For Heidi, Daisy, and Miles

contents

introduction:

The More Beautiful Question

introduction

The More Beautiful Question

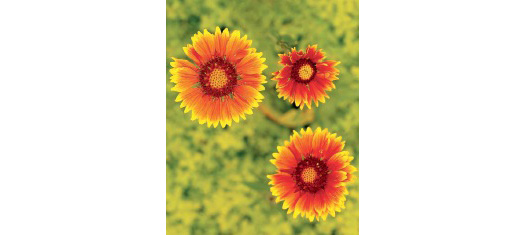

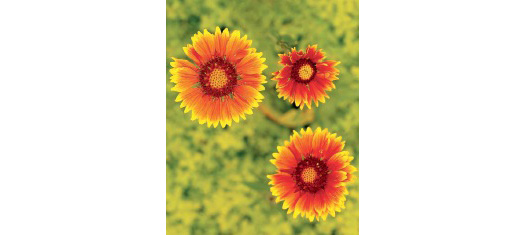

Instinct tells us: See a beautiful garden, a glorious blossom, a splash of perennial colortake out the camera and click. You know that this perfect light, this fragile, miraculous beauty is fleeting. Best to capture it.

But knowing how best to capture it eludes many of us. You put your camera to your eye and shoot away, only to delete the image later when your lowly pixels disappoint: too dark, too light, too much contrast, too little focus, or too awkward of a composition. All the aesthetic excitement you experienced in the garden has perished, and youre left with a pile of forgettable megapixels.

Sound familiar? Anyone who has ever walked through a garden, camera clutched firmly in hand, knows that the rich sensory imprint of color, light, and form can almost overwhelm the senses, yet the photographs we take are often a weak surrogate of the remembered experience.

So how do you rein in your impressions and bring them vividly to life in pictures? How do you create an evocative impression of the place? Perhaps you begin by editing out the distractions and extraneous information, and focus in on what matters to youwhat tells your story of this garden.

The garden experience is always a personal one, and your images should reflect that understanding. While some of us are drawn to the wildflower meadow, to a bit of loose, natural chaos in our otherwise orderly lives, others respond to the strict symmetry of formal gardens, with their linear hierarchies and historical references, creating order and beauty in a chaotic world. Whatever your visual disposition, the camera is an extension not only of your eye, but also of your creative temperament.

The camera is a seeker, after all. Through the camera, we give ourselves the liberty to explore, to wonder, and to render the world through our own intuitive sensibility. But the camera also has a point of view. The world looks different through it; its perspective is edited and directed, focused on a singular idea.

This is no small technological feat when you consider how fully the garden engages all of the senses. Gardens are a source of great intuitive comfort; we know them in our DNA. We know the repetition of form and pattern, the way light moves through leaves and petals and sweeps across a smooth expanse of lawn, and the artful balance of color from one bloom to the next. These are familiar references for those who garden.

But how best to record the fleeting moment? Still photography seems to have its limitations: Theres no movement, no sound, no scentjust two-dimensional stillness. Yet an effective image has the power of invocation; in the best photographs, all of the senses are aroused.

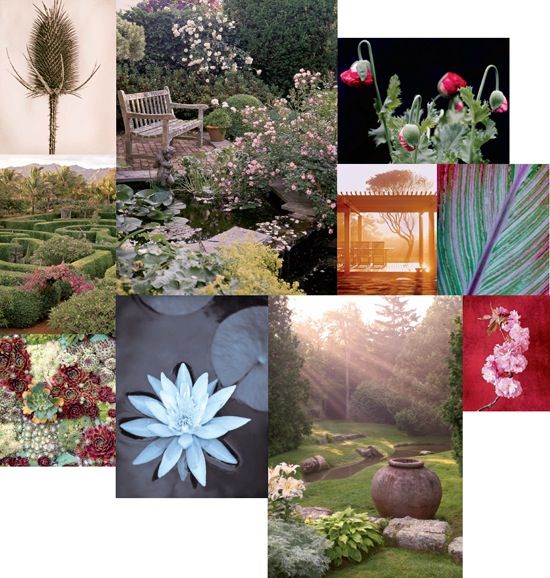

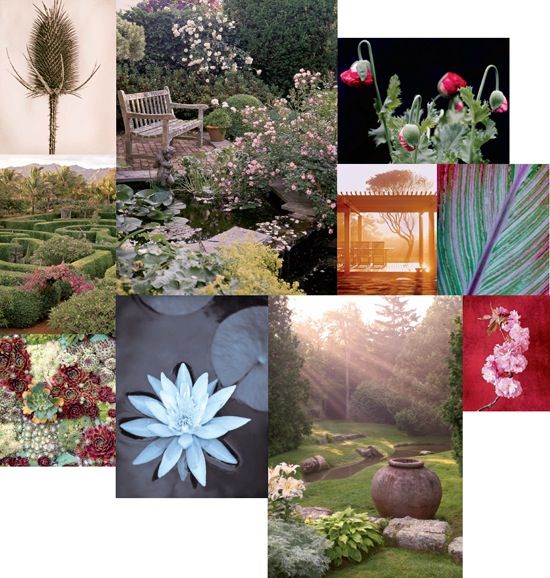

This garden plays beautifully with light, form, and color. Its bones are strong and directional, leading the eye gracefully up, around, and through.

The most successful garden photography is a perfect fusion of technical literacy, narrative intent, and aesthetic understanding. Technology doesnt tell you what visual ideas to have, of course; it is only there to do your bidding, but each photograph has a story to tell and a configuration of light, form, and color that makes it unique.

The Photographic Garden is a garden of visual ideas, captured and skillfully evoked by the camera. This book is meant to make you a better, more intuitive artist in the landscape, to foster a deeper understanding of design and aesthetics, and to encourage the development of your own visual sensibility.

It is not only a photographic exploration of gardens, but also an introduction to digital image-making tools, from cameras to postproduction software. Gigabytes of storage on cameras and computers, as well as remarkable editing programs, have freed up the old constraints of film.

More than ever, we can be open to not knowing, be willing to fail, be able to ask the more beautiful questionto look at the visual world around us and be compelled to wonder: What if I shot it this way, or tried it that way? How could I make this image more beautiful? The consequences of an aesthetic leap of faith will only lead your photography forward.

Though technology may have changed the tools we use to capture and render images, the fundamentals of what makes a compelling photograph or gives a photographer a great eye have not changed. Understanding light and composition has not changed. The infinitely complex and beautiful pattern language of the natural world has not changed; but how you see it is about to.

This book is meant for gardeners who wish to photograph better, and who want to learn to see the garden differently through the camera. Those who garden already have a love affair with plants and planted spaces, with the beauty and complexity of nature, with all the metaphors of what it means to garden and to care for living things. The camera in the garden both informs and deepens our understanding of the natural world and its aesthetic cultivation.

The garden holds a mirror up to us; it speaks to our conceits and frailties, to our desire for purpose and meaning. The Buddhists counsel that if you do one thing with your life, make a garden, and we do. We plant and nurture, we imagine and design, we weed, we prune, and we falter and prevail. There is a rhythm and purpose in the garden that strongly mimics the arc of our own lives. In our efforts to be beautiful, healthy, successful, and happy, the garden is a life partner, a reminder of the extraordinary but impermanent cycle of all things.

Though the camera sees the garden differently than our eyes do, it can teach us much about color and design, about light and form. A garden considered through the camera is very attentive to composed space and to qualities of light. The camera, with its Apollonian desire for order and beauty, reins in wildness and makes it reachable. And just as you would not deliberately design and cultivate a garden absent of beauty, you should be as particular when composing through the lens. Think of the camera as a guide and confidant, there to help you see more fully and deeply. Think of the photographic garden as a sensory expression, taken in largely by the eyes, and refined by the camera.

Learning to see the garden photographically will make you a better garden designer, tuning your eye to the complex textural detail of plants, to the way they hold and transmit light, and to their posture and habit. The camera reveals archetypes of color and composition that the eye can miss, and it speaks in a pattern language all its own. With the camera you are developing your ability to see and heightening your aesthetic sensibility, all of which will make you both a better photographer and a better gardener.

Next page