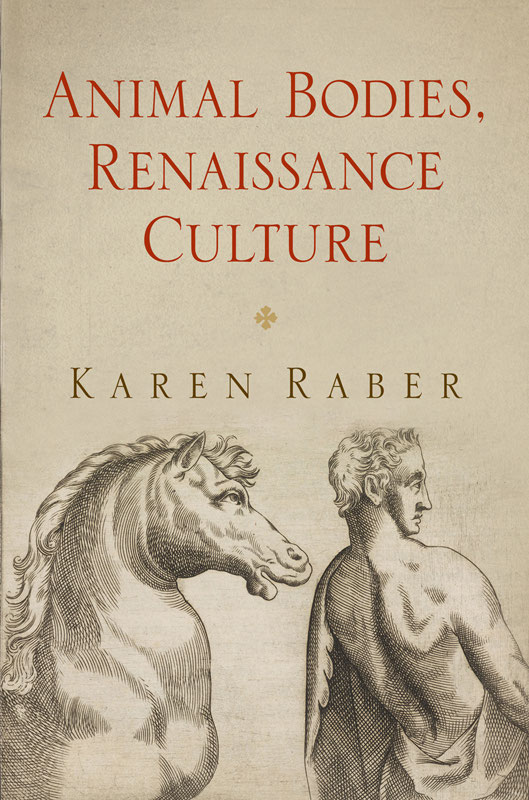

Karen Raber - Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture

Here you can read online Karen Raber - Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pennsylvania Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture

HANEY FOUNDATION SERIES

A volume in the Haney Foundation Series,

established in 1961 with the generous support

of Dr. John Louis Haney

Animal Bodies,

Renaissance Culture

KAREN RABER

Copyright 2013 university of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for

purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book

may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Raber, Karen, 1961

Animal bodies, Renaissance culture / Karen Raber.

1st ed.

p. cm. (Haney Foundation series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4536-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Animals (Philosophy)EuropeHistory16th

century. 2. Animals (Philosophy)EuropeHistory

17th century. 3. Animal intelligencePhilosophy

History16th century. 4. Animal intelligence

PhilosophyHistory17th century. 5. Human-animal

relationshipsEuropeHistory16th century.

6. Human-animal relationshipsEuropeHistory

17th century. 7. Human beingsAnimal nature

History16th century. 8. Human beingsAnimal

natureHistory17th century. I. Title. II. Series: Haney

Foundation series.

B105.A55R33 2013

113.8dc23

2013004238

Giovanni Battista Gellis Circe of 1549 recounts Ulysses efforts to convince a variety of beasts, transformed from men by Circe, that they should return to their human form and leave her island with him. Ulysses begins with the humblest of creatures, the oyster and the mole (also the simplest and humblest of humans, a fisherman and a ploughman respectively), but upon being soundly rejected, decides to move on to other creatures more likely to understand his appeal to reason: Thou shalt find some [men] of such knowledge and wit, he remarks to Circe, that they are almost lyke unto the goddes, and some others of so grosse wytte, and small knowledge, that they seme almost bestes. Assuming he has met only men who were dull witted in their human forms, or whiles they were men, never knew themselves, nor never knewe their own nature, but they attended onely to the bodye, Ulysses keeps trying new tacks with new interlocutors. Moving through his own version of a great chain of being to a snake, a hare, a lion, a horse, a goat, a hind, a dog, a calf, and an elephant, Ulysses proposes different arguments in support of human superiority. But in each debate, the famous orators persuasion returns again and again to the idea that reason is the basis of human excellence; so he tells the lion that animals cannot claim true virtues because amongst beastes there is no fortitude at all, but onle amonge menne, since fortitude is a meane, determined with reasonne, betwene boldenes and feare because you have not the discourse of reason, whereby you might eyther knowe the good or the honest, and by occasion thereof, onely you put your selves in daungers; but you do it eyther for profyte or for pleasure, or to revenge some injurie. And this is not fortitude (sig. l4r). Again, he tells the horse, temperance is an elective habit, made with a right discourse of reason; howe can you then have this virtue in you? (sig. n4r). However, each and every animal rejects Ulysses proposed gift of humanity, arguing that its beastly condition is superior. Not until he debates with the elephant, once a human philosopher, does he find someone who shares his philosophical language, and whom he is able to convince that humans are the most noble, the most virtuous creatures because they are rational, and are not limited by the sensory memory, experience, and instinct that is all animals possess. Transformed, the elephant, now restored to human identity as Aglafemos, cries out, Oh what a marveylous thing it is to be a man! (sig. t2r).

Of course, having found his convert, Ulysses must then warn him that there are some things that even human beings cannot know, such as the first cause of life, because they are hampered by their bodies and the shortness of their lives. Although he has categorically rejected the claims of all his targets to a better life in animal form by privileging reason and discounting the body, it turns out that the body is a limiting factor even for humans. Indeed, this conclusion of the Circe sends us back to reevaluate the positions of even the very simplest of the animals, each of whom makes a strong case that human bodies are, in fact, far inferior to beastly ones. The oyster, for instance, argues that unlike humans animals do not have to labor to create their food and clothing, and goes on: I have reason, consideringe besides this that nature hath set so litle store by you, for besides the bringing forth of you naked, she also hath not made you any hose or habitation of your own, wher[e] you mought defend you from thinjuries of the wether, as she has made to us, which is a plaine toke that you are as rebelles and banished of this world, having no place here of your owne (sig. B4r). Likewise, the mole answers the charge that his condition is defined by lack, particularly of sight, by pointing out that humans come into the world weeping because they are embarking on a life of misery and suffering. And why for syns it [seeing] is not necessarye to my nature, it is sufficient to me, to be perfit in myne owne kynde, concludes the mole, and reiterates, for that I am perfecte in thys my kynd (sig. c3r). Even the oyster and the mole, the lowest of low creatures, see themselves as physically and therefore morally perfect in contrast to humans, and assert that it would defy reasontheir perfect reason, which accepts their god-given condition in lifefor them to return to their human forms.

Gellis dialogue derives its premise from Plutarchs Whether the Beasts Have the Use of Reason, also titled Gryllus, in the Moralia. Where Plutarch offers only one recalcitrant pig, however, Gelli explores additional dimensions of animal and human reason and embodiment, as well as issues of class and economic privilege, through his additional animal characters. Gellis text was popular, enjoying numerous reprints by the end of the century. Its first English translator, Henry Iden, justifies his efforts by recommending the dialogue for those who know no other language than their owne, to see herein how lyke the brute beast, and farre from his perfection man is, without the understanding and folowinge of dyvyne thynges (sig. a2r). And indeed, Ulysses ostensibly rational positions are again and again ignored, inverted, or countered with narrow examples of animal contentment. However, the conversion of Aglafemos hardly counterbalances the influence of the other animals often compelling positions, nor does it fully vindicate the self-blind and blithely self-congratulatory Ulysses. Where the text underscores human frailty, the tone shifts to pathos, suggesting (perhaps despite its apparent goals) that human reason is small compensation for the evils of existence in a weaker human body, subject to social, political, and economic forces that make life harder, not more rewarding. In this, Gelli expands on elements of Plutarchs original dialogue, in which Gryllus does a pretty good job of defending animal intelligence and impugning human virtues.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture»

Look at similar books to Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.