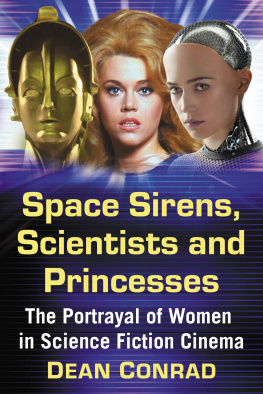

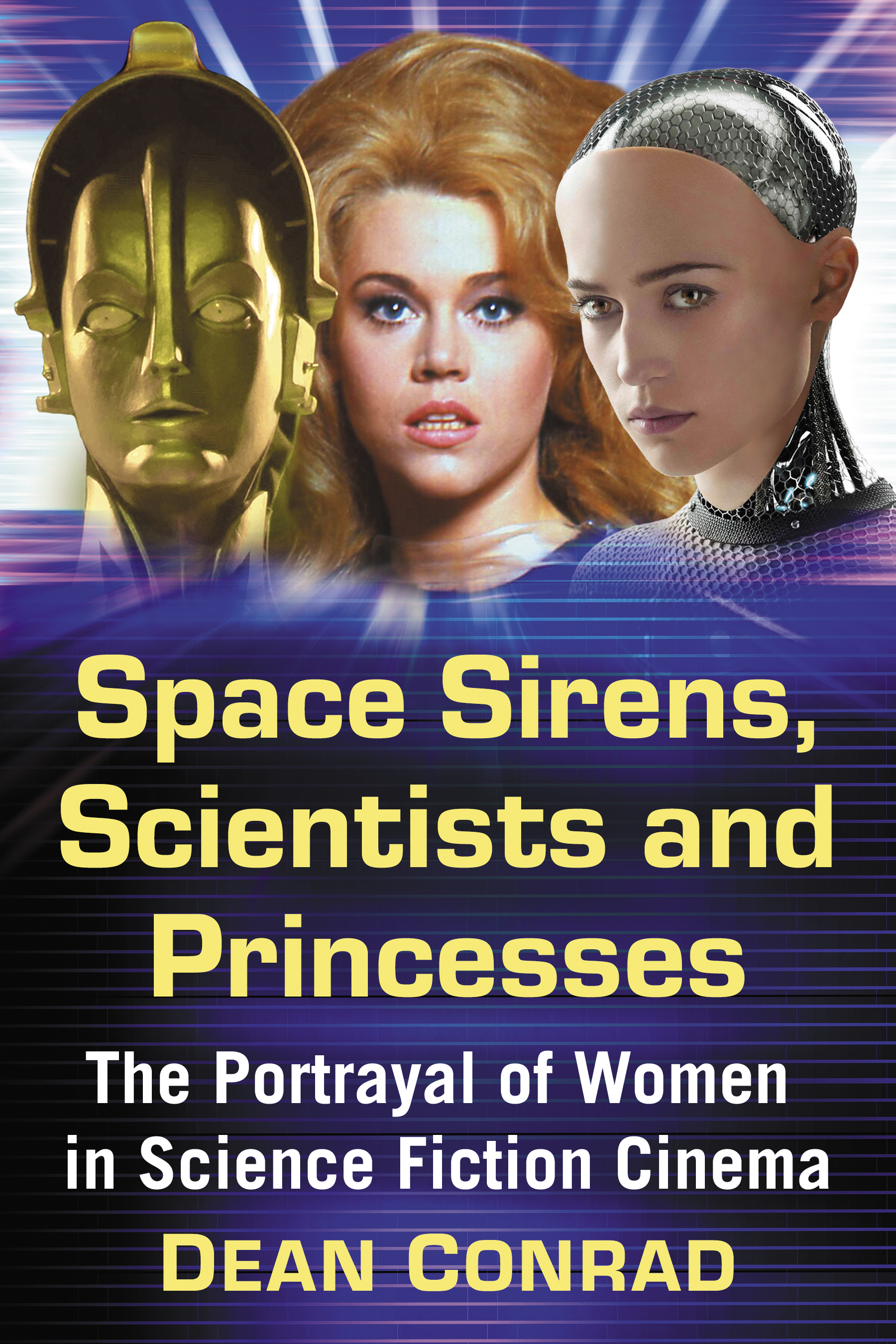

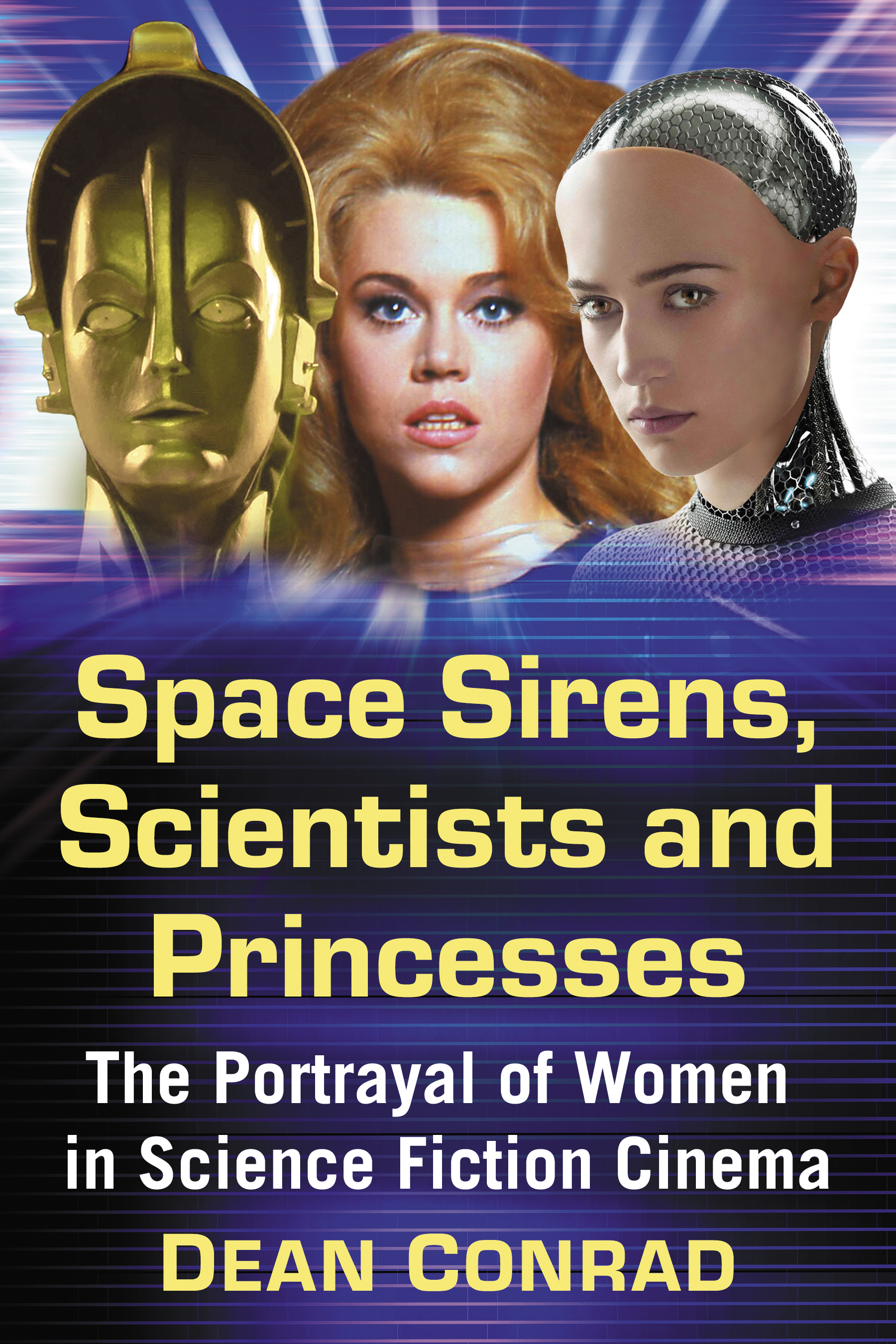

Space Sirens, Scientists and Princesses

The Portrayal of Women in Science Fiction Cinema

DEAN CONRAD

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3271-1

2018 Dean Conrad. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: (left to right) A replica of the Maria robot from the 1927 film Metropolis (Science Museum, London); Jane Fonda as the title character from the 1968 film Barbarella (Paramount Pictures/Photofest); Alicia Vikander as Ava from the 2015 film Ex Machina (Universal Pictures/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Lynne, with love.

Im sorry I couldnt include

This Is Spinal Tap. Maybe next time.

xxx

Acknowledgments

Back in 1993, my dear friend Tim Hatcher bought me my first laptop computer, so that I could write my first book during my year away in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was quite a machine: chunky and heavy, with a monochrome display and a 100-megabyte hard drive. Tim considered it a gift, but I intended to reimburse him from of the proceeds of that book. As it turns out, he was closer to the truth. Again. It is the unerring support and the regular acts of kindness, generosity and forgiveness of friends and family over many years that have enabled me to continue doing what I do. They should be recognized here, so my heartfelt thanks go to Mum and Dave, Jim and Gillie, Sarah and Roy, Irene and Barry, Chris and Louise, Geography Tim, Theatre Tim and of course Lynne. Always there when I need them.

Special thanks specific to this book must start with Lynne; I couldnt have done it, or many other things, without her sacrifice and support. John Streets trawled through every page of the manuscript, except this one, and kept me supplied with feedback and interesting snippets from the daily newspapers. I am grateful for his sterling efforts (although I must confess that I didnt always get around to reading the cricket reports). Thanks also to Jason Gould for his supportive and incisive comments, especially on the early chapters; they have been greatly appreciated. My friend and Japanese teacher Sayuri-san kept me sane with nonscience fiction conversation during the bulk of the writing, so to her I say,

Additional thanks are due to those scholars, critics and commentators who have responded to my e-mailed requests and questions. Most of them have been quoted and referenced in the main text in some way; all of them contributed more than I have had space to include. For their time, support and generous spirit, my appreciation goes to John Clute, Christine Cornea, Glen Donnar, Matthew Wilhelm Kapell, Jane Killick, Marie Lathers, Penny Montalvan, Lynne Magowan, Laura Mulvey, Bonnie Noonan, Simone Odino, Ace G. Pilkington, Olga A. Pilkington and Jay (J.P.) Telotte.

Finally, I would like to recognize John Wesley Harris, whose death in 2008 robbed me of a mentor, an advocate and a friend. All those trips to the cinema were not entirely wasted, John!

Preface

Invisible Man

This book has been busting to get out of me since I completed my Ph.D. on the subject almost 20 years ago. Back then, the publishers that I contacted didnt seem to want to take women in science fiction films seriouslyor at least not my thoughts on them. Populist imprints saw the work as too academic, while university presses were not convinced that it was academic enough. Twenty years on, the landscape of genre cinema study has changed, as the field of cultural studies has blossomedespecially in the U.S. However, prejudices and detractors remain. My recent attempts to develop a television documentary series exploring this subject were met time and again with the same response from broadcast commissioners and editors: Its too niche. By which they must mean that the representation of roughly half the population within the most popular cinema genre of the day is too niche. The battle for credibility is not over.

But prejudice cuts all ways. I have one acquaintancea lifelong science fiction literature readerwho continues to scoff at the idea that the genres movie output might merit any serious analysis or discussion. He seems to have forgotten that his favored form has fought hard against negative perceptions created by the pulp novels, magazines and comic books that popularized Scientifiction in the early decades of the 20th century. He may not think that those early forms merit study either; hes certainly unlikely to endorse the popular cultural notion that if anything is worth talking about, then everything is.

While I was researching in 1993/4 for my first attempt at a book, Star Wars: The Genesis of a Legend, I was quizzed by a former school friend, and another detractor: Why are you bothering with that old film? Why arent you writing a book on Jurassic Park? Why indeed? After all, it was clear that Star Wars was going to disappear without a trace. My next detractor appeared in the form of a senior lecturer when I came to select my Ph.D. research topic. Your thesis will have to work extra hard to convince people that this is worthy of a doctorate, he warned. Shakespeare would be an easier sell. The advice was well-intentioned, but it seemed ironic coming from a scholar in the field of drama, a related subject not long out of its own battles for recognition by the academic community. Happily, my enlightened examiners had my back. Professor Neil Sinyard had written a book on Nicolas Roeg (and corrected the misspelling of the film directors name in my thesis) and Professor Edward James was, and remains, a respected science fiction expert. They were rigorous, but ultimately well-selected by my supervisor, the late and much-missed John Harrisfor years my cinema-companion on trips to see the latest science fiction release.

My earliest science fiction cinema memory is of standing in line outside my local ABC in Colchester, England, waiting to see Star Wars. That must have been early 1978, when I was almost eight years old. My next memory is of rushing home to see a documentary about it, broadcast by one of only three television stations that we had in the UK in those days. We had no recording devices, so if a program was missed, it was gone, until the repeat. I remember feeling gloomy at the realization that we would have to wait maybe five years for Star Wars to be shown on television. I had become a fan.

In those days, boys like me didnt really think much about the role of women outside the home environment, much less their representation in science fiction cinema. It must have seemed natural that Princess Leia was a damsel-in-distress, and not unnatural that Aunt Beru was just about the only other woman in the filmand spent most of her time preparing food. Five years and two Star Wars movies later, the situation hadnt changed very much. I had not been old enough to see Alien at the cinema, so I didnt yet realize that women in science fiction films didnt have to lounge around in gold bikinis, waiting to be rescued.

Next page