system as the storys protagonist.

Questions about evil continue. As do explanations. Myth, religion, philosophy, sociology, and as in the case of Andrea Yates, psychology, have all weighed in. So too, the works of popular culture and critics interpretations of them.

Tony Soprano, the fictional mobster that hires hit men, aids his psychiatrist when she is raped in a parking garage. Does his single act of kindness override his countless acts of evil? Michael Corleone renounces Satan and all of his works as his henchmen carry out a series of murders. Is he redeemed? What about real-life mobsters who care for their wives, children, and mothers, because they have superegos lacunae that function under certain circumstances but not others? That metapsychological superego lacuna has holes like Swiss cheese, so that it remains intact in some areas and imparts a circumscribed sense of morality, but has glaring gaping holes that relieve the person of remorse for many other acts.

Evil and its cognates in other languagesis the term used to condemn deliberate acts by human beings, acting individually or collectively, that are beyond the moral pale. There is also a category called natural evil, which includes acts of nature, such as typhoons, floods, famine, earthquakes, and even shark attacks. However, some philosophers attribute natural evil to human acts or moral choices. For instance, the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 seemed to be an act of nature, yet commentators of the stature of Jean-Jacques Rousseau linked the death and destruction that followed the earthquake to human choices. By escaping the countryside and moving to coastal cities (which carried the connotation of sin), more people and buildings were in harms way, so suffering escalated after this natural disaster.