Dedicated to the belief that, armed

with knowledge, we can coexist with

animal predators on our farms, on

our ranches, in our backyards, and

in the greater world we share.

Contents

Part I

Predators in the Modern World

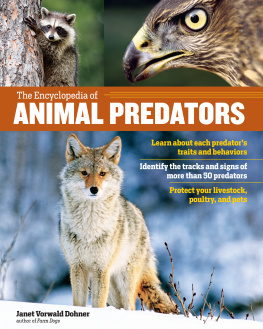

One of the fundamental relationships in nature is that of predator and prey. To feed her fledglings, an eagle swoops with speed and grace to snatch a rabbit on the run. A wolf pack cooperatively chases down an elk, and with that success the whole pack eats. We humans are the ultimate predators, killing both to eat and to survive when threatened by an animal.

In the modern world, many of us are somewhat removed from the predatory act, other than observing a cat catching a mouse. Others of us, however, might walk out in our fields on a beautiful morning to find a gruesomely slaughtered lamb or a pile of decapitated chickens. Even in that moment of great anger and grief, the reality of predator and prey is inescapable and basic. We cant live in a world without predators; therefore, we must learn to coexist with the wild hunters around us while protecting what we raise.

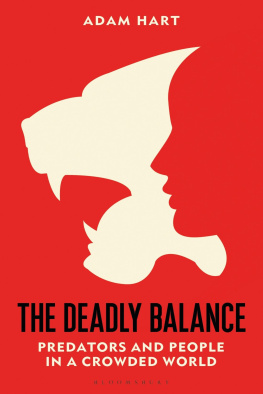

Coexistence

For a long time, humans believed we could exterminate all large predators and shape the earth as we saw fit. We have since found that predators, both large and small, are essential to the healthy functioning of the earths ecosystem. We have learned to appreciate the beauty of wild animals and their lives. Many people now work to save animals threatened with extinction, not only because our world is healthier when it is biologically diverse but also because our lives would be less rich without these animals.

Between the two points of view protecting our domestic animals and valuing nature and all of its inhabitants lies coexistence. Coexistence is possible, and it begins with knowledge. Knowledge of our predators behaviors and habits is essential. Knowledge arms us when we encounter a predator on a walk in the backcountry. With knowledge, we learn how to design and implement predator-friendly systems that protect both our stock and ourselves.

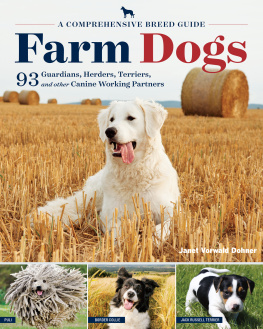

Some of the methods of predator protection are old, as ancient as the shepherd who watched his sheep with his guardian dogs. Others are new, as wildlife biologists help us understand the predators around us rather than succumb to old myths or prejudices. These methods may require as much or more effort than simply eliminating all the predators, but when we value a balanced and sustainable world, they are worth the effort.

Consumers of meat, milk, or eggs can come to value predators and coexistence as well, just as they learn more about the reality of the lives of the farmers and ranchers who provide them with food.

Is not the sky a father and the earth a mother, and are not all living things with feet or wings or roots their children?

Black Elk (Oglala Sioux)

chapter 1

The Predation Situation

When European explorers and colonists arrived in the Americas, the single word they most often used to describe the new world they encountered was abundance an abundance of land, natural resources, and animal life.

Of course, they werent the first to discover the New World, because native peoples had long occupied and used the land, plants, and animals, trading commodities among one another. They altered the landscape, created agricultural fields, burned grasslands and forests to keep them open for grazing for favored herbivores, and may have been responsible for overhunting the megafauna after the last Ice Age.

Following that postIce Age era, some cultures became nomadic hunter-gatherers while others formed permanent communities for fishing or farming. Living more sustainably with nature, native peoples generally met their resource needs without the destruction of diversity and balance that lay on the horizon.

Taming Nature

European settlement would usher in an era of reckless exploitation that, from our contemporary viewpoint, was a truly stunning destruction of wildlife. The Merriams elk, passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, and Labrador duck all went extinct due to relentless hunting. It was an extremely close call for the American bison, reduced from a population of 60 million to just 300 animals by 1900. Herons and egrets died by the thousands, primarily for plumes to decorate ladies hats. Even the white-tailed deer became exceedingly rare in the eastern United States due to human activities. Animals were killed for their fur, hide, or feathers, but none of those was the primary reason that the large predators were destroyed.

The reason was that these animals were regarded as dangerous. As their natural prey was decimated, they became an increasing threat to the colonists livestock. England, Scotland, Ireland, and other European homelands of the colonists had been eradicating wolves and other large predators for centuries. Since these animals were already extinct in the United Kingdom, livestock raisers there had no need to protect their livestock from large or even medium-sized predators. With their only predator being the fox, which was widely hunted on foot and on horseback, sheep were turned loose to graze without active shepherding or livestock guardian dogs (LGDs). There was no tradition of protecting sheep or cattle from serious predation.

It is therefore not surprising that the wolves, bears, and mountain lions of the eastern colonies seemed terrifying. Taming nature was the first order of business. The first wolf bounty was set in 1630 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. From that point forward, the colonies and later the states set bounties for killing the large predators. Thus the hunting, trapping, and poisoning commenced.

By 1870, no mountain lions remained in the eastern states or provinces. By the beginning of the 20th century, wolves were gone from the continental United States and the adjoining areas of Canada except the northernmost Great Lakes region and northern and western Canada. By the 1930s, wolves, mountain lions, and grizzly bears were nearly eliminated from the Intermountain West, except for isolated pockets.

The loss of the large predators and the changing landscape allowed the opportunistic coyote, originally a resident of the Great Plains and arid West, to expand its territory throughout the continent. The widespread coyote is now the single greatest threat to livestock and poultry raisers. The loss of large predators also allowed small predators raccoons, opossums, and skunks to increase in numbers and to expand their ranges as well.

By the 1930s, the three large North American predators wolves, mountain lions, and grizzly bears were nearly eliminated from the continental United States.

Efforts to Coexist

While the destruction proceeded, the foundations of the conservation movement were also being laid. The 19th century saw the origin of a number of progressive movements to abolish slavery, fight for womens rights, establish laws regarding child labor and food and drug safety, and regulate animal welfare. Alongside this progressivism, the love of nature grew. With it came efforts to preserve and protect lands, animals, and natural resources. As the cities became increasingly crowded, people grew to value parks and recreation land for camping, hiking, and bird watching. Sympathy and empathy grew for wild animals.