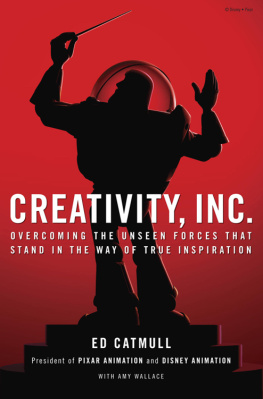

Copyright 2014 by Edwin Catmull

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Catmull, Edwin E.

Creativity, Inc. : overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the way of true inspiration / Ed Catmull with Amy Wallace.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8129-9301-1

eBook ISBN 978-0-679-64450-7

1. Creative ability in business. 2. Corporate culture. 3. Organizational effectiveness. 4. Pixar (Firm) I. Wallace, Amy. II. Title.

HD53.C394 2014

658.40714dc23 2013036026

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design: Andy Dreyfus

Jacket illustration: Disney Pixar

v3.1

For Steve

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: LOST AND FOUND

E very morning, as I walk into Pixar Animation Studiospast the twenty-foot-high sculpture of Luxo Jr., our friendly desk lamp mascot, through the double doors and into a spectacular glass-ceilinged atrium where a man-sized Buzz Lightyear and Woody, made entirely of Lego bricks, stand at attention, up the stairs past sketches and paintings of the characters that have populated our fourteen filmsI am struck by the unique culture that defines this place. Although Ive made this walk thousands of times, it never gets old.

Built on the site of a former cannery, Pixars fifteen-acre campus, just over the Bay Bridge from San Francisco, was designed, inside and out, by Steve Jobs. (Its name, in fact, is The Steve Jobs Building.) It has well-thought-out patterns of entry and egress that encourage people to mingle, meet, and communicate. Outside, there is a soccer field, a volleyball court, a swimming pool, and a six-hundred-seat amphitheater. Sometimes visitors misunderstand the place, thinking its fancy for fancys sake. What they miss is that the unifying idea for this building isnt luxury but community. Steve wanted the building to support our work by enhancing our ability to collaborate.

The animators who work here are free tono, encouraged todecorate their work spaces in whatever style they wish. They spend their days inside pink dollhouses whose ceilings are hung with miniature chandeliers, tiki huts made of real bamboo, and castles whose meticulously painted, fifteen-foot-high styrofoam turrets appear to be carved from stone. Annual company traditions include Pixarpalooza, where our in-house rock bands battle for dominance, shredding their hearts out on stages we erect on our front lawn.

The point is, we value self-expression here. This tends to make a big impression on visitors, who often tell me that the experience of walking into Pixar leaves them feeling a little wistful, like something is missing in their work livesa palpable energy, a feeling of collaboration and unfettered creativity, a sense, not to be corny, of possibility. I respond by telling them that the feeling they are picking up oncall it exuberance or irreverence, even whimsyis integral to our success.

But its not what makes Pixar special.

What makes Pixar special is that we acknowledge we will always have problems, many of them hidden from our view; that we work hard to uncover these problems, even if doing so means making ourselves uncomfortable; and that, when we come across a problem, we marshal all of our energies to solve it. This, more than any elaborate party or turreted workstation, is why I love coming to work in the morning. It is what motivates me and gives me a definite sense of mission.

There was a time, however, when my purpose here felt a lot less clear to me. And it might surprise you when I tell you when.

O n November 22, 1995, Toy Story debuted in Americas theaters and became the largest Thanksgiving opening in history. Critics heralded it as inventive (Time), brilliant and exultantly witty (The New York Times), and visionary (Chicago Sun-Times). To find a movie worthy of comparison, wrote The Washington Post, one had to go back to 1939, to The Wizard of Oz.

The making of Toy Storythe first feature film to be animated entirely on a computerhad required every ounce of our tenacity, artistry, technical wizardry, and endurance. The hundred or so men and women who produced it had weathered countless ups and downs as well as the ever-present, hair-raising knowledge that our survival depended on this 80-minute experiment. For five straight years, wed fought to do Toy Story our way. Wed resisted the advice of Disney executives who believed that since theyd had such success with musicals, we too should fill our movie with songs. Wed rebooted the story completely, more than once, to make sure it rang true. Wed worked nights, weekends, and holidaysmostly without complaint. Despite being novice filmmakers at a fledgling studio in dire financial straits, we had put our faith in a simple idea: If we made something that we wanted to see, others would want to see it, too. For so long, it felt like we had been pushing that rock up the hill, trying to do the impossible. There were plenty of moments when the future of Pixar was in doubt. Now, we were suddenly being held up as an example of what could happen when artists trusted their guts.

Toy Story went on to become the top-grossing film of the year and would earn $358 million worldwide. But it wasnt just the numbers that made us proud; money, after all, is just one measure of a thriving company and usually not the most meaningful one. No, what I found gratifying was what wed created. Review after review focused on the films moving plotline and its rich, three-dimensional charactersonly briefly mentioning, almost as an aside, that it had been made on a computer. While there was much innovation that enabled our work, we had not let the technology overwhelm our real purpose: making a great film.

On a personal level, Toy Story represented the fulfillment of a goal I had pursued for more than two decades and had dreamed about since I was a boy. Growing up in the 1950s, I had yearned to be a Disney animator but had no idea how to go about it. Instinctively, I realize now, I embraced computer graphicsthen a new fieldas a means of pursuing that dream. If I couldnt animate by hand, there had to be another way. In graduate school, Id quietly set a goal of making the first computer-animated feature film, and Id worked tirelessly for twenty years to accomplish it.

Now, the goal that had been a driving force in my life had been reached, and there was an enormous sense of relief and exhilarationat least at first. In the wake of Toy Storys release, we took the company public, raising the kind of money that would ensure our future as an independent production house, and began work on two new feature-length projects, A Bugs Life and Toy Story 2. Everything was going our way, and yet I felt adrift. In fulfilling a goal, I had lost some essential framework.