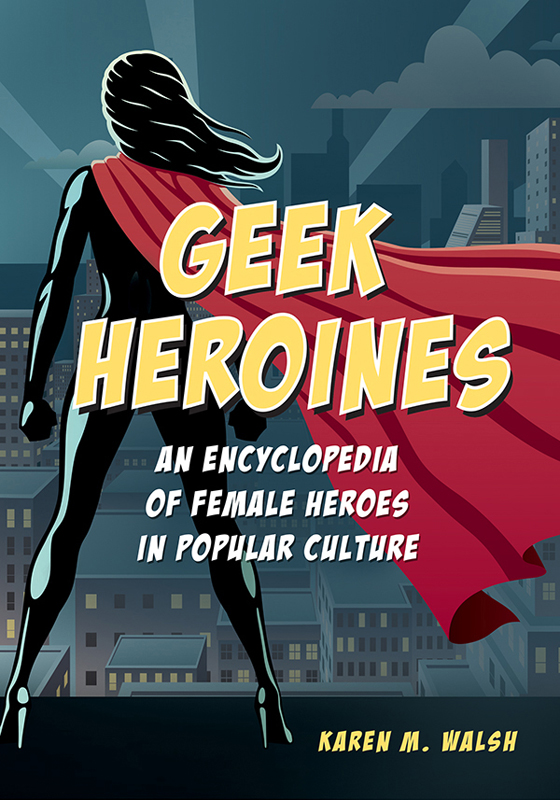

Geek Heroines

Geek Heroines

An Encyclopedia of Female Heroes in Popular Culture

KAREN M. WALSH

Copyright 2019 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Walsh, Karen M., author.

Title: Geek heroines : an encyclopedia of female heroes in popular culture / Karen Walsh.

Description: Santa Barbara : Greenwood, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019014406 (print) | LCCN 2019980386 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440866401 (hardback) | ISBN 9781440866418 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Women heroes in mass media. | Women in popular culture.

Classification: LCC P94.5.W65 W34 2019 (print) | LCC P94.5.W65 (ebook) | DDC 302.23082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019014406

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980386

ISBN: 978-1-4408-6640-1 (print)

978-1-4408-6641-8 (ebook)

232221201912345

This book is also available as an eBook.

Greenwood

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

147 Castilian Drive

Santa Barbara, California 93117

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

To anyone who ever felt they couldnt find a geek superheroine who matched their own identitywhether because of race, disability, gender identity, or other reasonthis book is to inspire you to find your own inner, geeky superheroine.

Contents

To my GeekFamilyNetwork, especially Corinna Lawson, A. J. OConnell, and Anika Dane, without whom I would never have been able to become a geek writer. With special thanks to Jules Sherred for teaching me the importance of gender identity to ensure inclusion.

To my kiddo, L, who drives me to be a better person and make sure that the next generation of geeklings is wholly represented in geek culture.

To my partner in Geekdom and life, Dave, without whom our family wouldnt have eaten during the last push toward publishing. Youre my rock, my best friend, and the person who always lets me be myself, no matter how hard that is for you.

Defining Geeks and Nerds

Until recently, the words geek and nerd came with the mainstream nose wrinkle of disgust. Stereotypical depictions of nerds and geeks included high-water pant legs, pocket protectors, broken glasses fixed with masking tape, and socially awkward behavior. In 1989, the ABC television show Family Matters introduced the quintessential geek/nerd stereotype with its character Steve Urkel (Jaleel White). Awkward and often annoying, Urkels well-meaning interruptions acted as comedic relief.

Although many people use the terms nerd and geek interchangeably, the two differ slightly. The term nerd more often refers to someone deeply interested in the academic pursuit underlying a topic. For example, someone might be a word nerd. A word nerd would focus on both the definition and history behind a term. Moreover, most nerds focus on small details within a topic, such as arguing over superhero origin stories. The term geek connotes passion. In his article Geek Policing: Fake Geek Girls and Contested Attention, Joseph Reagle uses J. A. McArthurs definition: To be geek is to be engaged, to be enthralled in a topic, and then to act on that engagement. Geeks come together based on common expertise on a certain topic. These groups may identify themselves as computer geeks, anime geeks, trivia geeks, gamers, hackers, and a number of other specific identifiers (Reagle 2015, 2864). While nerd focuses on the brain, geek focuses on the heart. Geeks love things, and they love them passionately.

Defining Geek Culture

When people hear the term geek culture, they focus on science fiction, comic books, fantasy novels, and video games. In their article A Psychological Exploration of Engagement in Geek Culture, the authors defined geeks as obscure media enthusiast and explained that during the 1980s, increased technology adoption made the marginalized interests more mainstream (McCain, Gentile, and Campbell 2015). Additionally, they create a canonical list of media interests that were geeky began to form, including science-fiction and fantasy, comic books, roleplaying games, costuming, etc. These interests tended to share common themes, such as larger-than-life fantasy worlds (e.g., Tolkiens Middle Earth), characters with extraordinary abilities (e.g., Superman), the use of magic or highly advanced technologies (e.g., futuristic technologies in Star Trek), and elements from history (e.g., renaissance fairs) or foreign cultures (e.g., Japanese cartoons, or anime). Demonstrating knowledge of or devotion to these interests became a form of social currency between self-proclaimed geeks (McCain et al. 2015). Meanwhile, Joseph Reagle defines geek culture using definitions from online tests, such as Podcaster and cartoonist Scott Johnsons (2007) illustration of The 56 Geeks depicts anime, Trek, Jedi, electronics, and cosplay geeks, among many others. Surprisingly, only three of Johnsons fifty-six geeks are unambiguously female: the scrapbook, cosplay, and ren faire (medieval cosplay and reenactment) geeks. Internet humorist Lore Sjberg (2010) attempted to capture relative geekiness within a hierarchy. His diagram showed that science fiction authors consider themselves the least geeky, followed by different types of fans, furries (those who like dressing up as animals), erotic furries, and finally people who write erotic versions of Star Trek where all the characters are furries (Reagle 2015, 2864).

Although this list not definitive, it provides an excellent example of the type of cultural properties that geek culture encompasses.

For a long time, the public felt these cultural items had little value. Science fiction began as early as the late 1800s when books such as Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde attempted to discredit new science. At the time, however, the public considered the novels frivolous and without intellectual merit. As syndicated popular literature became more common in the early 1900s, science fiction also became serialized in magazines. Many intellectuals viewed serialized popular fiction, which would later be associated with dime store novels and pulp fiction, as lower status. These intricate interconnected social beliefs led to science fiction becoming a counterculture rather than dominant culture.

In the early 1900s, several science fiction magazines began to publish. Hugo Gernsbacks Amazing Stories, however, established a letters-to-the-editor column that included fan addresses. As people reading this niche magazine began to write to one another, they created the first fandom. Additionally, as comic books became more prevalent in the 1940s and 1950s, they also began incorporating a letters-to-the-editor columns. Through these letters, fans could connect socially with others who share similar interests. This ability to share a passion across a large distance became a hallmark of geek culture which continues today via the internet.