THE TUDORS

John Guy

New York / London

www.sterlingpublishing.com

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

First published in 1984 as in The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain, the text of this book was revised and expanded in 2000.

Original text Oxford University Press 1984; expanded and revised text John Guy 2000.

Illustrated edition published in 2010 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Additional text 2010 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: The DesignWorks Group

Please see picture credits on page 158 for image copyright information.

Printed in China

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7539-0

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales

Department at 800-805-5489 or .

Frontispiece: This detail from The Family of Henry VIII, a c. 1545 royal portrait by an unknown artist, shows young Prince Edward to the left of the king. To the right is Jane Seymour, his third wife.

CONTENTS

The insignia of the Order of the GarterBritains highest order of chivalryare shown in this detail from an Elizabethan-era map.

ONE

Economic Changes

THE AGE OF THE TUDORS has left its impact on the English-speaking world as a watershed. Hallowed tradition, native patriotism, and post-imperial gloom have united to swell our appreciation of the period as a golden age. Names alone evoke a phoenix-glowHenry VIII, Elizabeth I, and Mary Stuart among the sovereigns of England and Scotland; Wolsey, William Cecil, and Leicester among the politicians; Marlowe, Shakespeare, Hilliard, and Byrd among the creative artists. The splendors of the court of Henry VIII; the fortitude of Sir Thomas More; the making of the English Bible, Prayer Book, and Church of England; the development of Parliament; the defeat of the Armada; the Shakespearian moment; and the legacy of Tudor domestic architecturethese are the undoubted climaxes of a simplified orthodoxy in which genius, romance, and tragedy are superabundant.

Reality is inevitably more complex, less glamorous, and more interesting than myth. The most potent forces within Tudor England were often social, economic, and demographic ones. Thus if the period became a golden age, it was primarily because the considerable growth in population that occurred between 1500 and the death of Elizabeth I did not so dangerously exceed the capacity of available resources, particularly food supplies, as to precipitate a Malthusian crisis. Famine and disease unquestionably disrupted and disturbed the Tudor economy, but they did not raze it to its foundations, as in the fourteenth century. More positively, the increased manpower and demand that sprang from rising population stimulated economic growth and the commercialization of agriculture, encouraged trade and urban renewal, inspired a housing revolution, enhanced the sophistication of manners, especially in London, and (more arguably) bolstered new and exciting attitudes among the English people, notably individualistic ones derived from Reformation ideals and Calvinist theology.

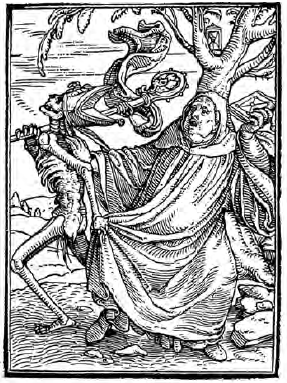

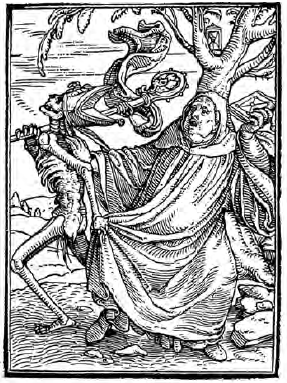

Plague was a near-constant presence in late medieval Europe. This illustration of the danse macabre from a c. 1526 series of woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Youngerpresents a reminder that death will come to all, no matter their station.

Recovery of Population

The matter is debatable, but there is much to be said for the view that England was economically healthier, more expansive, and more optimistic under the Tudors than at any time since the Roman occupation of Britain. Certainly, the contrast with the fifteenth century was dramatic. In the hundred or so years before Henry VII became king of England in 1485, England had been under-populated, underdeveloped, and inward-looking compared with other Western states, notably France. The countrys recovery after the ravages of the Black Death had been slowslower than in France, Germany, Switzerland, and some Italian cities. The process of economic recovery in preindustrial societies was basically one of recovery of population, and figures will be useful. On the eve of the Black Death (1348), the population of England and Wales was between 4 and 5 million; by 1377, successive plagues had reduced it to 2.5 million. Yet the figure for England (without Wales) was still no higher than 2.26 million in 1525, and it is transparently clear that the striking feature of English demographic history between the Black Death and the reign of Henry VIII is the stagnancy of population which persisted until the 1520s. However, the growth of population rapidly accelerated after 1525.

Between 1525 and 1541 the population grew extremely fast, an impressive burst of expansion after long inertia. This rate of growth slackened off somewhat after 1541, but the Tudor population continued to increase steadily and inexorably, with a temporary reversal only in the late 1550s, to reach 4.1 million in 1601. In addition, the population of Wales grew from about 210,000 in 1500 to 380,000 by 1603.

| English Population Totals 15251601 |

| YEAR | POPULATION TOTAL IN MILLIONS |

| 1525 | 2.26 |

| 1541 | 2.77 |

| 1551 | 3.01 |

| 1561 | 2.98 |

| 1581 | 3.60 |

| 1601 | 4.10 |

| Source: E. A. Wrigley and R. S. Schofield, The Population History of England, 15411871, London, 1981) |

Problems of Adjustment

While England reaped the fruits of the recovery of population in the sixteenth century, however, serious problems of adjustment were encountered. The impact of a sudden crescendo in demand, and pressure on available resources of food and clothing, within a society that was still overwhelmingly agrarian was to be as painful as it was, ultimately, beneficial. The morale of countless ordinary English people was to be wrecked by problems that were too massive to be ameliorated either by governments or by traditional, ecclesiastical philanthropy. Inflation, speculation in land, enclosures, unemployment, vagrancy, poverty, and urban squalor were the most pernicious evils of Tudor England, and these were the wider symptoms of population growth and agricultural commercialization. In the fifteenth century farm rents had been discounted, because tenants were so elusive; lords had abandoned direct exploitation of their demesnes, which were leased to tenants on favorable terms. Rents had been low, too, on peasants customary holdings; labor services had been commuted, and servile villeinage had virtually disappeared by 1485. At the same time, money wages had risen to reflect the contraction of the wage-labor force after 1348, and food prices had fallen in reply to reduced market demand. But rising demand after 1500 burst the bubble of artificial prosperity born of stagnant population. Land hunger led to soaring rents. Tenants of farms and copyholders were evicted by business-minded landlords. Several adjacent farms would be conjoined, and amalgamated for profit, by outside investors at the expense of sitting tenants. Marginal land would be converted to pasture for more profitable sheep-rearing. Commons were enclosed, and waste land reclaimed, by landlords or squatters, with consequent extinction of common grazing rights. The literary opinion that the active Tudor land market nurtured a new entrepreneurial class of greedy capitalists grinding the faces of the poor is an exaggeration. Yet it is fair to say that not all landowners, claimants, and squatters were scrupulous in their attitudes; a vigorous market arose among dealers in defective titles to land, with resulting harassment of many legitimate occupiers.

Next page