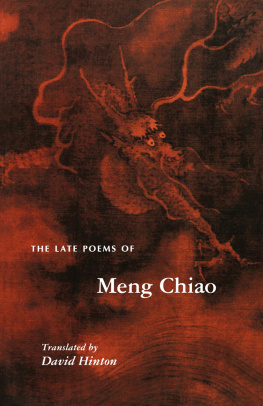

Also by David Hinton

P OETRY

Fossil Sky

T RANSLATIONS

The Analects

Chuang Tzu: The Inner Chapters

Mencius

The Mountain Poems of Meng Hao-jan

The Mountain Poems of Hsieh Ling-yn

The Late Poems of Meng Chiao

The Selected Poems of Li Po

The Selected Poems of Po Ch-i

The Selected Poems of Tao Chien

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu

Tao Te Ching

Introduction and English translation copyright 2002, 2005 by David Hinton

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Book design by David Bullen Design

First published as a cloth edition by Counterpoint in 2002 and as a New Directions Paperbook ( NDP 1009) in 2005.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Penguin Books Canada Limited

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Mountain home: the wilderness poetry of ancient China /

selected and translated by David Hinton.

p. cm.

Originally published: Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 2002.

A new directions book.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8112-1624-1

ISBN 978-0-8112-2442-0 (e-book)

1. Chinese poetryTranslations into English. 2. Nature in literature.

I. Title: Wilderness poetry of ancient China. II. Hinton, David, 1954

PL 2658. E 3 M 65 2005

895.11008036dc22

2005000869

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation

80 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10011

The translation of this book was supported by grants from the

Charles Engelhard Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Introduction

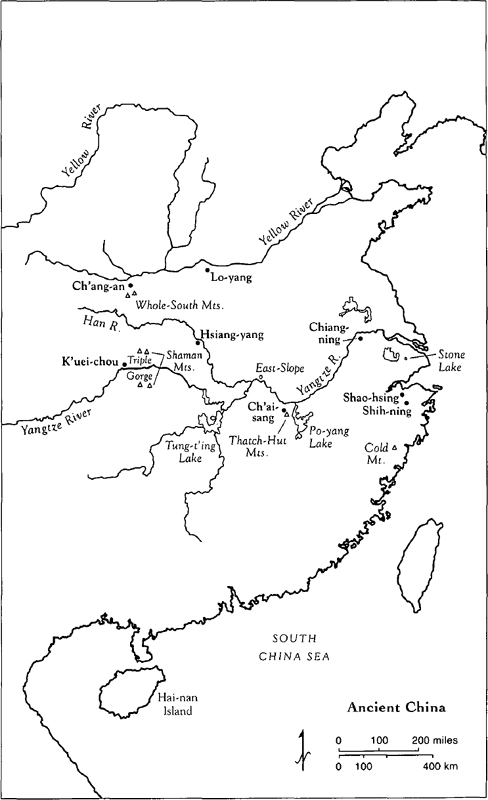

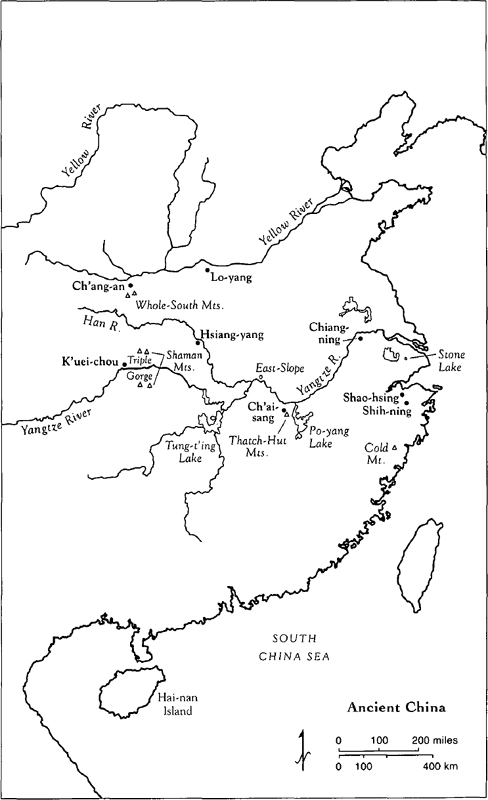

Originating in the early 5th century C.E. and stretching across two millennia, Chinas tradition of rivers-and-mountains (shan-shui) poetry represents the earliest and most extensive literary engagement with wilderness in human history. Fundamentally different from writing that employs the natural world as the stage or materials for human concerns, this poetry articulates a profound and spiritual sense of belonging to a wilderness of truly awesome dimensions. This is not wilderness in the superficial sense of nature or landscape, terms the Western cultural lens has generally applied to this most fundamental aspect of Chinese poetry. Nature calls up a false dichotomy between human and nature, and landscape suggests a picturesque realm seen from a spectators distancebut the Chinese wilderness is nothing less than a dynamic cosmology in which humans participate in the most fundamental way.

The poetry of this wilderness cosmology feels utterly contemporary, and in an age of global ecological disruption and mass extinction, this engagement with wilderness makes it more urgently and universally important by the day. But however contemporary this poetry feels, the cosmology that shapes it is not immediately apparent, as this poem by Chia Tao, fairly representative of the rivers-and-mountains tradition, makes clear:

Evening Landscape, Clearing Snow

Walking-stick in hand, I watch snow clear.

Ten thousand clouds and streams banked up,

woodcutters return to their simple homes,

and soon a cold sun sets among risky peaks.

A wildfire burns among ridgeline grasses.

Scraps of mist rise, born of rock and pine.

On the road back to a mountain monastery,

I hear it struck: that bell of evening skies!

The only tangible indication in this poem that suggests the existence of such a cosmology is the monastery. Given the cultural context, it would probably point a Western reader vaguely toward a Chan (Zen) Buddhist realm of silence and emptiness. The landscape of the poem does indeed seem infused with that silence and emptiness, a hallmark of Chia Taos genius, but the poem offers little more than this. That is, of course, as it should be, for the poem naturally operates in the context of its native cosmology and has no reason to explicate its terms. But for us, those terms must be understood before we can begin to read such a poem at depth.

The poems native cosmology has its source in the originary Taoist masters: Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, who lived in the fourth to sixth centuries B.C.E . The central concept in their cosmology is Tao, or Way. Tao originally meant way, as in pathway or roadway, a meaning it has kept. But Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu redefined it as a spiritual concept by using it to describe the process (hence, a Way) through which all things arise and pass away. We might approach their Way by speaking of it at its deep ontological level, where the distinction between being (yu) and nonbeing (wu) arises. Being can be understood in a fairly straightforward way as the empirical universe, the ten thousand living and nonliving things in constant transformation; and nonbeing as the generative void from which this ever-changing realm of being perpetually arises. Within this framework, Way can be understood as a kind of generative ontological process through which all things arise and pass away as nonbeing burgeons forth into the great transformation of being. This is simply an ontological description of natural process, and it is perhaps most immediately manifest in the seasonal cycle: the emptiness of nonbeing in winter, beings burgeoning forth in spring, the fullness of its flourishing in summer, and its dying back into nonbeing in autumn. In their poems, ancient Chinese poets inevitably locate themselves in this cosmology by referring to the seasonal cyclefor as we will see, deep wisdom in ancient China meant dwelling as an organic part of this ontological process.

The mechanism by which being burgeons forth out of nonbeing is tzu-jan. The literal meaning of tzu-jan is self-ablaze. From this comes self-so or the of-itself, hence spontaneous or natural. But a more revealing translation of tzu-jan might be occurrence appearing of itself, for it is meant to describe the ten thousand things emerging spontaneously from the generative source, each according to its own nature, independent and self-sufficient, each dying and returning into the process of change, only to reappear in another self-generating form. The poetic significance of this cosmology is especially apparent in the following poem, where the term tzu-jan occurs at an archetypal moment in the rivers-and-mountains tradition:

Home Again Among Fields and Gardens

Nothing like all the others, even as a child,

rooted in such love for hills and mountains,

I stumbled into their net of dust, that one

departure a blunder lasting thirteen years.

But a tethered bird longs for its old forest,

and a pond fish its deep waters so now,

my southern outlands cleared, I nurture

simplicity among these fields and gardens,

home again. Ive got nearly two acres here,