Table of Contents

List of Tables

Acknowledgments

The author is very thankful for the professionalism and graciousness of many who labor quietly to maintain accurate historical records in national archives and other organizations. These individuals include Janet Delude (Rohna Association), Dori Glaser (Destroyer-Escort Sailors Association), Joel K. Harding (Association of Old Crows), Jonathan D. Jeffrey (Western Kentucky University), David Lincove (Ohio State University), Ed Marolda (recently retired from the U.S. Naval Historical Center), David W. McComb (Destroyer History Foundation), Nate Patch (U.S. National Archives and Records Association), Janice Schulz (Naval Research Laboratory), Katharina Schulz (Archiv Deutsches Museum), David R. Stevenson (American Society of Naval Engineers), and Ron Windebank (HMS Newfoundland Association). The staff at the UK National Archives were extremely skillful and helpful, as was Sebastian Remus, a professional researcher skilled in the ways of the Freiburg-based Bundesarchiv-Militrarchiv.

This research was facilitated greatly by the support and cooperation of other more-accomplished authors in this field, including Ulf Balke, Nick Beale, David Bruhn, Henry L. de Zeng, Jan Drent, Chris Goss, Manfred Griehl, Greg Hunter, Carlton Jackson, Wolfgang-D. Schrer, and Theron P. Snell. Others who maintain an active interest also contributed greatly, including Franck Allegrini, Ed Hart, and Shamus Reddin. Al Penney of the Canadian Navy was especially helpful in sorting out the development of British glide-bomb countermeasures.

The genre of naval and aviation history is well served by amateur and professional researchers who maintain, interpret, and make available data relevant to this story. Many of them are active participants in Internet-based forums that permit easy and effective transmittal of data, insight, and criticism. Two of these forumsWarsailors.com and 12oclockhigh.netwere employed extensively here. Thanks in particular to Brian J. Bines, Hans Houterman, Doug Kasunic, Jerry Proc, and Derek James Sullivan

The author is also grateful to the veterans of this year of warriors and wizards who provided him with their time and insight. This includes several participants in the battles in air and sea: Roy W. Brown (convoy UGS-40), Kenneth C. Garrett (HMCS Algonquin), Russell Heathman (HMCS Matane), Jack Hickman (Operation Dragoon), Ian M. Malcolm (SS Samite), and Charles C. Wales (USS Lansdale). This group includes scientists who fought their own battle over the electromagnetic spectrum: J. T. Doyle (RCN St. Hyacinthe) and William E. W. Howe (Naval Research Laboratory).

Several family members of these warriors contributed to this effort, including K. C. Dochtermann (grandson of Luftwaffe pilot Hans Dochtermann), Chip Gardes (son of USS Herbert C. Jones captain Alfred W. Gardes Jr.), Rick Heathman (son of HMCS Matane crewman Russell Heathman), and Rainer Zantopp (son of Luftwaffe pilot Hans-Joachim Zantopp). Through their efforts I came to know more about the real people involved in this story. Thanks in particular to Chip for tracking down and sharing his fathers personal files and his fascinating life story.

Two noted scholars in the field, Dr. Richard P. Hallion and Norman Polmar, acted as valued mentors to the author and graciously lent him their personal files on this subject that they had each accumulated over the years. Additional valuable assistance during the preparation of the manuscript was received from Anne Doremus, Declan Murphy, and Nic Volpicelli. Editors Adam Kane and Alison Hope were greatly helpful in turning tortured ideas and prose into clear and readable material.

The author is especially grateful to Dr. Allan Steinhardt, a former chief scientist with the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and an expert in radar, radios, and electronic warfare. Dr. Steinhardt, a former colleague of the author, contributed his valuable expertise in analyzing both the Kehl-Strassburg radio-guidance system and the Allied countermeasures. The author would also like to recognize an individual without whom this effort would never have been undertaken: author Rick Atkinson. It was Atkinsons account of German glide bombs in his book The Day of Battle that initiated the authors curiosity and led to this manuscript.

Finally, the author would like to acknowledge the critical role of his wife Maura, without whose friendship, patience, indulgence, encouragement, legal counsel, and constructive criticism he would accomplish little. Thanks!

The author retains responsibility for any mistakes, and that is as it should be.

Introduction

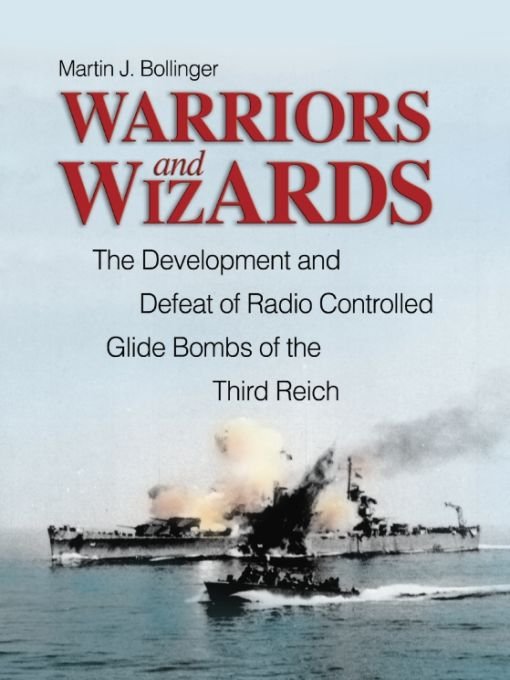

WELLSIAN WEAPONS from MARS

It was not easy in World War II for an aircraft to sink a warship. In our day of brilliant munitions, satellite-based navigation, and weapons calibrated in megatons, such difficulties may be hard to fathom. However, let us take ourselves back to 1943 for a moment and imagine the travails of a military tactician attempting to use an aircraft to destroy invading enemy warships or supply convoys.

First, the weapon of any such aircraft has to be delivered to the target, at a time when that target is typically maneuvering at high speed. A bomb dropped from a great height, say above twenty thousand feet, might take forty seconds or more to fall to the waters surface; in that time, a warship moving twenty-five knots has advanced a half a kilometer (about a third of a mile) from where it was when the bomb was dropped. If nothing else is done to maneuver the bomb, it will miss. Clearly, the pilot can attempt to anticipate the ships motion and adjust the aim, but the fact is that ships have rudders, and those rudders are prone to be employed urgently, heavily, and unpredictably when the ship is taking evasive action.

Air-launched torpedoes are not much better in that the target, assuming it knows it is under attack (hence the value of stealthy submarines over noisy aircraft), inevitably will adjust course in much the same way. Two of the most notable raids in World War II by torpedo bombers against battleshipsby the British at Taranto and by the Japanese at Pearl Harboravoided this difficulty by attacking moored ships or ships at anchor.

One logical response is to engage the target from low altitude and at short distances in order to minimize the time between bomb release and impact. The problem is that aircraft in close proximity to warships, including torpedo bombers, can easily be engaged by the full armament of those warships, making the aircraft especially vulnerable. As pilots were fond of saying, If the ship is within range, so are we.

An alternative, used with impressive results in World War II, is to deploy dive-bombers that approach the target at a high altitude and then drop vertically to the surface, releasing bombs at low altitude then pulling awayassuming they have survived the journey thus far. In this way the pilot can adjust aim until just before the bomb is released. One problem is that these aircraft, and thus their weapons, are necessarily limited in size due to the heavy g-forces encountered in the pull-up. As a result it takes large numbers of them to successfully engage heavily armored targets such as battleships. This fact is well demonstrated by the annihilation of battleships