Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book does not imply endorsement by the author or publisher, nor does mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities imply that they endorse this book, its author, or the publisher.

Internet addresses and telephone numbers given in this book were accurate at the time it went to press.

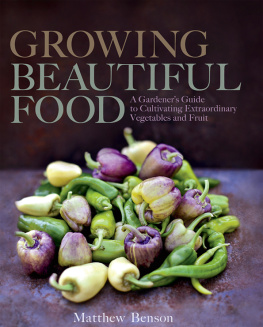

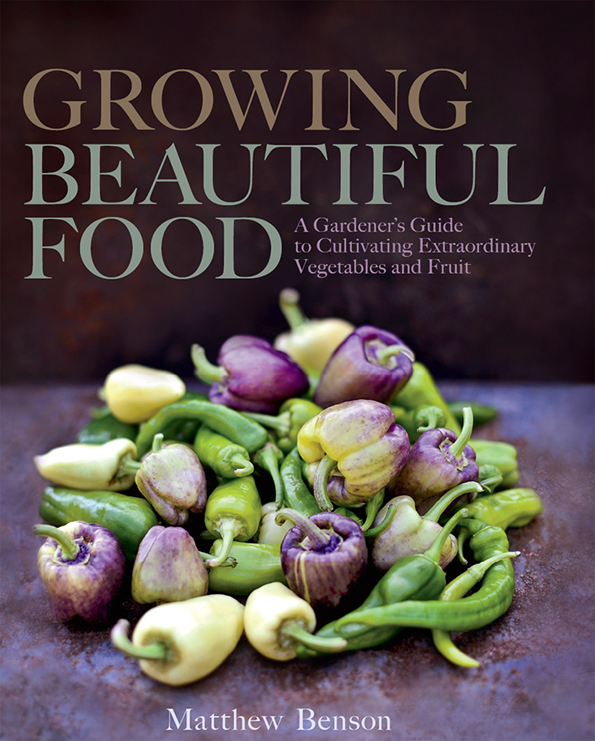

2015 by Matthew Benson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

Rodale books may be purchased for business or promotional use or for special sales.

For information, please write to:

Special Markets Department, Rodale Inc., 733 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Photographs by Matthew Benson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

ISBN 9781623363567 hardcover

eISBN 9781623363574

We inspire and enable people to improve their lives and the world around them.

rodalebooks.com

To all the passionate gardeners and growers of beautiful, organic food

If heaven gave me choice of my position and calling, it should be on a rich spot of earth.... No occupation is so delightful to me as the culture of the earth.... Such a variety of subjects, some one always coming to perfection, the failure of the one repaired by the success of the other.

THOMAS JEFFERSON, IN A LETTER TO CHARLES PEALE, 1811

INTRODUCTION

I ts late spring at Stonegate Farm and Im out in my orchard, ankle deep in henbit and clover, thinning heirloom pear trees of last seasons exuberant growth. The luster of the previous nights rain is still visible in the grass; the air is luminous and warm. Chickens are murmuring in the coop, and a few foraging bees are wandering about, drifting on the slow current of the coming day. Sunlight begins to reach through the fragrant, unfolded bloom of apple, plum, and quince. Twenty years ago, I never could have imagined a morning like this.

I came from citiesphysically, psychologically. From the bump and bustle of urbanism. No planting, no growing, no harvesting. A city park was my closest proxy for cultivated ground. And yet here I am in midlife, an organic farmer, feeding my family, feeding friends, neighbors, strangers; a hardworking steward of a small parcel of agricultural land and unable to imagine any other life.

The idea of farming, like so many of lifes diversions, came to me without much forethought; no tracing the arc of my urban life forward and imagining the weight of organic dirt caked into worn boots, the midnight rustling up of lost and frightened chickens, the fussy coddling of heirloom fruit in an orchard of my own making. Starting a farm for me was an indirect line, a loose scribble in the margins of an established career, but it has helped me to discover something fundamental that was lacking: finding purposeful work thats connected and deeply rooted to place. If, as Jon Kabat-Zinn said in his meditation on everyday life, wherever you go, there you are, then I am here and plan to stay. Planting an orchard or building barns presumes longevity.

So how did I get here? At some point, Id grown weary of cities, of the strange burdens they levy, the false mythology they impose. Life in them had become more like maintenance than real experience. I wanted intimacy with the natural world, to feel connected to forces unknown and perhaps beyond knowing. I wanted a relationship with real, purposeful work, with meaningful sweat. What I didnt know was how to get there. Id never lived off the urban grid, run a hoe across dirt or grubbed at weeds, planted seed, or pruned orchard fruit.

Then I met someone. Someone unique and magical whom I would one day marry. Like me, she had connections with the Old World (her mother was from Munich, and I grew up in Europe), but she was of the earth, not concrete and steel. She had grown up in the gatehouse of a rambling old estate property in the Hudson Valley, outside of Newburgh, New York, in the hamlet of Balmville, and after traveling the world had returned. The home and family she knew had changed. Her only brother had died in a climbing accident, and her mother was battling the last stages of pancreatic cancer, so I came into her life when it was broken by grief, and I was determined to try to make things right for her, and for us.

The healing began with a garden. Set in the stone foundation of an old barn on the property, we cleared back decades of obstinate weeds; built a formal parterre for herbs, vegetables, and flowers; and even patiently espaliered fruit trees against a foundation wall. Friends from the city visited and helped paint fences, fork over garden beds, and move stone. We ambitiously took on other projects on the property, as though they were metaphors for change and renewal, and were soon deeply taken in by the restoration of the place. We were both being restored, of course, by the process: she from the heartbreak of loss, and I from the frazzle and dislocation of urban life. The idea of a future farm, though only a faint glint of an idea at the time, had already begun its provocative dance.

Soon, a few colorful bantam hens arrived to animate the garden, laying their half-size eggs and happily clucking about. They took up roost in the old potting shed (christened La Cage aux Fowl), and my young children named them all. We marveled when eggs as smooth and blue as beach glass were laid, or when our hens would be murmuring softly around the garden table at dinnera meal that wed harvested only 20 feet away. Of course, once youve started to grow your own and had the transformative experience of eating as locally as your backyard, theres really no turning back. Perennials borders will soon be interplanted with tomatoes and eggplant, decorative trees will lose out to those that bear fruit, and fussy rose beds and clematis will make way for compost. This is the beautiful, dangerous progression: where nothing is more local, delicious, and fulfilling than your own edible garden, and more truly is more. Youll run out of space long before you run out of appetite and desire.

My own aspirations to live a more balanced, sustainable life were met the moment I first visited Stonegate. When I first came through the estates massive stone gates, an entranceway that would one day impose itself on the naming of the farm, I was taken in. There was something about this place, the way the buildings stood on the land; so easily clustered, as though in casual conversation. How they played with shadow and light with everything reaching upthe vertical battens, the Gothic finials, the cupolas. Like the perennials in the future garden, or the fruit trees on the farm Id conjured but had yet to make, oreven