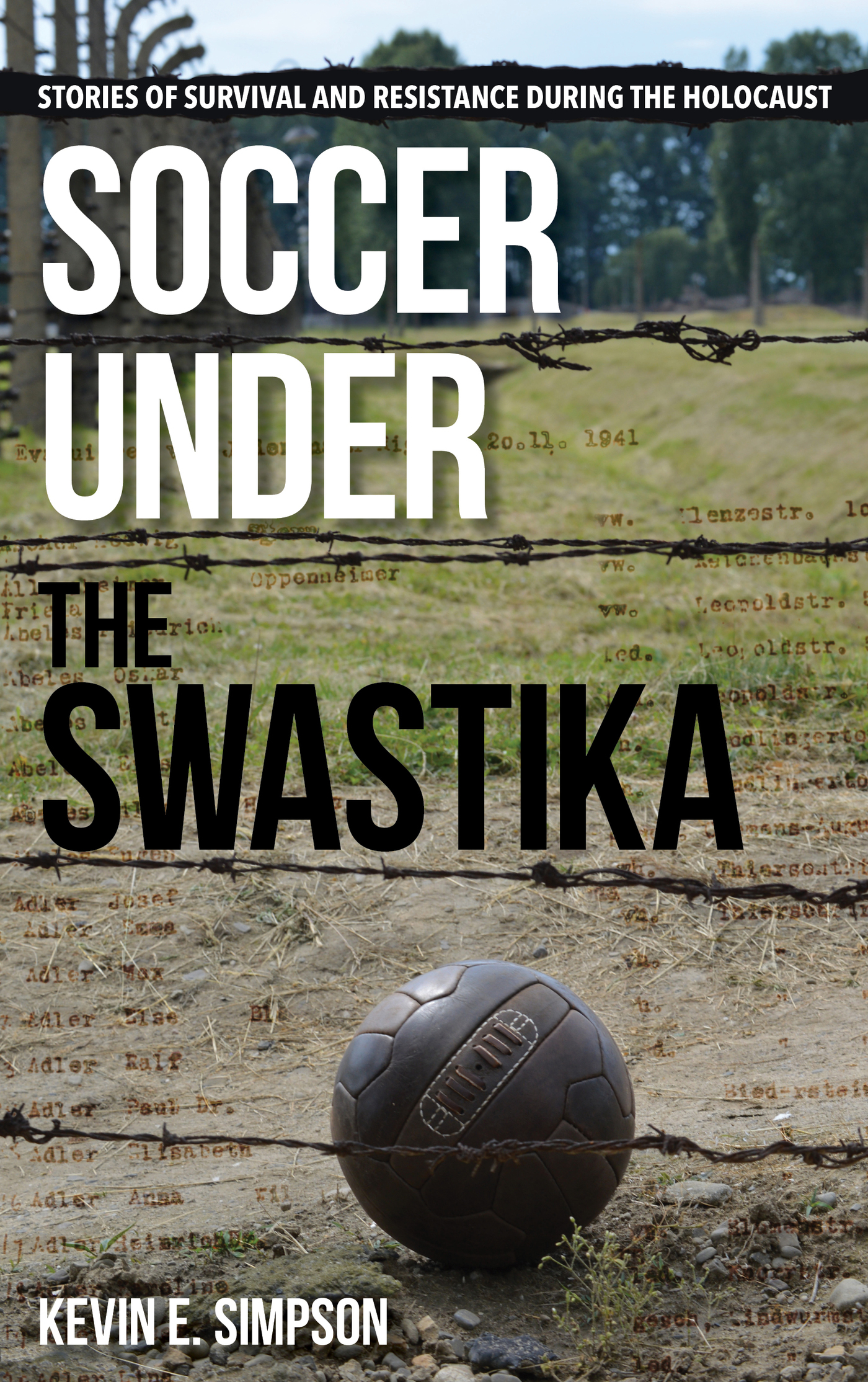

Soccer under the Swastika

Soccer under the Swastika

Stories of Survival and Resistance

during the Holocaust

Kevin E. Simpson

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Simpson, Kevin E.

Title: Soccer under the Swastika : stories of survival and resistance during the Holocaust / Kevin E. Simpson.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016010713 | ISBN 9781442261624 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: SoccerEuropeHistory20th century. | Soccer and warEuropeHistory20th century. | SoccerHistory20th century. | World War, 19391945Occupied territories. | National socialism and soccer. | Holocaust, Jewish (19391945) | Jewish soccer playersHistory20th century. | Soccer playersHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC GV944.E8 S55 2016 | DDC 796.334094dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016010713

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To the memory of Steven Tyrone Johns and

the innumerable voiceless voices lost to the Shoah

Illustrations

Following page 134.

Cartoon postcard from the 1930s featuring a stereotypical Jewish Russian exile as a football being booted from the world. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Wiener Library.

Reichssportfhrer Hans von Tschammer und Osten lecturing Germanys first-ever national team coach Otto Nerz and Fritz Szepan at Berlins Olympic Stadium, 1936. The Granger Collection, New York.

Der Papierene: genius Austrian footballer Matthias Sindelar, 1932. Lothar Ruebelt-Ullstein Bild/The Granger Collection.

A mutually beneficial relationship. Schalke 04 captain Fritz Szepan meeting Der Fhrer at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, October 1937. Heinrich Hoffman-Ullstein Bild/The Granger Collection.

Architect of the BreslauElf and wartime partner Sepp Herberger, who joined the Nazi Party in 1933 but eschewed politics in managing Die Mannschaft for over two decades, 1937. Schirner-Ullstein Bild/The Granger Collection.

Future German national team trainer of the 1974 World Cup champions and international player Helmut Schn in a friendly match against Denmark, a 10 win in Hamburg, 17 November 1940. The Granger Collection, New York.

The best of his generation: Fritz Walter, wearing the German shirt in the final year of international play under the Nazis (1942), would outlast Hitler, going on to captain a resurrected German national side at the Miracle of Berne in 1954. The Granger Collection, New York.

Polish pariah: Volksdeutscher Ernst Willimowski, Silesian-born star for Polish club and national teams, chooses football and identity with the German national team, 1942. The Granger Collection, New York.

The salute. England defeats Nazi Germany, 63, in Berlin in front of 110,000 people on May 14, 1938. The Granger Collection, New York.

Fritz Szepan of FC Schalke 04 scoring the first goal in a 20 win against First Vienna FC to claim the 1942 German domestic championship. The Granger Collection, New York.

Nazi propaganda photos of beleaguered prisoners playing at KZ-Dachau, June 10, 1933. Bundesarchiv, Bild 152-03-13 (top) and Bild 152-03-10 (bottom), photos by Friedrich Franz Bauer.

Sunday-afternoon soccer in the transit camp at Westerbork, Holland, 1943. Leader of the camp Jewish police force looks on. NIOD/Beeldbank.

League football match, started in summer 1943, played on the Westerbork assembly square. Yad Vashem.

Hand-drawn table of Liga Terezn from autumn 1943, author unknown. Champions: Kche (kitchen) team. Pamtnk Terezn, copyright Zuzana Dvokov.

Soccer match in the Poniatowa (Poland) labor camp, circa 19411944. Nearly every prisoner in the camp was eventually murdered. Ghetto Fighters House Museum, Israel.

Handshakes at the start of the Nazi propaganda film Liga Terezn of the September 1, 1944, match featuring Jugendfrsorge (youth welfare) and Kleiderkammer (used clothing) squads. Chronos Media, Germany.

Play during Liga Terezn, September 1, 1944. Chronos Media, Germany.

Corner kick leading to a goal in Liga Terezn, September 1, 1944. Chronos Media, Germany.

Terezn ghetto favorite and former professional Czech goalkeeper Jirka Taussig in Liga Terezn, September 1, 1944. Taussig survived Theresienstadt and later Auschwitz. Chronos Media, Germany.

Souvenir poster from Terezn for team Aeskulap, signed by prisoners. Original color watercolor by W. Thalheimer, 19431944. Pamtnk Terezn, copyright Zuzana Dvokov.

Survivor of the Russian front Herbert Pohl dons the red shirt and black shorts of Dresdner SC in a 40 victory over LSV (Luftwaffe) Hamburg in Berlins Olympic Stadium, June 18, 1944. The Granger Collection, New York.

Austrian civilians conscripted to offer a proper burial to the murdered on the former SS soccer field in the Mauthausen (Austria) concentration camp, May 10, 1945. USHMM, courtesy of Ray Buch.

Matches featuring survivors captivate throngs of fans in Munich after the war. Ghetto Fighters House Museum, Israel; photo by Isak Sutin.

Matches were a popular diversion at the Zeilsheim DP camp (near Frankfurt), circa 19461947. Yad Vashem.

Jewish refugee Aaron Elster, hidden for two years in an attic in Poland, posing in the uniform of his youth team in the Neu Freimann DP camp near Munich, 1946. USHMM.

The rescued making the save for team Hatikvah (The Hope) in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp, the largest in Germany. Yad Vashem.

Inside the fence where a soccer pitch once stood. On the other side, the unloading ramp and the path to death. Auschwitz-Birkenau today, 2015. Courtesy of the author.

Foreword

Simon Kuper

The other day I had lunch with a man in his eighties who had survived the Holocaust. He has never told me much about what he went through, but it clearly continues to shape his view of the world. When he talked about the Syrian refugees now looking for somewhere to live, he reflected, They are just like we were.

This man is one of the last survivors of the death camps. Before long, all direct links with the Holocaust will have died out. I saw the same happen with World War I. When I was a child in London in the 1970s, quite a lot of the old men you saw walking around were veterans of the Great War. Some of them were still known in everyday life as Captain This or Major That. By the time I reached adulthood, there were only a few of them left, mostly mute figures in old peoples homes. In recent years the last few of them have been buried. Today, World War I is effectively dead, like the American Civil War: remembered by history buffs, but only vaguely by the public, and without its former power to influence human behavior today.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.