Table of Contents

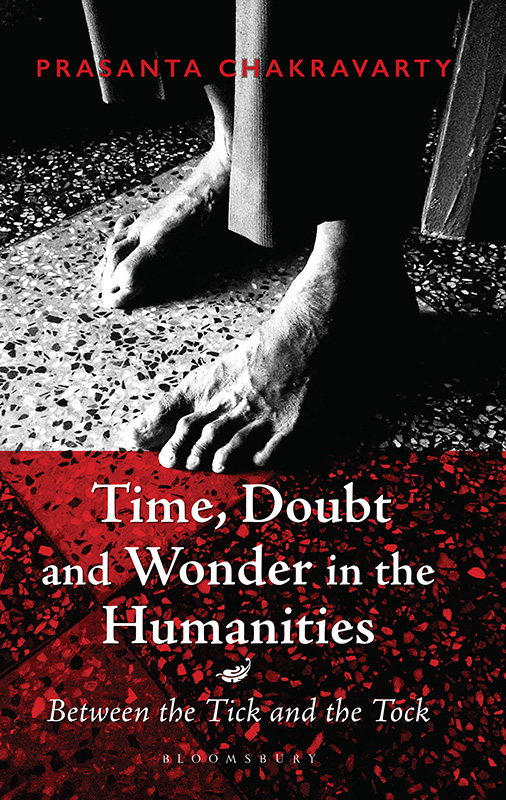

Time, Doubt and Wonder in the Humanities

Time, Doubt and

Wonder in the Humanities

Between the Tick and the Tock

Prasanta Chakravarty

BLOOMSBURY INDIA

Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

Second Floor, LSC Building No. 4, DDA Complex, Pocket C 6 & 7,

Vasant Kunj New Delhi 110070

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC INDIA and the Diana logo are trademarks of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in India 2019

This edition published 2019

Copyright Prasanta Chakravarty, 2019

Prasanta Chakravarty has asserted his right under the Indian Copyright Act to be identified as the Author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

ISBN: HB: 978-9-3881-3424-8; eBook: 978-9-3881-3426-2

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Created by Manipal Digital Systems

Printed and bound in India by Thomson Press Pvt Ltd

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc makes every effort to ensure that the papers used in the manufacture of our books are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. Our manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

Dazzling, erudite, simultaneously charming and assaulting, this analysis of affects, disturbing and strange affects, and especially wonder, the most elusive of affects and the most energising of moods, shines a new light on the forces of time and becoming. At once a deeply political analysis of the present and a meditation of its impossibility, these extraordinary essays open out our understanding of what the humanities, and especially the arts, can do in times of crisis.

Elizabeth Grosz, Jean Fox OBarr Womens Studies Professor, Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, Duke University

Anyone demoralised about the situation of humanities in an anti-intellectual and greed-driven era will be heartened by this path-breaking and searching study. Prasanta Chakravarty has gathered here essays on topics that range from the importance of Luther to the Torah as literature toeighteenth-century minstrelsy. His meditations on such historical topics are interwoven with readings of important Bengali and Hindi poets of several generations, new insights into the poems of Basil Bunting and David Jones, and thoughts on the quality of academic life within the University of Delhi, where he teaches. Underlying all of his work is a concern with the common human experiences of time and the senses, and the ways our belief systems, so often mutually unintelligible, which nevertheless speak to a shared desire to live beyond the merely literal.

Susan Stewart, Poet and Avalon Foundation University Professor of Humanities, Princeton University

Prasanta Chakravartys book is a furious, irresistible ride between philosophy, literature and politics. It displays an amazing erudition and mobilises dozens of ideas and authors, from classics to contemporary critical thought, passing through German, English and Hindi poetry. Advancing through this labyrinth of concepts and images with elegance and astuteness, Chakravarty explores the enigma of time. Between Chronos and Kairos, his praxical imagination fruitfully discloses new horizons of hope.

Enzo Traverso, Susan and Barton Winokur Professor in the Humanities, Cornell University

All enemies, who provide density to living

Contents

The German poet, playwright and novelist Heinrich Von Kleist tells us of the marionette puppet theatre that the graceful and rhythmic dance movements of its mute figurines entirely depend on the centre of gravity in each puppet. The puppeteer lets the mechanics follow its own rhythm: When the centre of gravity is moved in a straight line, the limbs describe curves. Often shaken in a purely haphazard way, the puppet falls into a kind of rhythmic movement which resembles dance (Kleist, 2004). The job can be done entirely without sensitivity or without much idea on the part of the puppeteer about the beauty in the dance. And yet the operator dances with the marionettes. For there is something mysterious about the simple curvatures and movements that the puppets follow. Those paths are taken by the soul of the dancer. The operator must transpose himself into the centre of gravity of the marionette. If the operator is able to transpose himself thus, he is in unison with the centre of gravity of each independent movement. Affectation is its obverse, that is to say when the moving force appears at some point other than the centre of gravity of the movement. The weightlessness of the puppets derives from the fact that they glance lightly at the ground, like elves, and through such momentary checks, renew the swing of their limbs. We humans must have it to rest on, to recover from the effort of the dance. Otherwise, we remain what we are: isolated, self-conscious and all too human! Only God can equal inanimate objects in grace, concludes Von Kleist. Grace appears only in that human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness; that is, in the puppet or in the God.

This transposition, the recovering of wonder and weightlessness in movement and curvature is also a turn. A turn towards an event. The turn towards an artistic event means having a perception of a relationship between the name and the thing. It is to this relationship that Blaise Pascal has given the name of time. We turn towards the same entity when we say time, a harking towards a certain kind of congealed sensibility. Art deals in such a tropological timefor trope literally means turn. This idea of troping may sometimes contract into pure sign too. At those moments art does not need any detourit simply says whatever is. J. Hillis Miller calls this investment in tropes and signs a certain kind of catachresis. We cannot verify the unknowable time of wonder but we sure can feel the unknown and the unsaid in our guts, running in our bloodstream. Literature is a vector, a directional motion towards such a time that is eerie, ominous and enchanted.

How can literature catch a sense of lived time and how can time elicit from us, the producers and connoisseurs, a specific sense of artistic consciousness? Here is Paul Valery: I catch the word time as it flies by. This word was absolutely limpid, precise, honest, and faithful in its service, as long as it played its part in a proposition, and as long as it was spoken by someone who wanted to say something. But here it is, all by itself, seized by its wings. It takes revenge. It makes us believe that it has more meaning than it has functions. It was only a means, and now it has become an end. It has become the object of a frightful philosophical desire. It changes itself into enigma, into abyss, into torment of thought (Valery, 2003). The essays here are largely concerned with time as this idea of an enigma, which urges us to deploy the figurative language of a certain kind that takes us closer to the