Originally, I had thought to complete this work in only one and a half years, but it ended up taking rather longer than planned. I am grateful for all the help and advice I have received during this period. My students at the University of the Ryukyus lent their hands in many tasks, especially in computer assistance, and in building a database for this work. Though I should list the names of each of the many people who helped me, limitations of space mean I cannot do so.

To Mr. Yamazaki Hiroshi of the book selection committee, who gave me the chance to write this historical overview, I wish to express my deep gratitude for his kindness. He waited for more than three years with grace and patience, and I must finish with my thanks to him.

ix

Translators Note and Acknowledgments

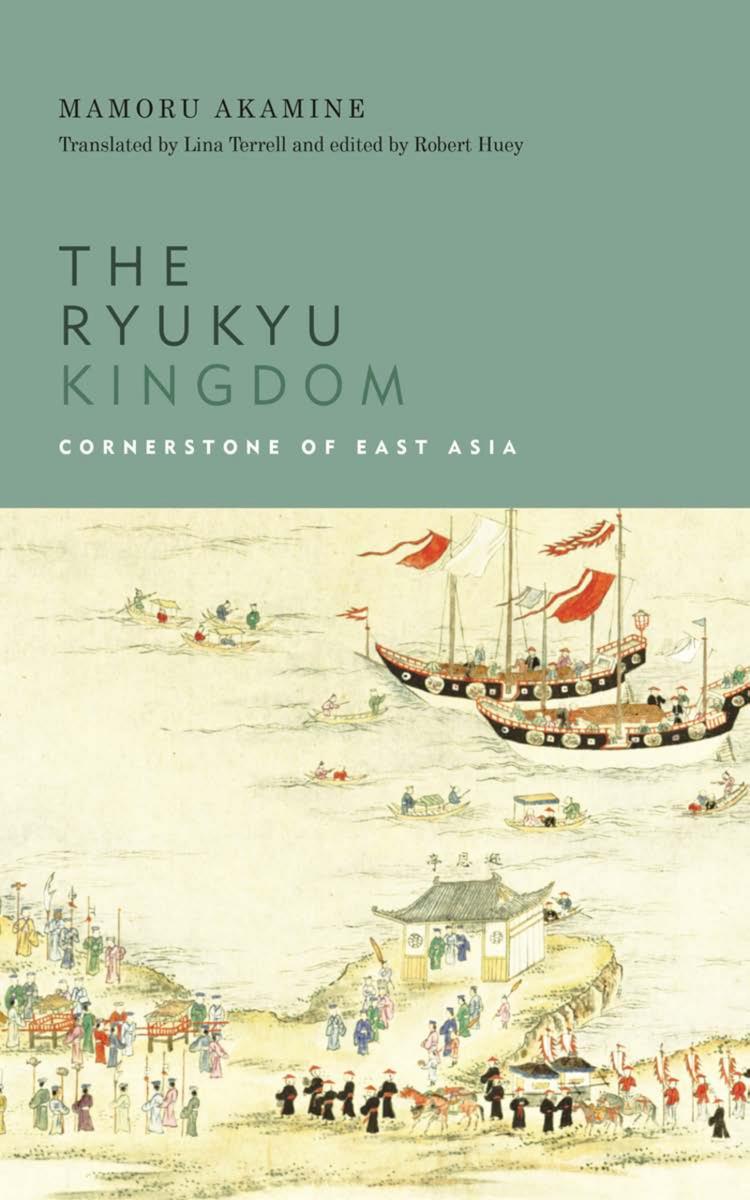

In 2008, to mark the establishment of a Center for Okinawan Studies at the University of Hawaii, scholars of Okinawan studies from the United States, Japan, and Okinawa gathered at East-West Center in a symposium sponsored by the Japan Foundation to discuss the direction that the field of Okinawan studies might take. One of the areas of concern the group identified was the lack of English translations of works by Okinawan writers and scholarsworks that would reflect how those scholars see the issues. This translation is a step toward filling that knowledge gap. Mamoru Akamine was born and raised in Okinawa. After graduating from Meiji University, he received his doctorate from Taiwan National University and is now a professor of history at Ryukyu University. The perspective he bringsevident in the title of the book and its opening and closing sectionsis one that is missing from existing English-language works in the field. He lets Chinese and Korean sources tell much of the story, adding texture and nuance to the Japanese sources that he also marshals.

The bulk of the translation was done by Lina Terrell, supported by a grant from the Japan Foundations Institutional Support Program. Robert Huey subsequently edited and revised the manuscript in consultation with the author. As a result of those consultations, a few minor changes have been made (errors corrected, difficulties clarified, and so on). Further revisions followed from the useful comments of the two outside readers, for whose input we are very grateful.

This book was originally commissioned from the author with a general, nonspecialist audience in mind and was published in 2004 as number 297 in the Kdansha Sensho Mechie series. The author, Mamoru Akamine, wrote x the book as an accessible narrative, using primary and secondary sources in Japanese and Chinese. The external readers of the translation manuscript, however, felt the book had potential as an important scholarly contribution, so following their suggestion, the author added extensive footnotes in 2015 and updated references in the notes and bibliography to include works published since the original the 2004 edition. We have included page numbers in notes where we could. The editor, Robert Huey, transcribed these footnotes and, with the authors consent, also added several footnotes to English-language resources with an eye to aiding future scholars in the field.

By nature, we have the greatest respect for the diversity of languages. The advent of the modern nation-state has created a myth of language homogeneity that certainly did not exist throughout most of the eras covered in this book. (Portuguese apothecary Tom Pires, for example, claimed that more than eighty languages could be heard in sixteenth-century Malacca, where he resided between 1512 and 1515.) We would have liked to demonstrate this by Romanizing names and words in ways that approximated how they actually sounded at the time. However, in order to produce a readable text, we had to make choices regarding Romanization schemes, as well as which languages to feature.

As this book so clearly shows, the Ryukyu Kingdom existed in a complex web of cultures and countries and its representatives needed to be proficient in Chinese, Japanese, or both in order to conduct trade and other negotiations with its neighbors. Also as noted in this book, there were times when individuals in Ryukyu might go by various combinations of names that were Chinese, Japanese, or Ryukyuan. The first issue we faced was how to treat Ryukyuan names and placeswhether to give them a Chinese reading, a Japanese reading, or a Ryukyuan reading. Though our impulse was to do the latter, we decided against it in most cases for several reasons: (1) we would still have to choose whether to use a reading based on modern Okinawan (most likely Shuri dialect), in which case we would have to choose a consistent Romanization system (ee, or , for example; in fact, we have decided to follow the Ryukyu University practice of using a macron, thus ) and impose that reading on all places and names, regardless of whether they were Shuri or not, or (2) we would have to attempt to reconstruct Middle Ryukyuan readings, as well as regional variationssomething well beyond our skill setand come up with a consistent Romanization; and (3) very few bibliographic resources exist that would allow any but specialists to look such words up in other sources. In fact, it was this last issue that helped guide our decision to use Japanese, Romanized in modified Hepburn, as our pillar language when referring to things in or connected to Ryukyu. This would allow interested readers to look more things up on their own, and also recognize xi people and place names from other works on Japan. Furthermore, as an ironic legacy of Japans colonial period, the vast majority of Chinese-language sources cited herein can be accessed in Japanese libraries or archives and are usually searchable there either in kanji or in kana readings.