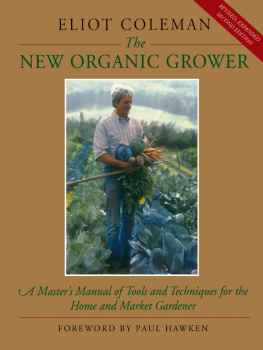

THE NEW ORGANIC GROWER

THE NEW ORGANIC GROWER

A Masters Manual of Tools and Techniques for the

Home and Market Gardener

REVISED AND EXPANDED EDITION

ELIOT COLEMAN

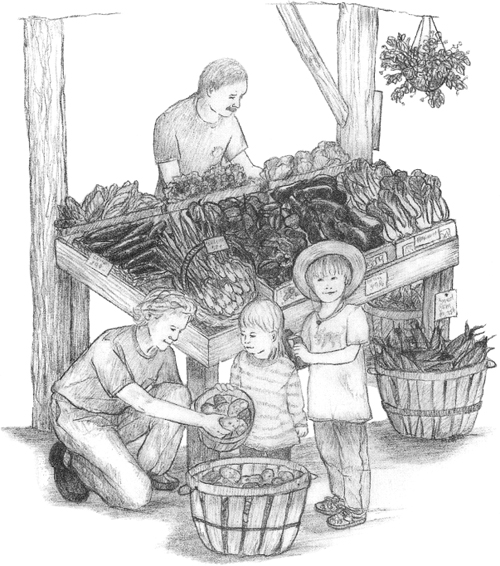

Illustrations by

Molly Cook Field and Sheri Amsel

CHELSEA GREEN PUBLISHING COMPANY

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION, VERMONT

Copyright 1989, 1995 by Eliot Coleman

Except where noted below, illustrations copyright 1995 by Molly Cook Field

Illustrations on the following pages are copyright 1989 by Sheri Amsel

8, 11, 17, 30, 35, 37, 64, 51 (both), 52, 56, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 66, 70, 74 (both), 75

(both), 8081, 103, 106, 109, 110, 119, 128, 129, 131, 134, 135, 137, 140, 143, 144, 145,

146 (lower), 148, 151, 160, 161, 164, 169, 172, 175, 176, 180, 187, 194, 197, 210, 212

(lower), 213 (both), 214, 217, 219, 220, 268, 273, 276, 296, 298 (both), 300 (both), 301,

302, 303, 304 (both), 305, 306 (both), 307 (both), 308, 309, 310, 311, 312

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form by any

means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

First printing, 1995

9 06

Designed by Ann Aspell

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coleman, Eliot, 1938

The new organic grower : a masters manual of tools and techniques

for the home and market gardener / Eliot Coleman. Rev. and

expanded ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. 326) and index.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60358-014-4

1. Vegetable gardening. 2. Organic gardening. 3. Truck farming.

4. Organic farming. I. Title.

SB324.3.C65 1995

635.0484dc20 9524528

Chelsea Green Publishing

P.O. Box 428

White River Junction, VT 05001

(800) 6394099

www.chelseagreen.com

To SN and HKN

with thanks

One of the intangible legacies the Shakers left to the world is their demonstration that it is possible for man to create the environment and the way of life he wants, if he wants it enough. Man can choose.

The Shakers were practical idealists. They did not dream vaguely of conditions they would like to see realized; they went to work to make these conditions an actuality. They wasted no time in raging against competitive society, or in complaining bitterly that they had no power to change it; instead they built a domain of their own, where they could arrange their lives to their liking.

Marguerite Fellows Melcher

The Shaker Venture

CONTENTS

AS AN AVID READER OF BOOKS ON GARDENING AND AGRICULTURE, I AM convinced that virtually everything intelligent that can be said and written about the subject exists already, almost certainly in English. From Fukuoka to Jekyll, from Thoreau to Berry, from Rodale to Jeavons, all aspects of these earthly crafts that coax life from dirt have been thoroughly detailed for new or seasoned practitioners. And yet when asked to write this foreword to Eliot Colemans book on gardening, I agreed immediately because, in this instance, the world needs and deserves another book.

A teacher once advised me to read the book that saved me from reading ten others. Farmers of Forty Centuries is such a book; so is Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. There must be dozens of books that are offshoots of these, some without even knowing it. When seeking specific knowledge of soil and plant, it can be fairly said that most of the literature one reads is derivative and borrowed. With Eliots book, this is not the case. Eliot is committing himself to print after three decades of intensive work in field and garden, work which has produced spectacular results not only in yield and bounty but in thought and insight. Simply stated, I know of no other person (what shall we call himfield gardener, truck farmer?) who can produce better results on the land with an economy of effort and means. He has transformed gardening from a task to a craft, and finally to what Stewart Brand would call local science.

As I write, the anniversary of Rachel Carsons Silent Spring is once again being celebrated in the media. This is a timely subject, to be sure, but also one of perennial concern in these days of factory farming and its attendant poisons. Yet Carsons classic warning is not merely an echo, for every time the awareness of manmade toxins in our food arises, the lines at farm stands and organic food stores get a bit longer. There is, here and abroad, a slow, incremental, but ineluctable movement toward food that nourishes both person and place, that is grown with a far richer knowledge and awareness of biology than can be found in the 5-gallon cans of chlorinated hydrocarbons provided by Shell or Uniroyal. If the problems of modern agriculture are centralization, simplification, and biological reductionism, then the answers include diversity, complexity, and local knowledge. Such intelligence cannot be obtained in most of our land grant universities, and it is a pity this is so. For while we are justifiably confident that, when it comes to anthropology, physics, and biogenetics, our universities uphold the highest standards of inquiry and experimentation, it is in the area of our land and food where they have failed us utterly. Here we must look to the land itself, and in particular to those people who husband it to find standards of truth that we can live by and that allow us to live in turn.

It is satisfying and tempting to think that the major problems of our day have major answers, but I doubt it. The problems that we faceeroded lands, vanishing topsoil, genetic loss, toxic food, poisoned wellswere created by the temptation to find simple solutions. The answers reside in intimate knowledge of species, biota, soil, climate, and place, a type of observation that is embodied before it is taught or transmitted. Eliot not only embodies this intimate science of place, but has been throughout his life the untrammeled observer, unfazed by theories of any one school of thought, enamored of experience. It is this seasoned knowing that he shares here.

It was Hans Jenny, a soil scientist, who first pointed out that there is often more life below and within the soil than there is above it, including Homo sapiens. This inversion of soil as medium to soil as life itself should be enough to convince any agri-scientist to adopt only those means of agriculture that support and nurture this life. But that has not been the case. Instead it has been (and will continue to be) the gardeners, truck farmers, and small landholders who recognize this fact and act upon it. Just as those who broke the prairie sod were pioneers, the new pioneers are those who restore native land and soil. As biota leaves the soil, so does life vanish from society and civilization as we know it. The act of learning to garden and farm, so sincere and simple on its face, is in the hands of Eliot an act of restoration that has implications far beyond one lifetime. It is a practice. And like any practice, it can only be learned through repetition, dedication, and good teaching. This is the good teaching.

Paul Hawken

SMALL FARMS ARE WHERE AGRICULTURAL ADVANCES ARE NURTURED. NEW ideas are conceived every day by the folks who are solving Natures puzzles. Since I turned in the original manuscript for this book six years ago, I have traveled to Europe once again to see what was new there, spent a month with organic growers in Australia, and continued to develop and refine my thinking. I have benefited from the suggestions of those who read the book and wanted more information on certain subjects or wanted data on areas I did not cover. New equipment options are now being imported or manufactured here in the U.S. And in some cases I have finally made up my mind, by acquiring more information, on points where I was ambivalent.

Next page